Chapter 68 – The Amateur Land Developer

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS and FOUR LANGUAGES.

Learning the Hard Way

1. More Shangrila

2. The Land Boom is Coming

3. I Will Complain

4. The Lockwood House

5.The ‘Freddy’ Factor

6. Becoming a Builder

7. IWNC in trouble

8. Changing Directions

9. More Problems

10. Rural versus Urban Japan

11.The Bankruptcy Factor

12. Financial Speculation

13. Over-Extended

With the lecture circuit still grinding on, I began to realise I had a tax problem. Almost half of everything I was being paid was going to the government.

Fortunately a friendly tax official told me I could save a lot of tax if I incorporated myself. Being incorporated made it easier to claim expenses against income, he said.

(The Japanese tax regime is very generous to small corporations. Too generous. It is a major reason for Japan’s current fiscal problems. )

But first I had to create expenses. That turned out to be very easy, but not quite in the way I intended.

1. More Shangrila

I described earlier the original Shangrila we carved out for ourselves in the early 1980’s near Yoro Keikoku, in the middle of the Boso Peninsula wilderness.

From there in the mid eighties we had moved to yet another piece of abandoned, jungle-covered farm land, near the village of Nakadaki in Ohara town.

And by buying an almost equally abandoned house alongside we gained access to water and electricity. This was a much more liveable than our original Shangrila

Facing due south, the land had been neatly terraced back into the side of a large forested hill, no doubt done by original owners going back centuries.

We were enjoying gratis the fruits of their labor.

With beautiful views over the valley below and without sight or sound of other human beings, often I would just sit there wondering why the 100 million people of Japan were not anxious to join us in seeking out and enjoying these mini-paradises.

There too for several years we had been happy, trekking out from Tokyo every weekend to clear the jungle and grow things, dragging our two small children behind us.

And since kiwi fruit vines grew well in the rich soil and warm climate we soon had a full-scale kiwi fruit plantation producing several thousand fruit a year – much more than we needed for ourselves.

The site became known as the Kiwi Farm.

Photo, kiwi harvest. 13 jpeg

2. The Land Boom is Coming

Sometime in the late eighties someone asked me to buy a scrubby, sugi (cedar) covered, two-acre (2,000 tsubo) hillside in the nearby village of Nakadaki, Misaki town.

I agreed, even though I did not need the extra land. I simply saw it as a cheap insurance against the land boom insanity about to move out of the cities and engulf the countryside.

The speculators seemed poised to buy up every nook and cranny across the nation. So like everyone else, I felt I should get in quickly.

Which is why there was a land boom in the first place, of course.

…

Soon after the purchase I ran into a hail-fellow-well-met Englishman desperately looking for land to run an outdoor training camp for company employees. He would call it ‘I Will Not Complain’.

Could he rent my Nakadaki land? Please!

I felt sorry for him and said yes.

It was, I would realize later, a decision that would change the entire pattern of my life for the next two or more decades.

3. I Will Complain

At first the Englishman had said he just needed the raw land. Clients would sleep in tents, cook over campfires and toilet in the jungle.

But soon the clients began to complain.

So could I install toilets, showers, sleeping quarters, a kitchen, a dining facility…. Please!

It was a tall order. But I could see the chance for tax savings since much of the construction could be expensed. In effect, the Japanese government would be paying for half of everything I built.

But I should have realized that I would be paying the other half, and having to suffer headaches, sleepless nights, and a host of other problems well into the next millennium as a result.

4. The Lockwood House

Problem Number One came quickly.

A New Zealand company called Lockwood had pioneered an unusual technique for building attractive earthquake-proof, pre-fab houses out of carefully dried and laminated radiata pine boards.

I discovered this when a friend with a Lockwood house on the Tokyo outskirts threw a farewell party. He had just sold his land to developers and was leaving Japan quickly, before the tax man could demand a share of his ungainly, land boom, capital gain profits.

I asked what would happen to the house. He said casually the developers would be coming in with machines to crush it into matchsticks, soon.

‘What a waste,’ I said, looking at the solid pine boards and quality fittings.

‘You can have it if you like,’ he replied.

