Chapter 71 – AIU. More Attempts at Education Reform

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS and FOUR LANGUAGES

1. A Book on Education Reform

2. Akita International University

3. Trying to Improve English Language Teaching

4. Teaching Current Affairs

5. Japanese for Foreign Students

6. Trying Improve Business Japanese Reading Ability

7. One Small Satisfaction

When I finished at Tama I felt I had to publish something about Japan’s education system.

Here I would be relying directly on my own experiences, plus those of my sons.

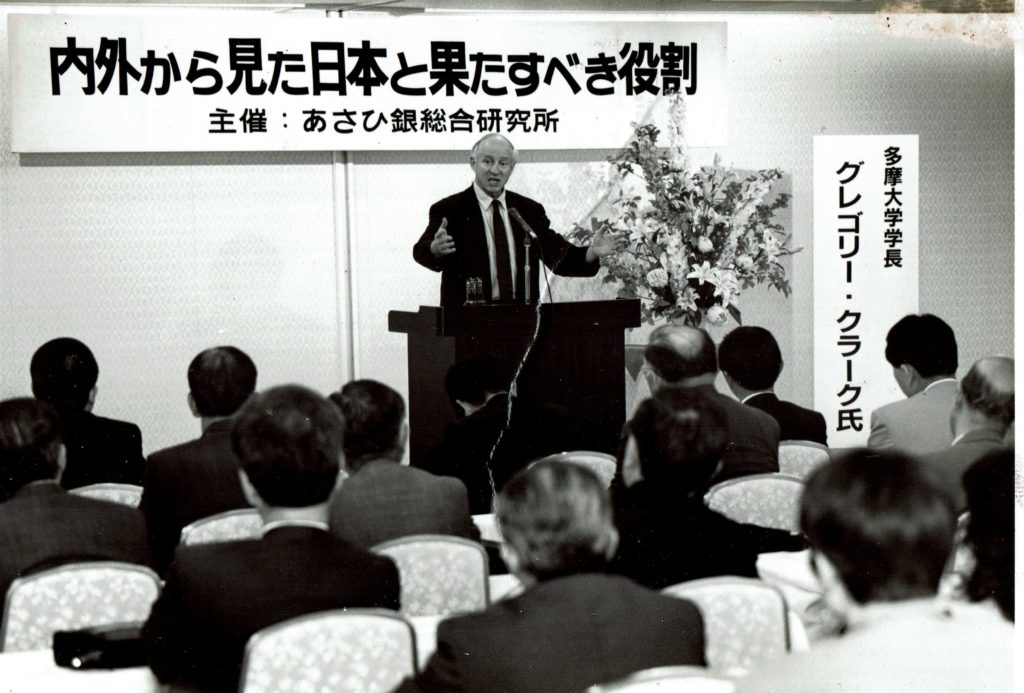

Few foreigners could claim to have spent the best part of thirty years in the system, not to mention any number of official committees on education reform.

If I could not do anything about Japan’s messed up economy then maybe I could do something in the education area.

Or so I thought.

1. A Book on Education Reform

My key theme would be the need to bring motivation to the classroom, and the ways this could be one.

I had seen the energy Japanese students could show when motivated -when doing what they wanted to do – organising school festivals, clubs, scientific experiments, interesting research projects.

How could this energy be channeled into everyday classroom education? And how could the teaching of English be reformed?

Over the years I had refined my ideas. Now was the time to produce a book.

Choosing a Publisher

But foolishly I relied on a personal connection to link up with Toyo Keizai as publisher. (I knew they were more involved with economic and business issues, but they did have a progressive reputation and had been good to me in the past).

Yasuko, as ever, did her uncomplaining best to put the text into good, readable Japanese.

But Toyo Keizai were simply looking for a short, sharp quick-seller.

They wanted, they said, something the average salaryman could skim through without too much effort.

When they said a cartoon was needed to introduce each chapter I realised we were in trouble.

They did little in the way of publicity or courting book reviews.

It ended up as an over-sized 320 page tome, cartoons included, entitled Naze Nihon no Kyoiku kawaranai no deska? (Why Japan’s Education does not change?).

It was typical Japanese publishing opportunism – rely on the name of the author to sell enough to cover costs, with a small profit and a minimum of expense.

A lot of effort, and ideas, went into that book for little result, which was a pity since those who did get to read the book were positive about the ideas.

But I was writing at a time when Japan was already moving away from wanting to hear what the foreigners had to say, particularly if they were critical.

