Chapter 47 – Book Aftermath

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS and FOUR LANGUAGES.

The Talking Monkey

1.The Japanese Lecture Circuit

2.Organising a Lecture

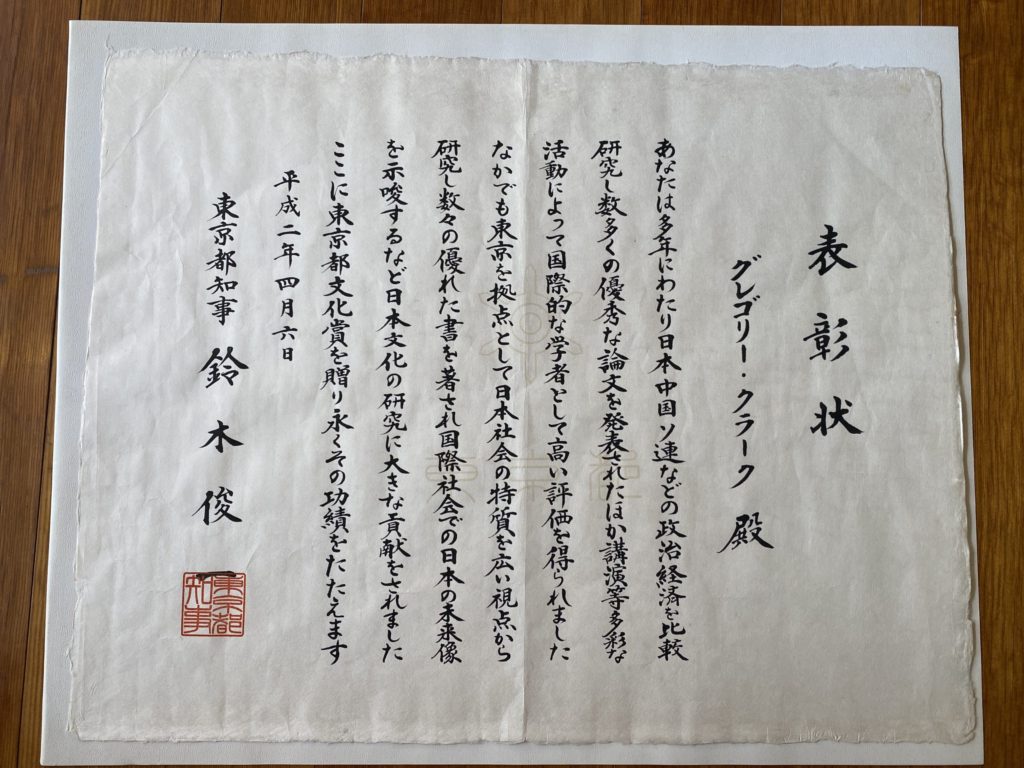

3.Rewards

When I published the Japan as a Tribe book, I had assumed that the only material returns would be royalties from the publisher, Simul.

But if I had known about the rewards from Japan’s lecture circuit I would never have bothered about royalties.

The circuit was to be a source of seemingly endless returns.

1. The Japanese Lecture Circuit

Japan’s lecture circuit was gargantuan.

Many major organizations in Japan – banks and securities companies especially – had branches around Japan.

And in those Bubble years just about every major branch had to be supplied, often monthly, with lecturers for the regular enlightenment or entertainment of their clients.

As well, there were the anniversary parties, annual general meetings and other ceremonies all requiring lectures and lecturers.

Lecturers were chosen mainly for name value. And name value was something I was rapidly acquiring, thanks to those TV appearances.

And if I say so myself I also had what in those days was seen as a rather attractive CV.

The invitations to give lectures soon became a deluge.

Learning to Lecture

My first effort was horrible.

I had been asked by the Kyodo news agency to talk to an audience of several hundred in Nagasaki.

Together with Jiji, the other main domestic news-agency and which has shibu (study groups) all around Japan, Kyodo was to be a major source of lecture requests for a while

The Nagasaki audience was tolerant enough as I stumbled through some badly-prepared notes. I was trying to explain the complicated thinking behind my ‘tribe’ theory, and it was pretty clear the audience had no idea of what I was talking about.

