Chapter 66 – The Tama University Experience

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS and FOUR LANGUAGES.

Seeking System Improvements

1. Tama University

2. Motivation in the Classroom?

3. Provisional Entry (Zantei Nyugaku)

4. Other Improvements.

5. Merits of the Zemi (Seminar) System

6. The Successful Graduate School

7. Trying to Repair English Teaching

8. Winding Down

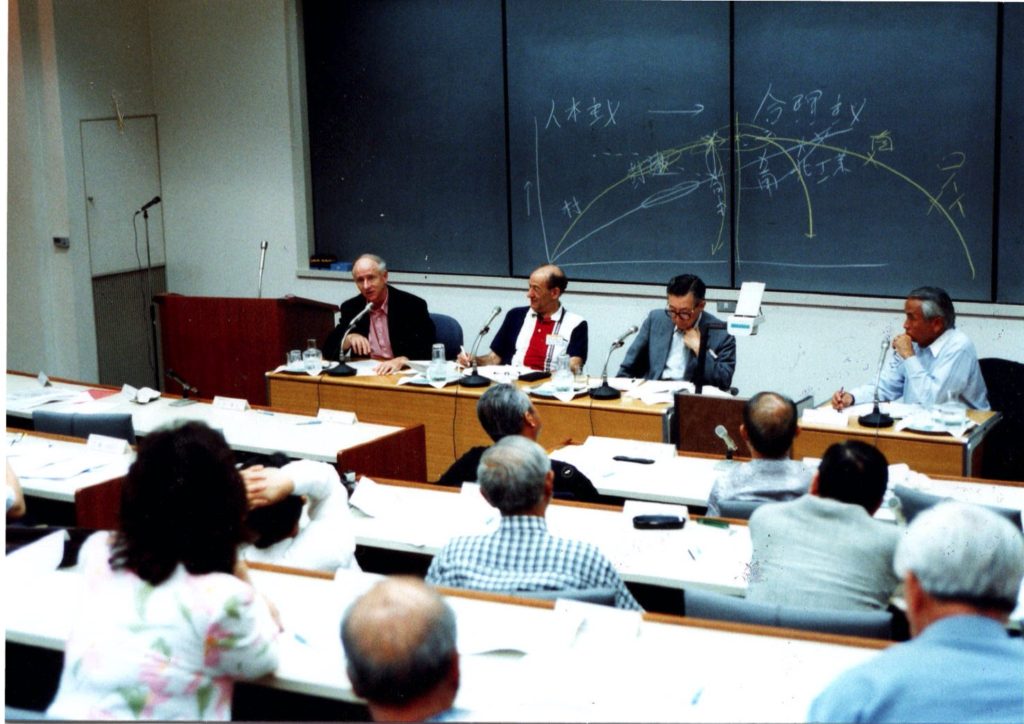

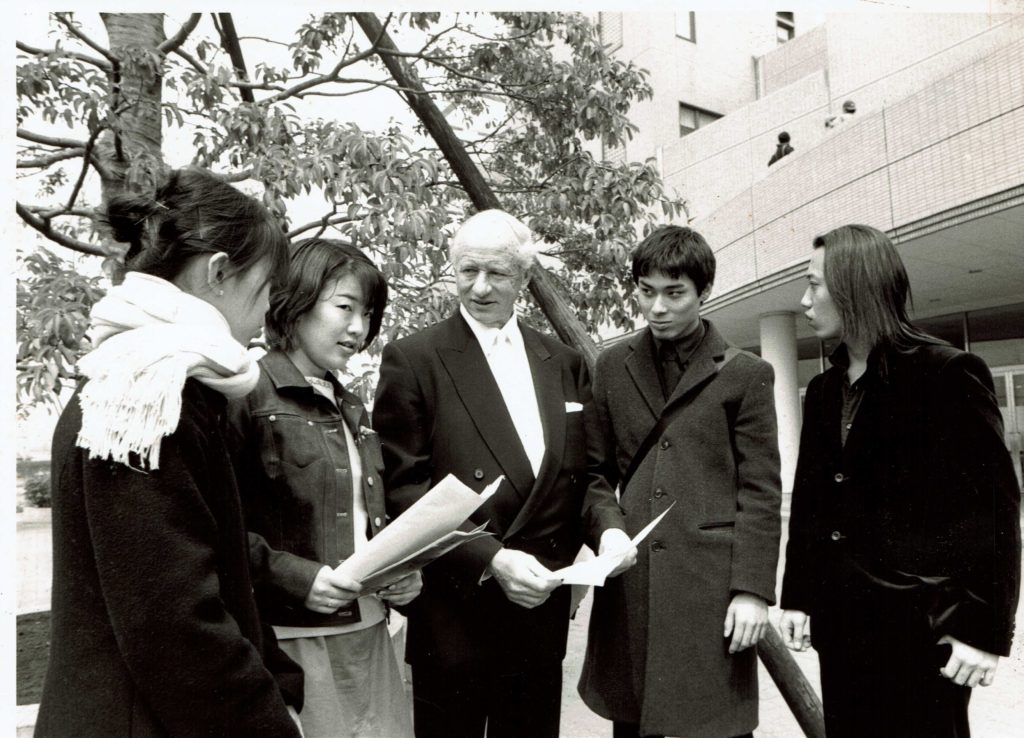

In 1997 I am asked to become president of an all-Japanese university at Tama in the Tokyo western suburbs

1. Tama University

Arriving at Tama I told myself I wanted to find out whether students at an all-Japanese university really were as idle as they were said to be

That turned out to be fairly true.

But I also discovered that when they were doing the things they wanted to do – when they had motivation – they could show extraordinary energy and commitment.

Although the university had only 1,400 students, clubs proliferated like mushrooms.

The annual two-day university festival saw an outburst of energy powered by student intelligence and voluntary labor.

The university drama club gave performances close to professional standard, despite never having the chance to perform before proper audiences.

Indeed long after I left Tama, Yasuko (my wife) would go all the way out to Tama to see their performances.

2. Motivation in the Classroom?

Next move was to see if one could inject some of the same kind of energy and commitment into the classrooms.

But that was not going to be easy.

The entire university system in Japan seems designed to make students, and teachers, feel they exist in what some describe as a nuruma-yu or ‘warm bath’ atmosphere – in a state of soft somnolence.

Failing students, or making them work hard, was seen as unfair and unsporting.

After all, they had paid their university fees. The university was therefore under an obligation to look after them through to graduation, it seemed.