“The boards all slot together like kiddy’s blocks. Just pull them apart and slot them together again and, hey presto, you have a house . “

“And while you are about it you can take the curtains, too, and the furniture, and the knives and forks, and anything else you like. It is all going to be left behind when we head for the airport. We can’t take it with us.”

It was an non-refusable offer. Apart from anything else, I needed some kind of building to house those IWNC clients being made to sleep in the Boso mud.

And as an inveterate scavenger, I am quite unable to pass up anything offered for free.

But inveterate or not, could I pull down an entire house in Yokohama, transport it to Boso, and rebuild it, single-handed?

5. The ‘Freddy’ Factor

At this point, enter ‘Freddy’ (not his real name, though some may be able to guess).

I had run an advertisement to rent the small annex house on the Kiwi Farm. A dark-skinned Texan, possibly half native Indian or Mexican, was the only responder.

‘Call me ‘Freddy’, was his catch-cry.

A former US marine MP, he had stayed on in Japan, trained himself to be a two-by-four carpenter, married a Japanese woman, and then set up his own building company somewhere to the north of Tokyo.

But then disaster. First, the gangsters had got into him on a major project. Then his wife had died, leaving him to raise two children by himself and also leaving him without the crucial Japanese backup for his company (he could not read or write Japanese).

Forced into bankruptcy, he had to try to make a fresh start. (Or so he said.) My cheap rental annex in the countryside would be the start.

…

I had an idea.

The Lockwood house at Yokohama was still sitting on its site, waiting for the wreckers to arrive. Could he pull it apart? Of course, he said, with the assumed confidence I was later to get to know only too well.

Could he put it together again? Again no problem, though he had still to see the house. Would he be happy to do all this while camped out in my small Kiwi Farm annex? Certainly!

At the time it seemed like a marriage made in Heaven.

Or was it Hell?

….

First impression of ‘Freddy’ had been positive. Physically he was very strong.

His spoken Japanese was good. He had learned it entirely through the ear (language teachers around the globe please note).

He had a strong instinctive intelligence. Or at least it seemed that way. Later it turned out that with the intelligence came what the Japanese call warujie (bad intelligence).

Worse, he was also an alcoholic.

I will pass silently over the enormous problems we had getting the Lockwood pulled apart and transported to Chiba. Suffice to say that even though I had given him a contract to do the job I ended up having to do much of it myself, together with the help of Sophia students.

‘Freddy’ simply provided the technology for pulling Lockwood boards apart.

…

I will say even less about the problems we had later. Suffice it to say that at the end of a year ‘Freddy’ was still finding excuses to delay rebuilding the Lockwood.

Meanwhile the Lockwood boards and other materials we had painfully transported all the way from Yokohama were being left outside in the Boso summer heat and humidity, to warp and rot.

I tried to employ him on other tasks, but it was obvious he was simply interested in gaining the maximum money possible for the minimum of work .

Eventually, we had no choice but to part company. He had cost me dearly, and not just in financial terms.

It should have been my first lesson in learning not to take people on trust – not to assume naively that just because you do the right thing for them, they will do the right thing for you.

6. Becoming a Builder

Fortunately I was able to bring up a young carpenter from New Zealand to try to rebuild the Lockwood. Slowly he managed to fit some of the warped planks together.

The final product looked more like a rickety barn than a house. But just for that reason it had great success as a bar.

By this time the Lockwood people in New Zealand were interested in what I was doing. Never before had anyone been able to pull one of their houses apart and rebuild it, they said.

We had made history, of sorts. They set out to encourage me to do more building. The NZ economy was in shambles, the currency had collapsed and the government was going overboard to promote exports.

Lockwood promised to provide materials cheaply, and provide reliable carpenters. I set out to build one or two of their houses, experimentally.

I was hooked on Lockwood’s unusual technology. The finished product was also very attractive – solid boards from floor to rooftop providing a warm and protective feeling.

…

I was also hooked on the simplicity and profitability of the business.

To get a house built all I had to do was ring the company, select a model from their plan book, agree on a price and in a few weeks a container would arrive together with two keen NZ carpenters who would open the container, pull out the pieces, clean up the site and start building the next day.