But Kyodo was tolerant enough to give me more lecture requests.

Requests from other sources began to emerge. Eventually they were to come in almost daily.

Life degenerated into a whirlwind of dates, times and places.

…

Family life suffered. Almost daily, it seemed, I would have to leave the family hearth and head off to catch a plane or train to yet another distant lecture site.

A day I remember well began in Hokkaido with a morning session for local businessmen, then by plane to Osaka to talk to a group of foreign investors in Kyoto, and then to Tokyo by bullet train for yet another talk in the evening, this time to an international school.

When you are on the lecture circuit you feel you are propelled by some force which exhausts itself only after you seem to have visited every town and village in the nation.

An average sized city like Sendai I was to visit at least twenty times over the next 25 years.

In Osaka I must have given close to one hundred lectures, in Fukuoka and Sapporo around fifty, and so on.

The topics were varied – the state of the economy, the politics, the education system, Japan’s kokusai-ka -internationalisation- efforts (a favourite at the time), how we foreigners see Japan (another favourite), and of course the subject of the book – what the claim of Japanese ‘uniqueness’ was all about.

Usually I could rely on my ‘instinctive-emotional’ versus ‘rationalistic-ideological’ theory for background. It explained a lot about Japan – the strength of the economy, the weakness of the foreign policy, the confusion in the education system, and so on.

Audiences seemed to like it too. I was able to balance criticisms with what I saw as merits of the Japanese system.

It was a change from the usual boilerplate served up at these talkfests.

Often at the end of the lecture I would be thanked for having given a ‘mimi no itai’ (‘criticising’, or literally ‘ear-hurting’) talk.

Years later I kept running into people who were almost proud of the number of times they had heard ‘the lecture.’

As with kabuki, Japanese audiences do not seem to mind repetition. They get pleasure from slight differences in the performance each time.

…

In my case there was also the talking dog factor.

Why did people pay to come to hear the talking dog? Answer: Not because of anything that the dog had to say, but because the dog could talk.

A foreigner talking about Japan, in Japanese, was, in those days, something of a rarity.

In the years since the book was published I must have given well over 2,500 lectures.

As well there were any number of print media interviews and TV appearances.

The Upward Spiral

Japan’s lecture circuit is cumulative.

The more you talk the more you become known; the more you become known the more you talk.

Eventually one’s name and profile begin to appear in the lists of speakers held by the various agents seeking commissions by introducing lecturers (the inviter, not the invitee, pays the commission).

The spiral is never-ending.

…

It can also spill abroad.

In those ‘Japan As Number One’* days, the outside world was keen to know more about Japan

That involved several trips to Hongkong and Singapore, which I enjoyed.

The Overseas Chinese had an intelligent interest in knowing more about the nation that had done so much harm to their country in the past, which had then been attacked and occupied by the US, and which was clearly prospering regardless.

A lecture tour of Southeast Asia organised by the Japan Foundation back in the days when it saw me as a ‘good gaijin’ was interesting enough too, mainly because it confirmed the weakness of the Japanese presence in that area.

That was followed by an all-nation tour of the US organised by the Japan-American Society. That taught me much about the US – both its attractive vitality and its ignorance of the outside world.

I even managed to get back to Australia once, care of Quadrant’s Robert Manne

2. Organising a Lecture

A unique aspect of the Japanese lecture circuit is the extraordinary effort put into preparation.

I used to compare it with the situation in Australia where, if you are invited to give a lecture, the inviting organisation feels it is doing you a favour in the first place. It expects you to organise your travel, and then pays you a pittance.

Not so in Japan. When a Japanese organisation decides to invite you to give a lecture, and you accept, you automatically become a Very Important Person.

You have done them the high honour by accepting to give a lecture.

(That is true at least for the time the lecture commitment exists.

(There is rarely much follow-up, apart from occasional requests to check the verbatim record some like to use for publication.)

…

First move is for them to send people – a seeming delegation sometimes – to your office for an uchiawase – a discussion of the details of your planned lecture and the logistic arrangements.