(On one of the many Education Ministry committees I was invited to join I was told that payment of the very high university entrance fee amounted to a contract to provide education through to graduation.

(In theory at least a parent could sue a university if it tried to expel a student for failing grades.

(This was an interesting concept, I thought. How did this mesh with the Ministry’s call for more rigorous grading of students? What happened to those with consistently poor grades?

(Ministry silence.)

True, Tama had better teachers than most.

Many knew the outside business world and had some maturity – something badly lacking in most university people, as I had discovered earlier at Sophia.

Even so, we did have our share of what the students call amai or ‘sweet’ teachers – teachers who make almost no demands on students.

So I decided to try to run a course myself, where there would be demands.

…

First move was to get rid of those term-end exams, where teachers feel obliged to pass almost anyone who shows up.

(I once had a student who would simply write on his exam paper about how much he liked me and how he hoped I would not fail him.)

So I decided that from day one students in my class would have to take weekly short tests (quizzes).

One aim was to do something about those idle students who would just show up for lectures and hope that was enough to gain a pass.

Another was to provide study incentives. Results of the short tests, scored on a scale of zero to ten, would be returned each week.

Only those with a term average of six would pass. A no-show was rated as zero.

Soon the idle ones would realise they were in trouble and leave the course, in time to sign up for classes with one or other of the more amai teachers.

I would be left with the more dedicated students. Or so I hoped.

In particular, I would try to operate on what I see as the only basis for university teaching – require students to read some relevant text in advance of the class and spend class-time answering questions or explaining points of interest.