As soon as they had made some kind of shelter inside the house they would leave the accommodation I had provided, to camp there and be able to start working at crack of dawn right through to sun-set.

(They were in hurry to get back to their women.)

Final product: solid, good-looking, waterproof, and one third the cost of competing US and European kit-home products.

…

OK, but why did I continue? Well, I still had the income from the lecture circuit flowing in every week and had to use it somehow. Why not use it for something literally constructive?

Where-ever I had a piece of flat land I would want to cover it with a Lockwood. Today, years later, they still stand, with hardly a flaw

…

Even so, some queried why an alleged university professor was trying to enter the building business.

I would talk about the need for hands-on experience in running a company – something I was supposed to be teaching as part of a venture business and enterprise management course.

Another reason was a need to find an outlet for mental and physical energy unused in the ivory tower and on the lecture circuit.

Meanwhile another problem, almost on a par with the ‘Freddy’ problem, was slowly developing.

7. IWNC in trouble

IWNC had always had difficulty finding customers – mainly because its ideas of how to run outdoor training courses were weird.

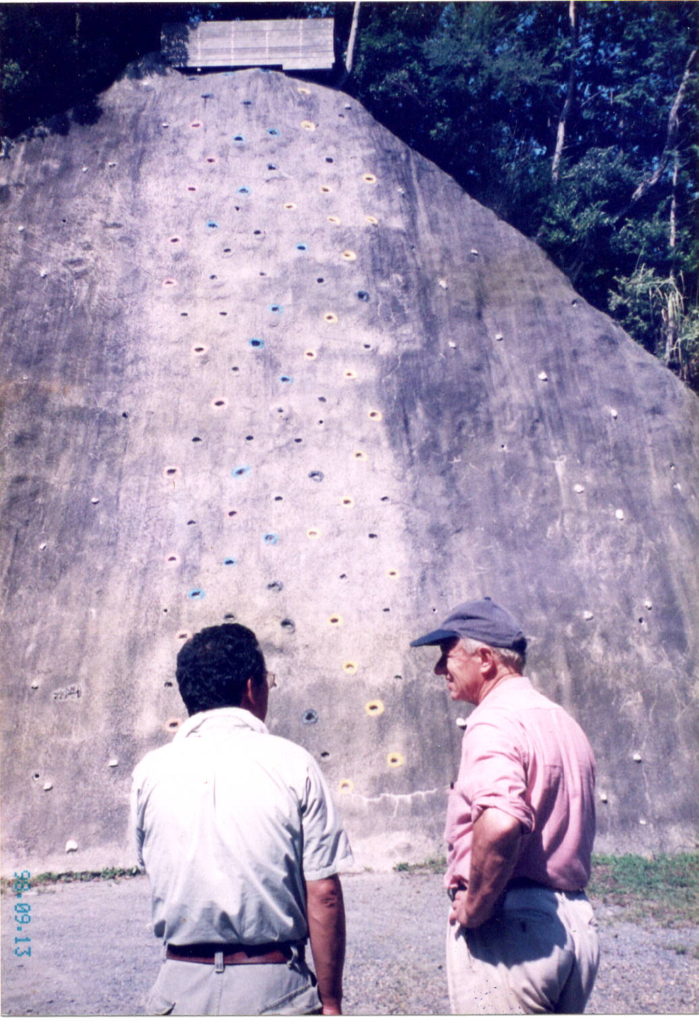

Participants would have to spend hours sitting at the bottom of trees or cliffs, often in the rain, encouraging each other in turn to struggle up to reach the top.

It was supposed to foster group solidarity. But with numbers and complications meaning only one or two climbs per customer per day it was not doing much to foster client solidarity with IWNC. Ominously, they were not getting much repeat business.

I told them about a highly successful, low cost, treasure-hunt style operation in the Hakone forests just outside Tokyo, booked out years in advance (Japanese like challenges where they can all work together in small groups to find a solution).

But the IWNC people were too stuck in their orthodox and very expensive textbook ideas on how to run outdoor training.