Even if the lecture is to be at the other end of Japan, sometimes they will send people all the way to Tokyo just for that uchiawase.

Only one of them will do the talking. The others will just sit there taking careful notes.

Often I try to suggest that we could decide all this over the phone, ideally with my secretary.

But no. They have to have that face-to-face meeting with the sensei before they can feel assured that everything will happen correctly.

Being reassured is very important for these people.

But for me it means that my schedule commitment is doubled – one for the lecture and the other for the uchiawase.

…

After the uchiawase come the phone calls to your office seeking confirmation of all those details, more materials, more reassurances, CVs, photos, resumes.

A brochure or flyer may then be prepared giving details of the speech you have promised to give. That too may be sent to you for clearance.

First class tickets to the town, village or city where the lecture is to be held are provided. Sometimes they will even send someone to Tokyo again, to make sure you catch that train or plane on time.

…

Eventually you arrive at the scene of the great event.

You will of course be met at the airport or train station by a luxury car and some attentive staff whose job it is to make sure to get into the car safely, and get to the lecture site safely.

Sometimes they will set your planned arrival time several hours in advance so everyone can be reassured that you will not be late.

There you will be met by some more senior but equally attentive staff. They will take you to a waiting room especially hired for your comfort. Somehow you have to fill in the several hours in advance arrival they have so carefully prepared.

As you sip green tea and make mild conversation, the top dignitaries involved with the occasion will file in politely to meet you. Cards will be exchanged.

After more green tea and conversation, a large flowery symbol of status, with your name attached, will be pinned on your lapel.

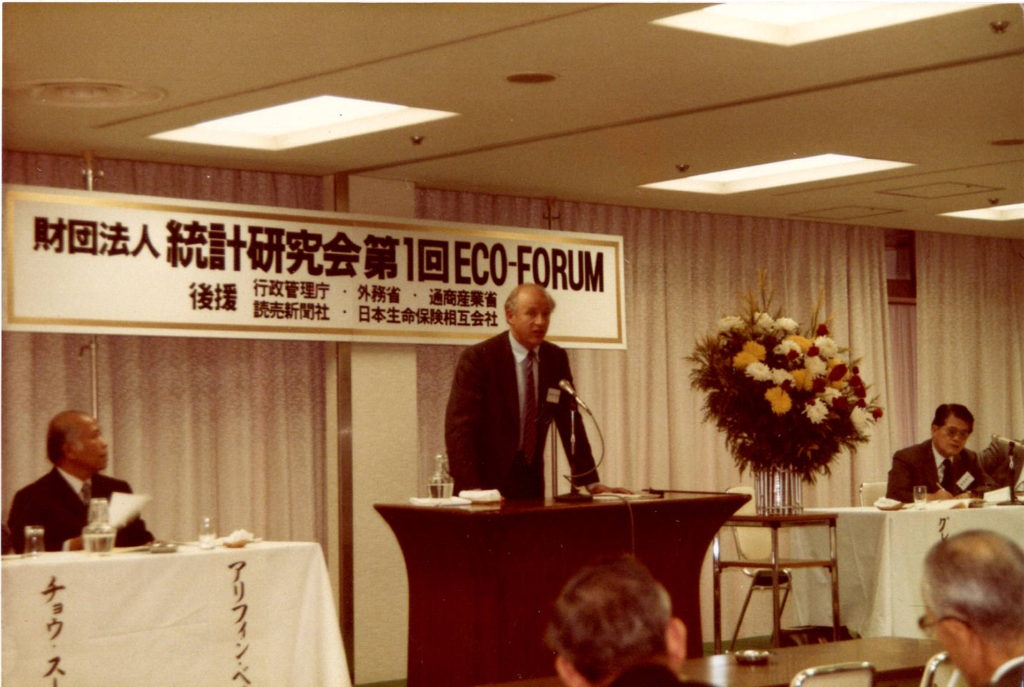

You are ushered to the podium. There you will be introduced in flowery language matching that lapel, by an attractive lady MC especially hired for the occasion. She will call for applause.

