Chapter 46 – Back in Japan; The Book Published

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS and BETWEEN FOUR LANGUAGES

1. House Hunting

2. Finishing the Book

3. Publishing the Book

4. Launching the Book

5. A Newsweek Connection

6. Book Reaction

7. God Professor

It was, they said, the wettest and coldest spring on record.

Looking out over the drenched blossoms facing Tokyo’s Kokusai Bunka Kaikan (International House) guesthouse where I had rented a room for the family, I had to agree.

But the weather that early April of 1976 was not my only problem.

1. House Hunting

After a week or so at the guesthouse we had to move.

For a while we shuttled between some small apartments in the Harajuku area loaned by former journalist friends, dragging my family behind me.

It was not the grandest way to begin a new Tokyo career.

Worse, I had dislocated my shoulder lunging to grab a tree for balance while climbing the crumbling volcanic slope of Adatera-dake in Fukushima, with young Dan strapped to my back. That meant I could only type with one hand.

I was to do myself even more damage as a result.

‘In Fear of China,’ Again

With the Vietnam War over and China in the spot-light, Lansdowne Press wanted to reissue my In Fear of China book.

With one arm in a sling, I was trying to type up a revised introduction.

There was a lot I wanted to write about.

In particular, I wanted to flesh out my original thesis that the Cultural Revolution was no more than a ugly power struggle, with the Maoist faction using artificial ideological differences to humiliate and destroy all opposition – that it was not some irrevocable return to the mad, fearsome identity that China was always supposed to have possessed.

Events had proved me right – China was soon to show its ability to do a lot of sensible, moderate things.

But foolishly I decided to abandon the rewrite project.

Lansdowne asked me to put up the money needed to cover reissue costs. It was only 5,000 dollars.

But for me at the time, lacking both a typing hand and a proper job, it all seemed too much.

In retrospect, I should have been happy to pay far more to get the book republished.

That book was, and remains, one of more sensible things I have done in my life.

…

But at the time I thought I had more important things to worry about.

I was living on savings. We had to get young Dan into a kindergarten so that Yasuko and I could be free in the daytimes.

We had to find somewhere to live when the short-term rentals ran out…

…

But in retrospect they were also happy days.

They had a certain purity – our little group of three trying to survive in the ocean of Japanese society.

When you are down and out, even small triumphs have a clarity, joy and meaning they would not have otherwise.

The Yotsuya Pad

Eventually we decided to end our nomadic existence by pooling my remaining savings with Yasuko to buy a small apartment (‘mansion’ in Japanese) in Suga-machi – a rather run-down, lower middle-class area in the still unfashionable Yotsuya area.

By small I mean really small – one living/ kitchen room, plus two small six tatami mat bedrooms.

But it was also close to Sophia University, where I was already giving some lectures. It was also close to central Tokyo.

In the meantime I would try to make some money through bank translation work and editing a dialogue between Toynbee and Ikeda, the Sokka Gakkai chief.

I also had an unlikely JETRO job – judging films commissioned by JETRO to explain Japan to foreigners.

2. Finishing the BOOK

MM had been patient during the many delays in handing over the promised manuscript.

Eventually, almost a year later, I was able to give him something, and to begin thinking about a title for it.

I was in luck.

Japan ‘Unique’ ?

Simul’s book section was headed by one Tamura Katsuo – a mercurial man who had little patience with others, and the bad habit of abusing his staff.

But he also had publishing talents.

He listened briefly to what I had to say about the planned book’s contents (he rarely wasted time reading manuscripts, especially when they were in English).

I had suggested a title along the lines of Japan being different from the rest of the world (to match the title of the very successful The Japanese and the Jews book mentioned earlier).

Tamura interrupted to say that what I was really writing about was the ‘uniqueness’ of the Japanese people.

That, he said grandly, would be the title: Nihonjin: Yuunikusa no Gensen. “The Japanese: Origins of Uniqueness.”

I flinched. A title like that would fly straight in the face of the anti-Nihonjinron scholars.

‘Uniqueness’ was at the top of their list of taboo Japan words.