Financial controls were lousy too. Money poured out of the operation even faster than rain out of the Boso skies in July.

I invested in the conference room they said they needed – a neat Lockwood construction on the side of a hill.

But IWNC’s order book continued to decline anyway. Eventually the operation was handed over to one of those MBA geniuses whose only concern was the bottom line.

He had little interest in the property I had so carefully built up over the years.

His idea of ‘outdoor training’ was to concentrate on high-paying executives – flying their groups to exotic hotels around Asia where the only hint of the outdoors was a climbing wall at the back of the hotel near the kitchens.

We parted company, and not amicably.

I had to take him to court for unpaid bills.

8. Changing Directions

But with IWNC gone, what was I to do with all the infrastructure I had built for them? One answer was to continue the residential side of the project.

The hillside was already dotted with huts I had built for IWNC, including some rather nice houses I had built for staff.. Why not build a few more houses and I could rent them all out

That way I could hope to get the economies of scale needed to make at least some of the infrastructure worthwhile (by now it included a rather nice tennis court, a canoe centre, and later a squash court made experimentally out of Lockwood timber).

I would try to create a community of hardy souls keen to live in the countryside. Hopefully I would end up with enough rental income to be able to hire a manager.

First move was to build and populate bungalows on adjacent hillsides. Building some more houses on nearby riverside land provided even more scale and population.

I was helped greatly in all this by three young NZ carpenters, arriving one after the other, over a span of almost ten years.

Without them most of the development would have been impossible. Through them I developed a great respect for the Kiwi work ethic.

I also developed a great respect for the Lockwood business ethics and technology.

…

Later I would try bidding for some of the houses thrown onto the local bankruptcy auction market by the Koizumi-induced recession, and renting them out.

I ended up with a ‘community’ of around 50-60 people, mainly foreign but some Japanese, scattered across the hills and plains of mid-eastern Boso.

My aim was to gain the scale needed to make it worth to hire a manager.

Some lived there with their families, commuting in and out of Tokyo daily (the area was only an hour from Tokyo on a fast train). Others came out for weekends and holidays.

To some extent it was a success; income just managed to cover expenses. But managing all the buildings, facilities, repairs, additions, accounts, paperwork etc. was a nightmare.

And while I was able eventually to get myself a good managerial secretary, finding a good site manager was much harder.

One small consolation was that the progressive governor of Chiba Prefecture, Domoto Akiko, came to rent one of my Nakadaki houses.

She would bring out her top officials to see at first hand what she saw as an environment-friendly ‘model’ for developing Chiba’s many unused hillside areas.

(I had to tell her, and them, that ‘nanny state’ restrictions had since made this kind of development almost impossible.)

9. More Problems

One was that in the Nakadaki hill site alone I now had twenty or so houses and bungalows scattered over an area of more than four acres.

They all needed water.

But thanks to Tokyo’s mistaken fiscal policies, the regional authorities had become so starved of funds they could not afford to supply water to new developments, including Nakadaki.

So we had to rely on wells drilled into Boso’s thick sedimentary rocks. We ended up with four of them linked together in a complex network.

Almost invariably they managed to break down when I was not around.

Efforts to educate the Nakadaki population in how to operate the system were only partly successful.

I once found myself stuck at the end of an Internet connection in Peru trying to work out which pump was working and which was not.

My idealistic dreams about creating a community of rugged, independent-minded, outdoor-life loving souls were starting to get ragged.

…

In retrospect, the Nakadaki dream was one of the more foolish things I was to do with my life. I could have completed at least half a dozen research projects and written half a dozen books in the time I had spent fooling around in the Boso forests and mud.

But I did learn something about Japan, hands on.

10. Rural versus Urban Japan

Invited on the lecture circuit to tell foreign audiences how to do business in Japan, I had liked to point out that the Japanese economy was not as nationalistically exclusivist nation as many Westerners believed.

True, its single-minded, group-think mentality had created some areas of the economy where competition was overly intense (kato kyoso in Japanese) and entry difficult.

But the same mentality meant there were other areas untouched and wide open to entry.