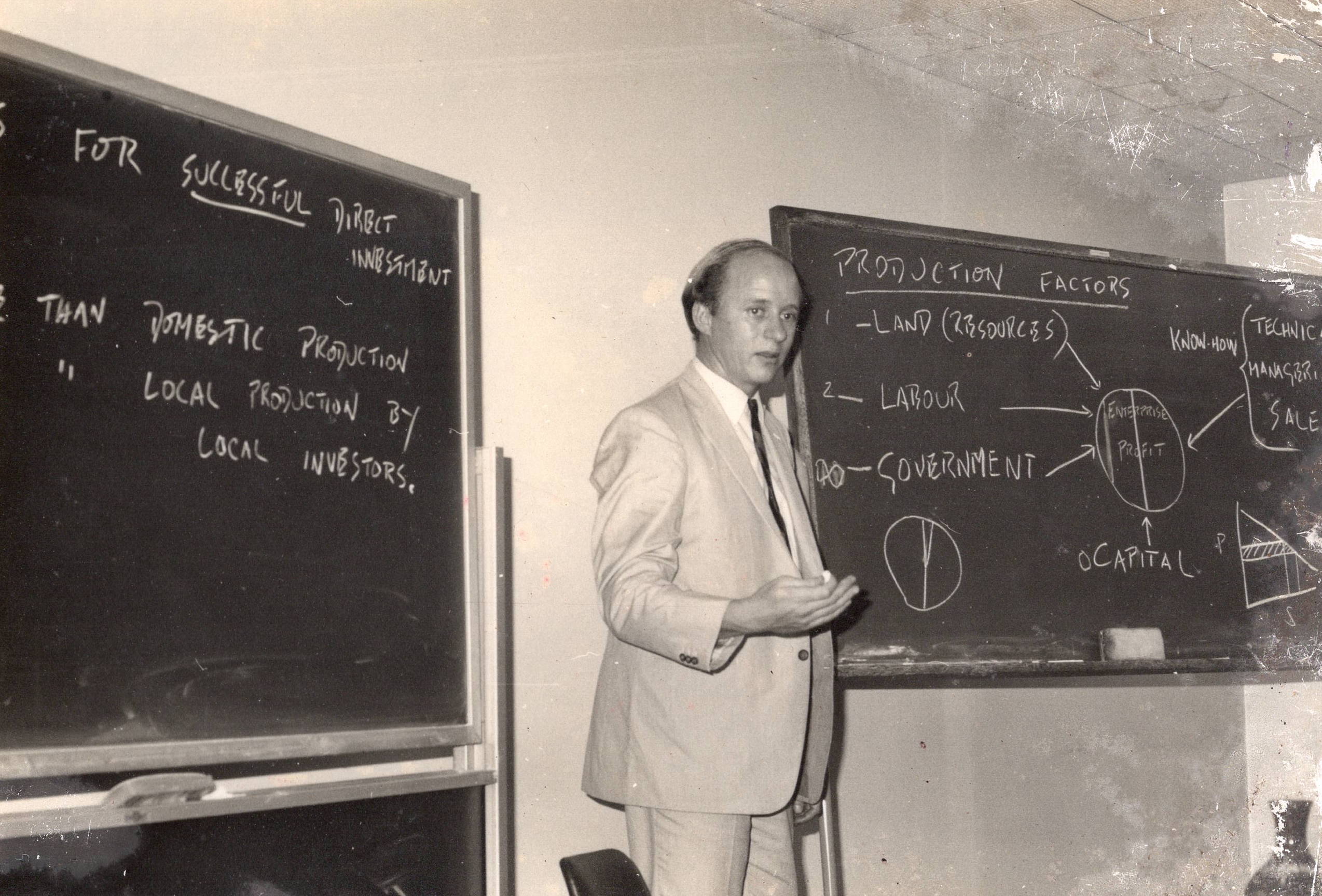

You talk for 60, sometimes 90, minutes. I often ask for a blackboard to help break up the routine.

Then in addition to more applause, you will receive a bouquet of flowers and a little speech of appreciation from one of the organisers.

Usually there are no questions; they are seen as too much of an imposition on the esteemed lecturer who presumably is in a hurry to move on to other important engagements.