…

But Tamura had a point. If I was indeed saying that the Japanese were different from everyone else, then I was saying Japan was unique.

Even so, I was reluctant to use a word like ‘unique’ with its implications of racism and academic charlatanism. Apart from anything else, nowhere in the manuscript did the word ‘unique’ appear.

The title also sounded far too audacious, with me claiming, after all of five years experience, to be the final authority on the state of the Japanese nation.

(As it turned out, the first part of the title, Nihonjin, was to preempt the Japanese title of a book on Japan by the far more eminent Japan scholar, Edwin Reischauer, and also called “The Japanese.”

(His publisher ended up having to use a katakana title – Za Japanezu )

But publishers are supposed to know what makes books sell. And Simul was doing me the favour of publishing my already over-delayed and over-detailed book.

So I went along with what Tamura wanted.

And in so doing the book was to succeed in ways that even Tamura could not have imagined.

3. Publishing the BOOK

Simul had wanted to put the book out in Japanese first, with the original English to follow later.

They found me an excellent translator– Asano Atsushi, who went on to head the Japanese version of Newsweek and who died prematurely from what many saw as conscientious overwork.

The quality of his translation meant that the manuscript read better in Japanese than it did in the original English.

Which was just as well, because the English version was never to appear.

Following publication of the Japanese version, I suffered a problem common to many writers – putting the manuscript away for a while and seeing all its faults on rereading.

Writer’s tristesse, is what some call it.

I needed time for a major rewrite.

As well there was a rather bruising argument with MM over royalties for the English edition, with him insisting on the Japanese approach of a fixed percentage regardless of volume of sales.

But we needed never to have argued: To this day the book, although written in English, exists only in Japanese, with an English-language summary in simple English published almost ten years later, by Kinseido, and entitled ‘Understanding the Japanese’.

A ‘Tribal’ Interlude

In the process of getting the book prepared for publication I had an experience that ironically helped prove the topic of my book.

As author I had had to check the translation for mistakes (inevitably there are some, even with the best translation).

But various delays meant I had only 24 hours to check the final version before it went to the printer.

I had no choice but to stay in the Simul office all night going through the galley proofs.

Around eight AM the next day the hard-working and much-abused staff began to arrive (many of them would have been working late night to satisfy the vile-tempered Tamura).

As they saw me hunched over the table with a pile of galleys I could feel their attitudes change.

Till then I had been an outsider, someone to be treated with respect but not much more.

Overnight I had become an insider. I had sacrificed a night’s sleep so that they could get my book out in time.

I had become an honorary member of their tight little work group.

…

Years later they would talk of their surprise and joy at seeing me that morning, bent over a desk and still wearing yesterday’s clothes, labouring to help meet the deadline.

If I had needed further proof of Japan’s strong group ethic I had found it there, and right on the eve of publication.

Publishing Hopes

I was not unused to the excitement of seeing one’s book finally in print. “In Fear of China” had given me my first taste.

But there was something different about this book.

I was still trying desperately to make it in Japan. And all I could rely on was this little parcel of 307 pages with its audacious title.

But it said things I very much wanted to say.

It also allowed me to explain some things I did not like about our Western societies- in particular the propensity to foreign policy excess that had made my life so difficult in the past.

This in turn gave me what I saw as a path-breaking theory to explain how societies developed.

All I had to do was wait for the book reviews and maybe the world would begin to beat a path to my door.

And to some extent that is what happened.

But not quite in the way I imagined it would happen.

4. Launching the BOOK

Books need publicity. My ‘tribe’ book was no exception.

At the time I had to assume that my entire career in Japan would depend on its success. I had no other career alternatives in front of me.

Simul had done the best they could. They had run some prominent newspaper ads.

But Japanese newspapers are cluttered with ads for books, most forgotten in a few weeks.

