Chapter 63 – Seeking Education Reform – Failures and Successes’

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS AND FOUR LANGUAGES.

Seeking Education Reform

1. The Committees

2. The Education Ministry

3. The National Peoples Commission of Education Reform

4. The University Education Sub-Committee.

5. The High-school English Language Committee

6. Reform Impossible. A Book

Education ‘reform’ was another problem needing attention.

It was a topic I welcomed greatly. But it involved committees, which I disliked greatly.

1. More Committees

In the late nineties reform of the education system suddenly emerged as a popular national issue.

Global comparisons showed standards were slipping. Firms were unhappy with the quality of new entrants.

Not just the Education Ministry but the entire business world seemed anxious to claim education reform as their own area of special interest.

And as a foreigner working in a Japanese university I had come to be seen as an expert on the topic.

At one stage or another I was to find myself involved with all three committees set up by the business community – Keidanren, Doyukai and Nikkeiren (Keidanren was by far the most serious).

The Education Ministry had me on several of its reform committees, including one Shingikai (a formal ‘government policy recommendation’ committee).

Even MITI, determined to be part of the action, set up a committee with me as the titular chairman.

But I never discovered what was the MITI connection with education.

And none of them could come up with anything useful

Keidanren had the bright idea of asking companies to let employees go home early at least once or twice a week so fathers could have dinner with their children.

(Lack of parental communication with children was seen as a serious cause of weakness in the education system.)

Doyukai and Nikkeiren simply offered the usual panaceas.

Few seemed to realise the key issue – the need to provide clear study motives and challenges for students, university students especially.

I had always been impressed by the zeal young educated Japanese could show when facing a challenge – organising annual school festivals in particular.

Months in advance they would begin setting up committees and sub-committees, each charged with organising particular events — one for food, another for music, or for greeting visitors as they arrived.

Students had the energy. All they needed was a motive – a clear challenge for them to conquer.

But in the classroom there was little motive or challenge. Japan’s group ethic worked in reverse.

Those who tried to excel were seen as swots and found themselves pushed outside the egalitarian group.

The aim for most – for the male students mainly (female students were more individualistic) – was to stay a member of the anti-swot group and do the minimum needed to graduate.

They felt proud of that – proud enough even to boast for years later about how they had graduated without opening a textbook.

And many of the teachers were willing to cooperate with this fraud.

The alternative – to fail the entire group of student slackers – was impossible.

It was against the rules. The university reputation would suffer.

Besides, to fail one’s students that was to deny one’s own validity as a teacher.

So giving passing grades to that bunch of slackers was proof of one validity as a teacher?

…

In communist societies it was joked that the workers pretended to work. And the system pretended to pay them.

In Japan it was different: The students pretended to study. And the teachers pretended to teach them.

…

But it was not until I got onto the Education Ministry committees that I realised fully the difficulty of serious reform – though eventually, alone or together with some others, I was to see some reforms implemented.

2. The Education Ministry

Even more than other ministries, the Education Ministry liked to pretend to rely on the ‘experts’ – a motley collection of academics (myself included) with the occasional businessman or commentator inserted.

In fact the Ministry had little interest in what we had to say. At meetings its bureaucrats would sit at the far end of the discussion tables, bored and half asleep, knowing that they had already prepared a final report reflecting the ministry’s views, not ours.

A favourite theme of our committees was urging stricter regular testing of students as the solution to all problems.

But given the lack of rewards for good study (employers were only interested in seeing what university you graduated from, not the quality of your degree) and the virtual impossibility of dismissing bad students, what, I often asked, could the universities possibly do with those who were happy simply to do the minimum needed to graduate?

Here the only answers I could get were silence, or garbled remarks about relying on the good conscience of students and teachers.

I was witness to a curious Japanese phenomenon – the belief that if you set out beautifully-worded idealistic goals, that was enough to realise those goals.

3. The National Peoples Commission on Education Reform

Eventually I was to get the chance to be involved in one genuine attempt to realise a few reform goals

