Chapter 67 – Post-Tama Involvements

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS and FOUR LANGUAGES

1. An IDE (Institute of Developing Economies) Offer

2. The Elite Japanese University Problem

3. The Amateur Columnist and the Yugoslavia Problem

4. The Kiwi Farm

My six years as president at Tama had started to run out. I began to have thoughts of semi-retirement. Sport plus farming and development work in Boso had kept me fit

But I was already well into my sixties and the lecture circuit was running down, at last.

Yasuko had reached retirement age at the Ajiken where we had first met (it is now called IDE or Institute of Developing Economies) and was enjoying her freedom.

She too wanted to spend more time in Japan’s beautiful countryside.

1. An IDE offer

The Institute of Developing Economies (IDE) had asked me to head their MITI-financed school set up to teach the principles of economic development to Japanese and Asian graduates.

It was a mainly titular position, with teaching only if I wished.

On that basis I accepted. Little teaching meant I did not have to get involved greatly in propagating the ideas of Japan’s MITI-related scholars, namely that unlimited free trade was the key to Asian development.

(Free trade would keep the Asian countries tied to Japan as a supplier of materials in exchange for key industrial products. But I believed they needed protectionist policies to be able to produce those industrial products, for themselves at first and later possibly for export.)

But the students were good value. They were up-and-coming young bureaucrats from the Asian countries.

Family responsibilities were also getting lighter. My two sons were at or close to university graduation and finding jobs.

2. The Elite Japanese University Problem

Parents seeking a good future for their children in Japan (myself included) face a cruel dilemma.

Unless their child goes the IT route, the main way for them to gain reasonably easy entry to good employment is for them to graduate from a so-called elite university (there are said to be four of them in Japan).

But in that case you have to force your child to submit to the severe competitive exams needed to get into one of those elite universities.

And sending your child to an elite university does not automatically good education. In fact it can be quite bad.

The elite university has no incentive to offer students good education since the mere fact of those students having graduated from that elite university guarantees them good employment.

For the same reason, the students there also have no incentive to study.

Many parents (like myself) submit to the selfish desire of having one’s child go to an elite university, and hope that somehow the harm from the poor education can be avoided.

…

Both my sons, Dan and Ron, had got into the elitist Keio University, thanks in part to their English language ability (English carries inordinate weight in entrance exams for many universities).

Older son, Dan, had gone the conventional ‘escalator’ route – entry to Keio’s elite secondary school which guaranteed his entry to Keio, where he entered the economics faculty.

There he had discovered just how bad Japan’s elite universities can be, but had held on long enough to graduate. In his own words, his years at Keio had taught him mainly mahjong and fast beer drinking.

For one crucial exam he had been asked to write an essay on Asian economic progress through free trade. I helped him with what I thought was a good basis for an original essay, pointing out how protectionism had also helped some economies at times, Japan especially.

But his teacher like many others at Keio was a market fundamentalist. So young Dan was failed. Worse, he had to repeat the year as a result.

Contradicting your teacher by putting forward your own ideas is one of the greater sins you can commit in Japan’s feudalistic education system. I too was failed presumably.

…

Second son, Ron, had also made things difficult for himself.

Thanks to his English ability, he too had got into a quality secondary school – this one famous for being able to get most of its graduates into one or other of Tokyo’s top four universities, with one third going to Tokyo University.

But that precisely was the problem. For three years the students did nothing but focus on the textbooks that guaranteed success in the entry exams for those top universities.

Young Ron was keen on chemistry. But for two years never once did he get to use the school chemistry laboratory.

Just memorise the chemistry textbooks, he had been told. Laboratory experiments were no use when it came to university entrance exams.

He had also got into trouble when he took a week off to go and work as a volunteer after the Kobe earthquake.

So he decided he did not need that kind of education, and just walked away from the school. Technically, he had joined the growing ranks of Japan’s many jookoo kyohi (dropout) students.

Fortunately, Japan has a system whereby students who do not attend high school can also take a special nationwide exam (daiken) to qualify for university entry. It is a concession to Japan’s growing dropout community.

Working from home he disciplined himself to do the required study, and passed. He was then able to take, and pass, the entrance exams for Keio.