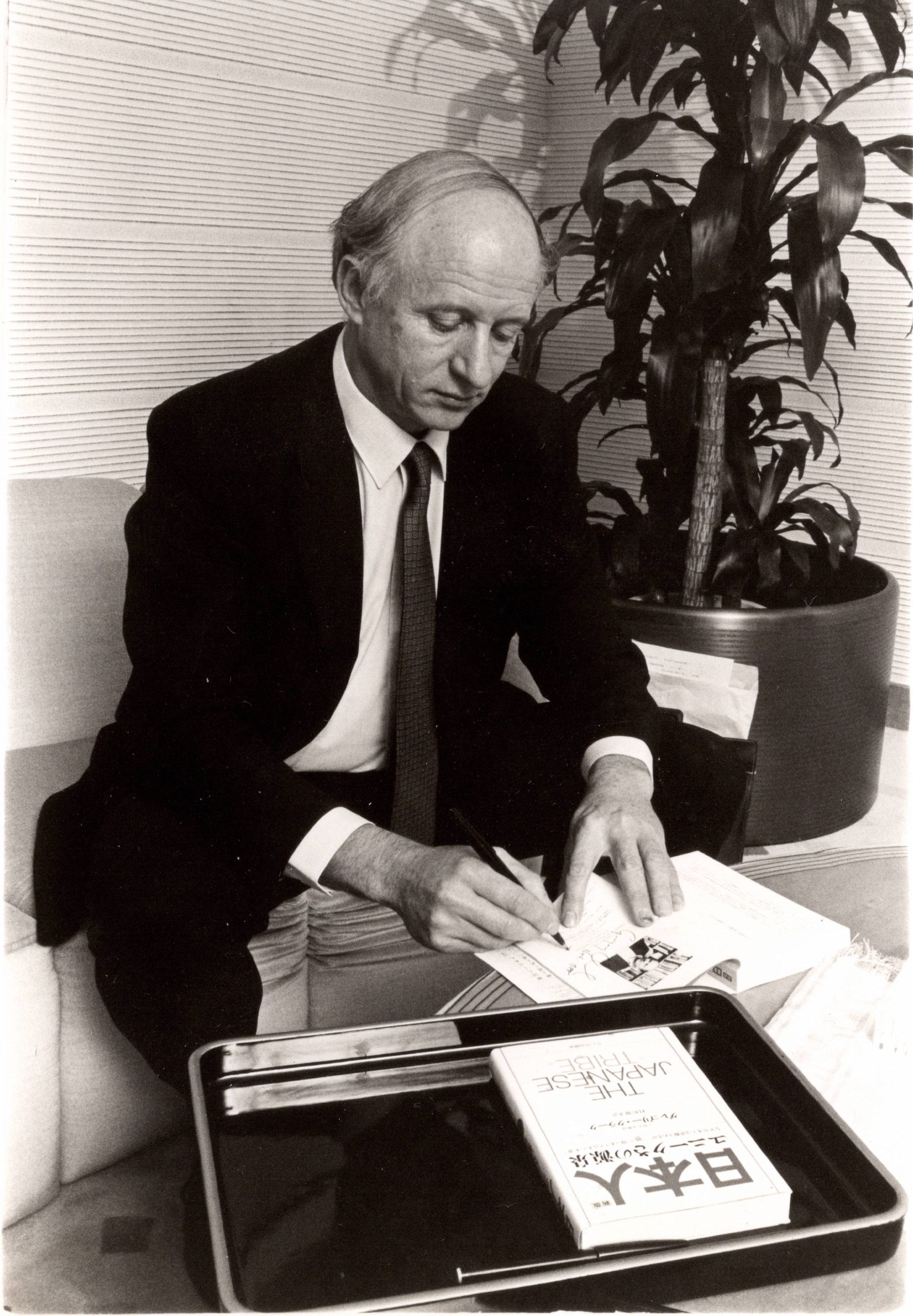

They had given me that sexy title for the Japanese-language edition (though at the back of the book I had been careful to insert a provisional English language title ‘The Japanese Tribe: Origins of a Nation’s Uniqueness’).

But even that would not be enough to guarantee publicity.

I had to come up with something different, and I thought I knew how to get it.