(That in fact was the basis of the tutorial system I had gone through at Oxford.)

There is very little in the world of undergraduate study that does not have something of quality written about it. Why should teachers waste everyone’s time standing up before the class and just repeating that?

Regular weekly short tests would aim to discover whether students had in fact read the required text in advance of the class.

…

True, having to correct over 100 short test papers each week and hand out results was onerous, especially given the appalling handwriting of most Japanese students, another by-product of the computer age.

But the plan worked out well enough, though hopes other teachers would do as I proved rather optimistic.

3. Provisional Entry (Zantei Nyugaku)

It was at Tama that I developed another idea – one which I thought would not just improve motivation but would also help rid Japan of its ‘exam hell’ for university entry.

I had called it zantei nyugaku, or provisional entry.

Students whose entrance exam grades were close to the pass-fail line, above or below, would be told they could only be accepted on a provisional basis.

If at the end of first year their results were satisfactory, they would be accepted as regular students.

Otherwise they would have to repeat the year, or find themselves another university.

That way we could hope to cut back on some of the rubbish who had just managed to pass the entrance exam, by luck.

…

It would also solve the problem of serious and committed students who due to bad luck or other factors had just missed the entrance exam pass line.

If they really wanted to enter Tama, they would be happy to accept our provisional conditions.

Indeed, some (mainly sons of small company owners whose fathers were desperate to have them trained in business so they could take over as their successors) would be happy to enter Tama under any kind of provisional conditions.

In short, not only was the scheme a way of testing genuine desire to enter Tama.

In effect we would be using end of first year results as a test for marginal students of their suitability for continued university study – certainly a better test of suitability than the standard university entry exams which were simply tests of ability to memorise high school textbooks.

…

But as with many of my other ideas for improving university education, the merits that seemed obvious to me were not so obvious to others.

Over protests I just managed to have the scheme adopted by my university professorial committee.

But it ended up being called doryoku nyugaki (entry through effort) with my original version watered down. (Instead of using the year-end exam, teachers would evaluate the student’s ability by his or her efforts –doryoku– during the year.)

However, and as I mentioned earlier, I did manage to get a mention of it included in the final report of the 1999 Obuchi national education reform commission.

And at the university I was to move to after Tama – Akita International University – it was to be adopted in full, with good results.

At the end of first year the provisionals at Akita often had better results than most of the regulars.

Some teachers also mentioned how the efforts of the provisional students had even motivated regular students to work harder.

…

I should add that there was nothing radical in my ideas.

In most US and Australian public universities, all or most students are zantei nyugaku in the sense that entry to a course of interest is easy for all, but many are weeded out if they fail first or second year-end tests or GPA targets.

Only in Japan could the idea be regarded as dangerously revolutionary.

…

True, the Oxford I knew in the fifties was ‘Japanese’ in the sense that very few of those who managed to pass the difficult entry exams would later be failed.

But we were graded strictly in very comprehensive graduation exams – A, B, C and D.

Those with C or D results found it hard to get good jobs.

(If anyone is interested, I was lucky enough to get a B.)

…

Once when I mentioned this Oxford system to a committee of Japanese businessmen, one said he would prefer the C or D students, provided they had been active in sports.

Their results proved they had not wasted their time listening to useless teachers in meaningless classes!

Out of the mouths of senior Japanese businessmen sometimes comes wisdom, at least where Japanese university education is concerned.

4. Other Improvements?

My six years at Tama passed happily enough (the original four year appointment was extended a further two years).

I too was enjoying the nuruma-yu – in my case freedom from most administrative work. (I was still busy on the lecture circuit.)

Duties were mainly ceremonies (of which there are many at Japanese universities), attending conferences, speeches at various functions.

Each year student quality improved as our graduates moved into the society and became the all-important OBs that every university has to have – former graduates (Old Boys) who help fresh graduates from their former universities into jobs in the firms they themselves have managed to enter.