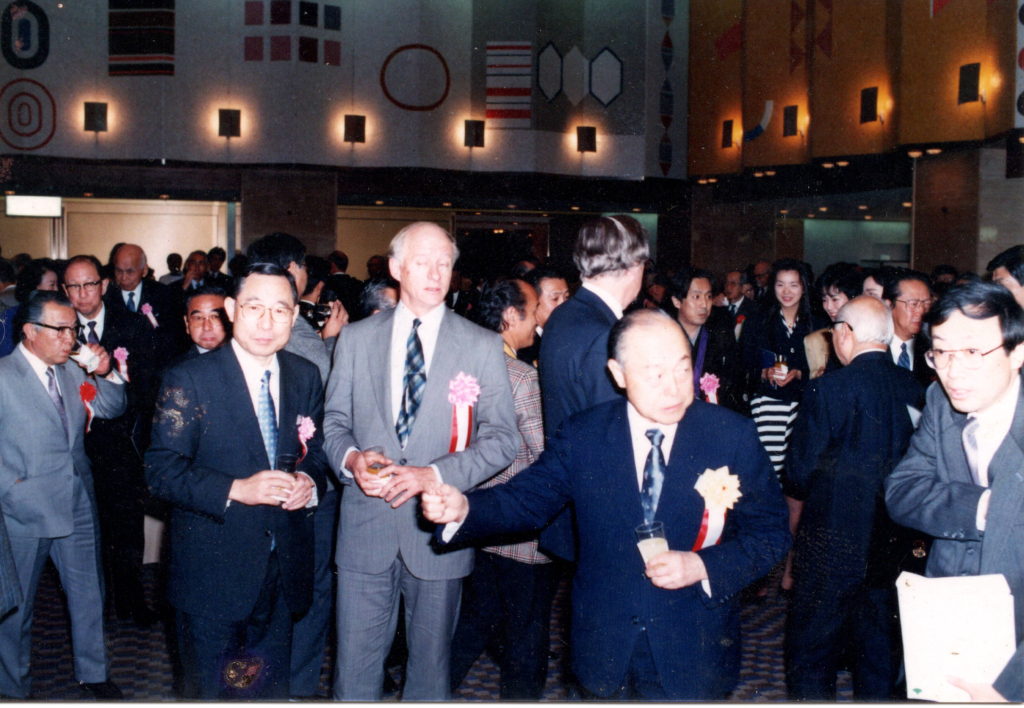

Or else they will say people can ask you questions directly at the expensive reception that usually follows these talkfests, and which you are free to attend if you want.

If you do attend you become the guest of honour, plied with food and drinks by charming hostesses

Then as you leave, the dignitaries line up to thank you once again.

You may receive a nice souvenir (often a quite expensive piece of local art) plus two presents — one to take back to your secretary with whom the organisers have now become firm telephone friends, and the other to take back to your family.

Meanwhile the attentive staff are still hovering around, determined to get you to your train or plane on time.

Usually they arrange it so you arrive at the station or airport around thirty minutes too early, just so they and you can be reassured that you will not miss that plane or train.

The thirty minutes is spent in more desultory conversation.

…

The time and personnel devoted to preparing for your lecture is staggering.

It is typical Japanese perfectionism. Nothing can be allowed to disturb the perfect timing of events.

It may be seen as something of an imposition at the time. But when it is all over you will be rewarded by an immediate entry to your bank account (never in 25 years have I been disappointed).

Sometimes you will be rewarded in cash handed over directly in envelopes.

3. Financial and Other Rewards

The financial reward in those Bubble days was staggering.

Even the total royalties from a well-written book could easily come to less than the reward for simply standing on a podium for an hour or so and enjoying the attention of a large audience.

But for me it was not just the money.

I was being paid to discover the nation which I liked and in which I had a deep interest.

I was being paid to get to places around Japan I would never normally get to, to meet people I would never normally get to meet, for opportunities to improve my Japanese, and to refine my original ‘Japan is a tribe’ theory.

No longer was I dependent on the goodwill of others for employment. I was now free to organise my life, just as I wanted.

Provided I got to those lecture appointments on time!