And maybe by this time I should have realised there is a limit to the time Japan retains interest in new stars and fads. But I did owe an apology to Yasuko.

2. Akita International University

One hope, I thought, would be my involvement with the new university in Akita (Kokusai Kyoyo Daigaku) I mentioned earlier.

It promised a new approach to education. Through its obligatory one year study abroad system it would be developing a strong network of foreign relationships.

In particular I had hoped to get involved with its language teaching efforts.

Maybe that would be an area where I really could do something useful, since we were attracting good students, many keen to master languages, and not just English.

A book I had published in Japan many years earlier on the processes and techniques for language acquisition had had a good reception.

Here would be a chance to test out some of those techniques, and maybe get enough material for another book, or so I thought.

3. Trying to Improve English Language Teaching

But once again there was frustration.

The PhDs in linguistics we employed to teach English, partly at Education Ministry insistence (PhDs seemed to be requirements even for the PE teachers), were determined to do things their own academic way.

Some seemed unable even to learn to speak Japanese properly. Yet they claimed to be the experts in teaching people how to learn to speak English!

Teachers of languages other than English also had their textbook hangups.

Yet the need for proper teaching, especially to improve listening ability, should have been obvious: Apart from anything else the students had to try to listen and understand all the English language lectures they would be required to attend.

…

I tried to introduce the code decyphering (ango kaidoku hoho) technique I had written about in that earlier book.

In other words, first choose some material the understanding of which is important for your studies, hobbies, current events etc.

Tell yourself that the text has obstacles to understanding – secret codes that have to be deciphered. Create a challenge in your mind.

Listen repeatedly to the text to try to work out the pronunciation of those mystery words, and only then turn to dictionaries or available translations for the answer to the mystery.

Then try as quickly as possible to use the word in conversation.

And write it out also perhaps (writing is good for memory). It links the visual image (the writing) to the hearing image you have just acquired,

…

For materials to use, a good start for the AIU students would be the recordings of their curriculum lecturers.

Most teachers spoke too quickly, with few concessions to students’ comprehension problems.

Students tended to end up relying on the set books or text handouts after class, just to find out what the teacher was talking about.

Discussion or questions were impossible.

The only problem, amazingly, was that some teachers objected to their lessons being recorded. And they called themselves professors!

…

As a result of my hectoring AIU did offer to create something a bit similar.

They called it focussed listening, but the classes were not run along the lines I would have preferred.

4. Current Affairs

I had also hoped that for students who planned to enter the real world later, whether in Japan or elsewhere, there would be more emphasis on economics and current affairs.

Japanese universities, including our own at Akita, were graduating students who did not even know the meaning of 9/11.

(All students are notorious for lacking knowledge of the world around them. But Japanese, with their steady diet of comics, anime etc., are probably worse)

My idea of the ideal current affairs course was simply to require students to read the main English language newspapers every day for a year, and then discuss them in class with the teacher – in English

At term end they would be examined on whether they remembered the topics discussed during the term.

No boring lectures would be needed.

But that idea also got turned down.

5. Japanese for Foreign Students

As AIU began to get a reputation abroad as almost the only university in Japan with most teaching in English our numbers of exchange students rapidly increased.

These were students staying only for a year or two, usually in exchange for their universities accepting our students for the obligatory one year abroad.

It was an ideal situation for us, especially since we could usually have them sharing boarding rooms with our Japanese students.

Most of them, naturally enough, wanted to learn or improve their Japanese. But they would also have to help their boarding companion with his or her English.

…

I would dearly have liked to revive the kind of course I mentioned earlier and that had worked so well for my Sophia students for the teaching of Japanese.

But teaching of Japanese was a no-no area dominated by some elderly Japanese ladies steeped in tradition. They were not going to listen to the ideas of some foreigner.

If I could do little to influence the teaching of English at AIU there was even less I could do to influence the teaching of Japanese.

The most I could do was to claim some of the credit for having helped the university to get set up and running.

7. One Small Satisfaction

But as other universities began to imitate our model -all classes in English, an imitation inevitable in Japan’s copy-cat society – maybe collectively we could all claim some credit for improving education in Japan.

Some even copied word for word the names of our classes.

At last count AIU quality was rated number 14 of all the universities in Japan – well ahead of some of the more famous.

That provided some small satisfaction for all our efforts…though the sight of a classroom with students able and willing to debate issues with teachers would have provided much more.