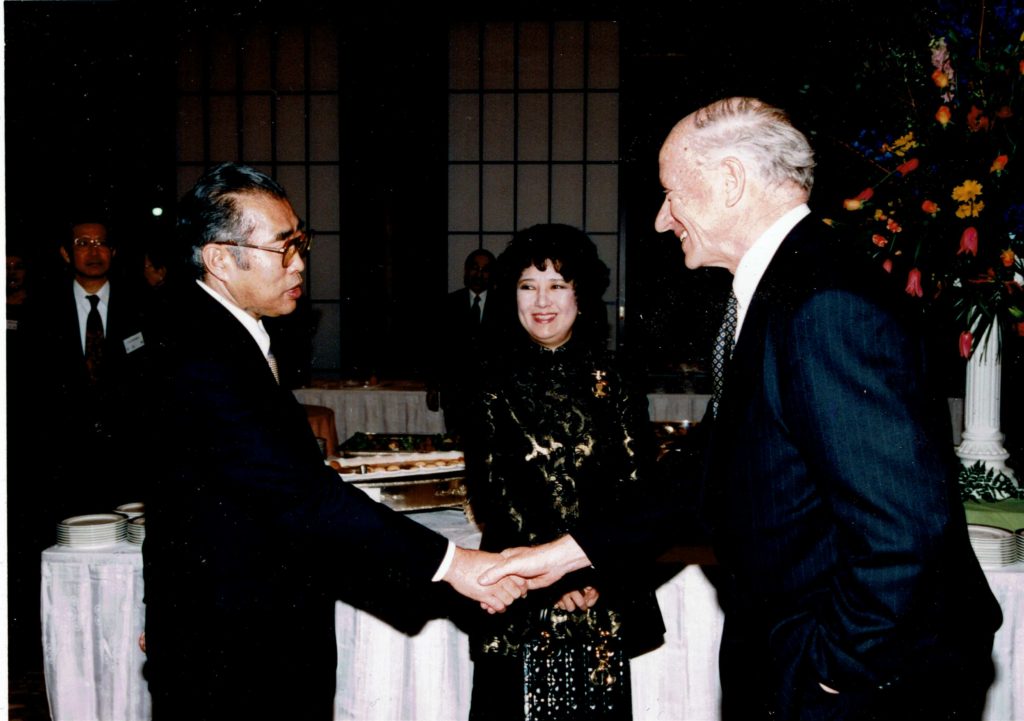

I had met Prime Minister Obuchi Keizo once or twice before, and liked him.

He seemed to remember me, and when he set up his 1999 ‘National Peoples Commission on Education Reform’ I was made one of the 26 members (even though I was clearly not one of the ‘national people’).

(But the fact that by then I had become president of a small Tokyo university, Tama, may have helped.)

We would usually meet in the prime minister’s residence – me driving up in my battered Boso vehicle while the others arrived in expensive hire-cars or company vehicles.

Plenary discussions were fairly platitudinous. And distracting too – 26 people facing the prime minister and looking out into beautifully manicured residence gardens.

With each member determined simply to put forward his or her own ideas about how to reform things, constructive discussion was even more difficult..

…

I had my day in court with the story of how my son had spent two years at a top high-school studying chemistry without being allowed even once to use the school science laboratory.

(They were told they could learn everything needed for top university entrance exams by memorising the textbooks.)

But few other than the sensitive and intelligent Obuchi seemed to take in what I had to say.

The others were too full of their own ideas and complaints.

…

There were many agitated calls for more volunteer and outdoor activities by students. But few practical suggestions.

My own recommendation – much greater support for Japan’s weak Boy Scout movement – had few listeners (though it did result in my being made a director of the Boy Scout national organisation, where I found it was being choked by old-men bureaucracy – the fate of many similar youth and sports groups in Japan).

4.The University Education Sub-Committee

Fortunately I was also able to join the smaller and more compact university education sub-committee, with the bright, up-and-coming Machimura Nobutaka as our political minder.

There, discussions were much more serious and to the point.

I could put forward several ideas for university education reform I had long felt were important.

These included opening up the admissions system with a category called ‘provisional entry’ (zantei nyugaku – probably my one and only contribution to the Japanese language incidentally).

This would allow provisional entry for students near passmark in Japan’s notorious entrance exams.

They would be given another chance to show entrance suitability – a challenge to which I was sure they would respond — with another exam to folllow.

(Years later at Akita International University I was able to try out the idea.)

(Often the provisionals would end up doing better that the regulars. Why? Because the challenge was clear and concise.)

…

Another proposal was to allow September entry, in addition to the traditional entry in April. That would make it easier for many foreign students to enrol.

(Since others were making the same proposal it was widely adopted.)

As well I argued there should be encouragement for gap years and volunteer activity, and ‘double major’ systems to allow for intensive language study, either as a major or a minor.

(Gap year is now widely accepted.)

…

A special joy was the fact that since we were a Cabinet committee we were superior to the bureaucrats.

They had to sit clustered together at the end of the room, listening to what we had to say, in terror that we would want to do something to upset their bureaucratic equanimity or control.

I pushed hard for a relaxation of the extraordinary rule preventing any student, no matter how brilliant in say math or science, from entering university before age18.