…

Buried deep in the book, somewhere around page 158, was a half-page mention of how Australian spies (the DSD operation in Melbourne to be precise) had been regularly intercepting and decoding Japanese diplomatic and business messages.

The story had been broken in 1975 by Brian Toohey, one of Australia’s best investigative journalists.

Splashed over the front page of the usually conservative Australian Financial Review, the scoop had sent spasms down Canberra’s collective spines.

A D-notice forbidding the Review or anyone else from following up on the story confirmed in effect that the original story was true.

…

I was in Canberra at the time and had waited for the shock waves to arrive from Japan.

They never came. The response from Japan was zero.

To me this was incredible. US success in decoding Japanese diplomatic and military messages had been the main reason why Japan had lost the war in the Pacific.

Unless Japanese memories were even shorter than I thought, there was no way they would want to ignore a story of this size and credibility.

Besides, Japan was supposed to be hyper-sensitive to anything we foreigners do that impinges on its reputation. If a reputable US or UK newspaper dares to use the word ‘Jap’ in a headline for space-saving reasons, for example, Tokyo lodges formal complaints.

Here was something far more damaging to Japanese pride, not to mention security, than the word ‘Jap’. And it was splashed all over the front page of an Australian newspaper.

But all we got from Japan was deep silence.

(I discovered much later that the story had in fact been picked up by Japanese journalists stationed in Sydney; they could hardly have not noticed it.)

(Collectively they had gone to Canberra to get the story confirmed by their Embassy there.

(The Embassy had insisted that the story was false – that there was no way the Australians could break Japanese diplomatic codes.

(The journalists had accepted this, and decided collectively not to report it. )

…

In my book I had retailed this lack of reaction from Japan to the Toohey article as yet another example of Japan’s ‘tribal’ attitudes.

But at the back of my mind was also the thought that if the story could be regurgitated closer to home, in Japan itself, it might create a few publicity waves.

When you are in the book-writing business, you need every wave you can get.

5. A Newsweek Connection

I had good contacts with the then Newsweek Tokyo correspondent, Bernie Krisher.

I told him how this important story about decoding Japanese diplomatic correspondence would be hidden away on page 158 or thereabouts of my book just about to be published, and that I was giving him an exclusive preview.

Bernie rose to the bait. The result was a whole page in Newsweek devoted to my regurgitation of the Toohey decoding story, just as the book hit the bookstores.

The top half of his article carried a seemingly larger than life photo of me shaking hands with the former Japanese Prime Minister, Sato Eisaku.

(It had been taken four years earlier during an interview with Sato at his Nagata-cho residence in advance of his planned visit to Australia. )

The bottom half gave the decoding story, written up as if it had just emerged from the mouth of the former ‘senior Australian government official’ shaking hands with that former prime minister in the photo above.

6. Reaction to the BOOK

Within 24 hours of Newsweek hitting the Tokyo streets, almost all the main media outlets in Japan, and quite a few abroad, were trying to contact me for confirmation and more details.

Many wanted interviews. Some wanted TV appearances.

And thanks to the Newsweek story, all wanted to assume that it was I, not Toohey, who had broken the decoding story – a misapprehension I tried hard to disabuse.

(As mentioned earlier, during my 1975 stay in Canberra I had not been cleared for receiving top secret decoded or other materials. I had, after all, opposed the Vietnam War.)

(However, I had been cleared many years earlier when working as a young Foreign Affairs official.)

(I saw then the fruits of the decoding operations. For me Toohey had simply confirmed the bugging continued.)

So even though I had stumbled across hints that a decoding operation was underway while in Canberra in 1975, I could also say in all honesty that I was simply retailing the Toohey story and writing about the surprising lack of reaction to it in Japan.

In short, I was not revealing state secrets.

But I was also less than unhappy to see Canberra put on the spot.

It was claiming a special relationship with Japan while actively cooperating with the Echelon operation against Japan. It was typical of the diplomatic duplicity I had sacrificed career to oppose.

Out of obscurity

Thanks to the Newsweek article, I went almost overnight from complete obscurity to full limelight exposure.