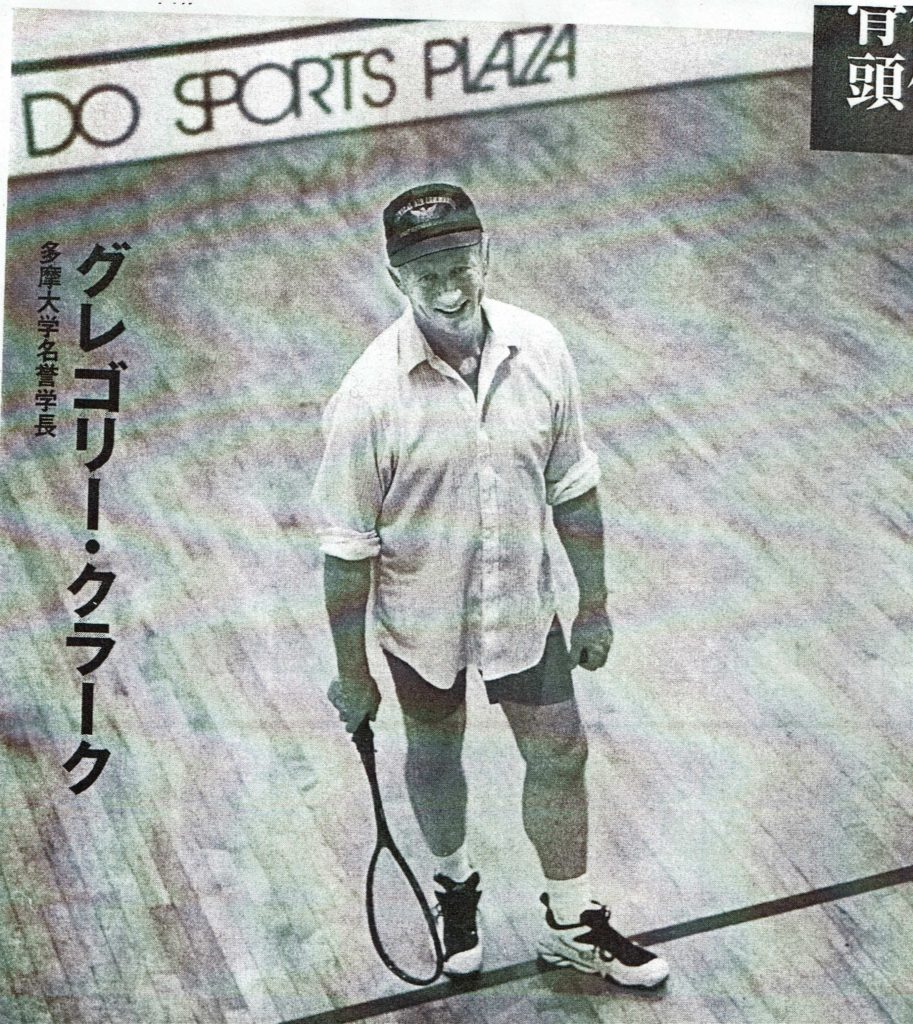

But he too was to be badly disappointed by the flawed education system. So he poured his energies into squash, ending up as one of Japan’s top players competing mainly against full-time squash professionals.

A determined lad, with some of his father’s contrarian instincts perhaps.

Meanwhile I had to consider my own very neglected future. China, as always, was very much on my mind.

But the Chinese diplomats and community in Tokyo played their cards close to the chest.

And the China lobby in Australia were still doing their best to make sure I never got back to China via that route. So maybe I had to look in some other direction.

3. The Amateur Columnist

Having spent years writing for The Australian the temptation to keep writing was strong, even while employed by universities.

First effort was the International Herald Tribute. I had some kind of introduction and ended up talking with a chief editor, John Vinicour.

It was pre-Internet days so copy had to be typed up laboriously and carted down to the central post office in the hope it would appear in the paper two or three days later.

I wrote mainly about Japan, which the paper welcomed. But as the Yugoslavia Wars heated up I could not resist trying to point out the way the West was pushing Serbia into an impossible position.

(I did have some background as a result of the time I had spent in Yugoslavia in 1956, and Moscow 1963-4.)

Even at the distance of Japan I could sense the evil being imposed on the Kosovo Serbs by the US via the likes of Madeline Albright, Hashim Thaçi, and a few other semi war criminals.

NATO unleashed its evil bombing of Serbia.

Fortunately, I was to get the chance to write for the more progressive Japan Times. There I could say what I liked, and get paid for it. Only later did it come into Gaimusho hands.

4. The Kiwi Farm

Meanwhile things had been happening to us in Boso.

For several years we had enjoyed our experiment living deep and primitive in the forests of central Boso. But eventually the transport inconvenience began to weigh in on us.

I began to look for something closer to the ocean and to the railway connections along the east side of Boso.

We ended up with an acre or two of jungle covered terraced land next to a failed early 1970s Tanaka Kakuei-era development.

Once again there were no facilities – water, electricity etc. – but we became friendly with the owner of a hut adjacent to our jungle-clearing efforts and he kindly allowed us to use his primitive rotenburo bath-tub.

But he, like most others in the development, decided eventually to abandon country weekends. He sold us the hut and we finally did have our paradise – water, electricity, and most of all, a roof over our heads.

…

Next came an experiment in serious farming, beginning with some kiwi fruit cuttings on sale at the local farming cooperative.

In the rich jungle loam their rapid growth meant we were soon into the business of using our jungle bamboo to make trellises for the fruit-heavy female vines.

(We chose bamboo rather than metal as part of our effort to stay as native and natural as possible.)

That success led to more plantings, and more kiwis, until eventually we had to organise kiwi picking festivals for friends from Tokyo to get rid of the surplus.

To this day that pagan festival continues, despite the occasional typhoons that knock everything down, and the painful rebuilding efforts that convinced us to use metal rather than bamboo supports for the trellises.

We also decided to house build since we needed something larger than the rotenburo hut to live. It because the Kiwi Farm annex.

We also decided we should invest in some nearby waste hillside land near Nakadaki village as a guarantee against the Bubble land fever that threatened to engulf us.

No one likes to be left behind in a land boom

That emotionally foolish impulse in turn led to the Nakadaki saga, about which more later.