We also came to be recognised for our efforts, such as they were, to provide education more serious than that in many other similarly ranked universities.

Contrary to appearances, Japanese parents do not like to pay for bad education for their child.

To the extent our claims to provide better education had some publicity, we gained better students.

I came to like many of our teachers, and respect their dedication. Even in a flawed system most mature and responsible Japanese teachers will do their best, even if they can do little to change the system.

5. Merits of the Zemi (Seminar) System

Tama confirmed for me something I had realised earlier when teaching on the Sophia main campus – the merits of Japan’s zemi or seminar system where students are placed in small groups with a teacher of their choice for their third and fourth years to study a particular topic.

The bonding and attention they get does much to solve the motivation problem, and sometimes the job-finding problem.

Later Tama would accept my proposal that zemi systems should be created for second and even first year students.

(First year students have a special need for teacher attention and bonding. I was surprised other universities did not seem to realise this.)

(The zemi was the ideal place to provide that bonding, provided there was some permission to change one’s zemi as one decided later to change one’s teacher or specialised study topic.)

6. The Successful Graduate School

I was also impressed by our still-fledgling graduate school, where some business experience was an entry requirement.

There, we had no problem of motivation. Most were mature students paying the expensive entry fees.

And it was there that the dream of my mentor, Noda Kazuo, was partly realised – the creation of a generation of venture businessmen.

…

Indeed, it was there that I discovered a key element in Japan’s education dilemma.

Most teachers want to teach properly. But faced with students who do not want to study properly they have little incentive to teach properly, which in turn adds to the students not wanting to study properly which in turn…

The key is to find a way to break the vicious cycle. With mature graduate students who realise that their futures depend on their studies the cycle is broken even before it begins.

The problem is the immature under-graduate student.

…

But I would be exaggerating to say I did much for Tama over the six years I was there, other than provide a figure-head, and help get the name of the university into the media. Perhaps my main contribution was imposing a ban on smoking.

7. Trying to Repair English Teaching

Also, in a bid to do something about the harm caused by three years of bad English teaching in high schools, I moved to have English removed from the list of compulsory subjects in our entrance exams. It would be an elective.

My own experience had taught me that when learning a language, if you start in the wrong direction it is very hard to go back and find the right direction later.

In other words, the bad teaching of English in the high schools as preparation for entrance exams did more harm than good.

After university entrance the students who had not taken English for entrance would have to study English for two years, hopefully heading in the right direction.

The move gained great media attention, and great Education Ministry disapproval. Others suggested I had done this as part of the general dumbing down of university entrance exams by universities desperate to attract students.

…

In the end my meddling with the entrance exam system was fairly meaningless since well over 95 percent of students wanting to enter Tama continued to choose English as an entrance exam subject.

They had already endured six years of compulsory English at middle school and were not going easily to look in other directions.

And my teachers of English soon reverted to their favourite teaching techniques – heavy emphasis on translation, grammar and vocabulary.

The one innovation they did accept was an English listening course, with me recording my thoughts about the University and university education generally.

This was popular for a simple reason – listening materials have to based on topics of immediate interest to the student.

But creating a brand new course for students who had only gone up to middle school English was quite beyond the abilities and interests of the staff. My efforts to reform English language teaching in Japan would have to wait till later, if ever.

8. Winding Down

In sum, despite all my lecturing to Japan on the faults of the education system, when given the chance to actually change things I can hardly claim success.

But I did come to know and respect many working the industry. It was not their fault that needed changes could not be made.

I left the university with a large portrait of myself looking over my successors.

The Tamura family which had done so much to create the university and its associated institutions seemed genuine in their statement of seeking to promote liberal values.

But after I left, to help create another new university in Akita, in northern Japan, Tama came to find space for war studies. That was not much in the way of a legacy.

But Tama, like many other universities in Japan, also came to imitate our very successful Akita model, with departments even given the same names as the Akita departments, and students required to study abroad.

Some even sent their management people to visit AIU and produce carbon copies of our systems. So I guess in the end I was to achieve something, even if only indirectly.