Fortunately a few also began to read the book.

Originally I had feared there might be some reaction from nationalists and others over my having described Japan as ‘tribal.’ There was none. (’Tribal’ does not have the same overtones as it has in English.)

All the main newspapers and quite a few others ran favourable reviews. Asahi gave me a large, front-page interview article.

Most picked up my emphasis on such obvious things as Japan’s groupism and emotionality, as though I had made some amazing revelation.

However one or two progressives — Kato Shuichi for example – seemed not to like my idea that a long history of isolation was the cause. They preferred to see the machinations of Japan’s establishment as responsible.

(Many foreigners also found it hard to accept the central thesis of the book – that the attitudes they see in Japan as quirkish could in fact be quite natural, even if exaggerated, aspects of the human psyche; that it is the quirks of us foreigners which need to be explained.)

All this attention soon led to regular appearances on NTV’s (Channel 4) morning program, Seso Kodan (popular discussions) hosted by well-known commentator, Takemura Kenichi.

Less known then was the caster – the demure, and later Defense Minister in the Japanese government and then governor of Tokyo, Koike Yuriko.

(I got to know her quite well. She seemed reasonably smart.

(But the idea that she should emerge almost thirty years later as a top LDP hawk handling national security matters and then as Tokyo governor seemed very remote.)

The icing on the cake, so to speak, was being asked to join popular writer, Fukada Yusuke, in hosting a regular bimonthly NHK 30 minute program, Shin Nihon Jijo, where the pair of us interviewed in depth Japanese-speaking foreigners doing interesting things in Japan.

Japan was just starting to move into its kokusai-ka (internationalisation) phase. It was keen to know what we foreigners were up to, and how we saw Japan.

Soon this totally unknown foreigner (myself) was being established firmly, if somewhat bewilderingly, on Japan’s media map.

7. God Professor

The good news did not stop there.

Because of the book I was soon to end up as a brand-new, fully-tenured professor (kyoju) at a prestige university.

It is a title and a status that opens many doors in Japan.

This is how I think it happened.

…

Whenever I went on TV I had myself identified as ‘visiting professor’ (kyakuin kyoju) at Sophia University.

By Japanese standards this was not incorrect, since technically I was still ‘visiting’ Japan on a short-term visa from my former academic slot at the ANU.

But the people in charge of Sophia administration were puzzled. Few had even known about my existence.

Who was this foreigner claiming Sophia credentials and appearing so regularly on TV?

Father Joseph Pittau, the intelligent European Jesuit who had skilfully used Japan’s internationalisation boom to drag his once humdrum university to the reputation it enjoys today, was the Sophia University president at the time.

(He later became a top official at The Vatican.)

It seems it was he who decided that since Clark was giving the university such good TV publicity, then maybe they should drop the ‘visiting’ in his title and make him a full professor.

Be that as it may, a few months after book publication I got a hint that I could apply for a professorship.

Soon after I had a sudden request to present my publications (of which there were quite a few). Some weeks later I was a full professor.

And since my formal academic background was in economics, I was given a dual professorship – one in the Economics Department (with which I had had no previous contact), and the other in the International Department where I was already lecturing.

…

I took me some time to digest the changes.

Normally, academic promotion, both in Japan and Australia, means decades clawing one’s way up a slippery academic ladder. Even then, the top positions are far from guaranteed.

In my case it had all happened in a matter of weeks.

True, I think I had the academic credentials to accept such an offer.

I had already published in Japanese and English the results of my research into Japanese direct investment abroad.

My ‘In Fear of China’ book had been translated into Japanese, and some Japanese scholars of repute (Nakajima Mineo for one) had realized the originality and significance of my research into the origins of the Sino-Soviet dispute.

Finally, there was my Japanese Tribe book which, for all its amateur sociology, did at least try to explain Japan.

But I was in no mood to query how and why this good fortune had descended on me. I just accepted it as it came.

Overnight my future in Japan had been assured, if I wanted to stay there.

And soon another even larger and equally unforeseen fortune would descend on me – the Japanese lecture circuit.