The foreigner with a fresh eye could easily discover those overlooked areas, move in, and succeed (as we were to discover during the post-bubble recessions when the foreigners managed to take over much of Japan’s financial industry).

One such area was sensible use of the large areas of unused countryside close to the cities.

In the US and UK, even in Australia, countryside suitable for weekend houses, bungalows or hobby farms within two, even three, hours from the large city centers was greatly sought after.

Sometimes it would sell for almost the same price as outer suburban land. In short, a ratio of one to one.

But in Japan the ratio was almost one hundred to one.

With Japan about to discover the weekend (with government encouragement), inevitably some would want to start using some of this cheap rural land close by.

That at least was my calculation, thanks to my Boso adventures,

As it turned out I was only partly right. Even with the weekend in place the strong Japanese work and socializing ethic kept people in the towns.

Despite much Japanese romantic talk about being their being uniquely sensitive to nature, most were not very interested in countryside to begin with, or at all.

Even Japan’s wealthy have not, for the most part, strongly embraced the idea of having a nice place in the country with a tennis court or swimming pool to which one could invite friends.

Expensive bars and geisha clubs were the places where you did your hospitality.

The development of exclusive residential zones or country clubs in the inexpensive hills, mountains and onsen zones across Japan was virtually completely problem-free. All that was needed was a few foreigners with needed push.

…

Actually, there is one such group that has done this and has done well, thanks in part to management flair combined with foreign flavour. That is Club Med.*

…

(Incidentally, there are few legal barriers to foreigners owning and developing land in Japan.)

(A foreigner I know once registered ownership in the name of a dummy company on the Isle of Man!

(He only got into trouble when he tried to sell it. There had been a slight change in the address of the dummy company and the authorities required massive documentation to prove it was still the same dummy company!)

11.The Bankruptcy Factor

An even greater incentive for my expansionism was the bankruptcy auction system.

The Koizumi-Takenaka recession saw tens of thousands of house owners thrown out of their homes by the banks.

A neat two-story house with a developed garden would be put on the auction-tender block with a reserve price as low as two-three million yen ( 2-3 million USD).

(During the Bubble era frenzy the same banks might have loaned up to twenty million yen with the same property as collateral, telling the owner land prices were bound to double and they should use the money to buy more land.)

Cleaned up and rented out, the return on one of these buys could be as much 10-15 percent, at a time when the cost of housing loans was little over three percent.

That the Japanese were too caught up in their collectivist, doomsday, recession mentality to realize these bargains said volumes about their emotional mentality.

The same Japanese during the Bubble period frenzy had been willing to pay 8-9 percent interest for money to invest in bloatedly-priced real estate now returning only around 3 percent, which was, of course, a major reason why so many of them were going bankrupt.

12. Financial Speculation

Yet another incentive for all this activity was a money-making speculation machine.

One needed only to realize that the mistaken supply-side, fiscal-restraint policies of first the Hashimoto (1996-98) and then the Koizumi (2001-06) administrations would keep interest rates low and the yen cheap for a very long time.

All one had to do to make money was to park one’s funds in Euro and US dollar bonds returning six to nine percent, and use them as collateral to borrow yen from banks at well below one percent (the banks were getting their money at zero percent).

There were also exchange profits as the Euro and USD appreciated against a yen weakened by those mistaken policies.

This very attractive arbitrage situation continued for the best part of ten years. It was enough to keep me in poker chips for quite a while.

It also encouraged me into even more land buying and development without fear of being financially over-extended.

13. Over-Extended

But I was to be badly over-extended in other directions.

The lecture circuit remained busy. I was still running around from one end of the country to the other trying to tell audiences the reasons for the quite unnecessary recession they were being made to suffer.

Government and other committee work continued. So I was still having to spend hours every week in stuffy offices listening to endless reports and empty debates (I justified it to myself by saying I was getting an inside view of Japan Inc. in action. Oh yes?).

My university commitments were to continue for much longer than I had expected.

All this plus the never-ending trips to Boso to watch over various projects meant I was giving far too little attention to other things more important – family, writing, reading, research, improving my Japanese, enjoying my other languages, overseas travel, friends.

But more on that to come.