I pointed to the recent news that a girl aged 12 had managed to enter Oxford for mathematics.

But the bureaucrats were upset by the confusion 18-year old entry might cause in the school convoy system where everyone moved up together in strict age cohorts.

One of them even piped up to say that age 18 entry was dictated by law.

For one glorious moment Machimura leaned across the table, looking down on them with contempt.

‘Well, change the law,’ he barked.

And that in fact was done. A year later a law was passed allowing university entry at age 17.

That, and all my other recommendations, got into the final report – an amazing contrast with the fate of ideas I had put forward formerly in Education Ministry committees.

The idea of September university entry was eventually to become popular nation-wide, making it easier for international exchanges and for students to go out and get some adult experience between school leaving in March and university entry.

And one or two universities were to try out my provisional entry idea (zantei nyugaku) to loosen up entry exam rigidity.

But most of our ideas were to be emasculated by the bureaucrats, or ignored by the universities.

The law allowing entry at age 17 was filled with obscure, hard-to-meet conditions.

No one, as far as I know, has followed up on it.

(I should add that a few years earlier the president of Chiba University had put me on a committee handling his demand that bright math or science students be allowed entry at age 17.

(The bureaucrats had reluctantly approved the demand, but only as a short-term experiment, with strict conditions calling for close screening and special ‘emotional care’ for those allegedly immature 17 year olds thrown into competition with 18 year olds.

(Dozens of us worked almost a year on various Chiba university entry committees to manage the change. But we could get only 11 applicants nation-wide, of which only three were selected.

(A year later the university dropped the experiment.

(But five years later I was to come across a Nikkei article about a 23 year old genius taking a MIT doctorate course in physics.

(I remembered his name. He was one of the three we had selected!

(He said that but for the early age 17 entry it was likely he would have ended up as a Tokyo University graduate aiming for a bureaucratic career.)

5. The High-school English Language Committee

Soon after I was to be put on another Education Ministry committee, this time to consider high-school teaching of English.

Previously English had only been a middle school subject.

I and some others argued that given the bad teaching to be expected in the high schools, forcing all students to undergo three years of compulsory high school study would do more harm than good.

I argued that the three years of basic study in middle schools – age 12-15 – was sufficient for most.

Only those who wanted could continue to study English at high school, in special separate classes and with qualified teachers.

(I knew from my own experience the motivation was even more important in language learning than with other subjects. People cannot not be forced to learn languages.)

Students who did not want to do English at high school would be able to spend more time studying math and science, areas where Japan was admittedly getting weaker.

And to help reform of high school English, universities should cooperate by making English an elective, not compulsory, in their entrance exams….

I went out of my way to say I was not arguing that study of English was unimportant.

On the contrary. But learning English and other languages should be concentrated at the universities, I said, using the double major or major-minor system that worked so well at US and Australian universities.

There, students would have the valuable incentive of knowing the language they were studying could possibly help their future careers.

Three-four years of concentrated university study of a language of choice, beginning age18, with good teachers and equipment could provide students something close to workable use of the language, if not fluency.

Under a double major, or major-minor, system university students choosing business and Japanese, or Chinese and law, for example, could easily end up with excellent careers.

But requiring universities to make English an elective subject for university entrance was crucial to this reform.

If language was a compulsory subject most would end up reluctantly receiving three years of generally bad high school teaching of English, which does more harm than good. They would also be reluctant to continue study at university.

Even more than with other subjects motivation is crucial for language learning. (My own experience of learning Chinese did not begin till age 22 but that worked out fine since I knew it was crucial for my career.

(The idea that only small children can learn languages properly is exaggerated.)

But none of this wisdom made it into the final report. Indeed, the final report said we all agreed that language study at high school should be compulsory (previously it had nominally been elective).

When I challenged the ministry officials in charge, they admitted that since the final report had been prepared in advance it could not be changed to reflect mine or any other contrary opinions.

So why had we been asked to waste a year of committee attendances? No reply.

6. Reform Impossible? A Book

Finally I began to realise the impossibility of serious educational reform in Japan. The bureaucrats had already made up their minds.

Language study was an area where I had some experience, but my views counted for nothing. And this was an area where Japan was seriously lagging, losing out internationally as a result and badly needing some fresh ideas. ….

In frustration I was eventually to write a 300 page book about my various education reform ideas and experiences – Naze Nihon no Kyoiku Kawarani no desuka? – Why does Japan’s Education Fail to Change?

But personal relations led me to choose a bad publisher – Toyo Keizai.

They made little effort to publicise the book. I would be surprised if it had much impact.

Meanwhile, trouble was developing on my home front, Sophia University. The time spent on those committees was not helping much.