Chapter 50 – A New Life In Japan (1978 – early 1980’s)

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA;

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS AND FOUR LANGUAGES

Like a Jolt from a Rocket Launcher

1. Finding a House

2. Finding an Office

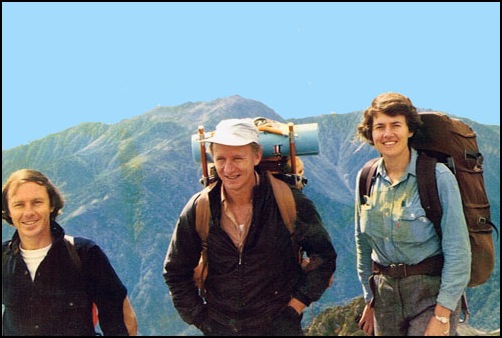

3. Mountain Climbing (photo)

4. Involved in Boso

5. More Book Creation

6. The Japanese Government Committee

7. Committee Games

8. The Role of the Foreigner

9. Inside the Committees

10. My One Contribution to Japan? The Tokyo Symbol Mark

11. The Lecture Circuit (continued)

12. Japanese Jokes

13. ‘Heartful’ Talking

14. Back to the Japanese University

In just one year my life had changed dramatically.

Early 1978, I am 42years of age and I am still a refugee from Canberra’s confused politics and Australia’s futile academism.

The best I can do is become a part-time lecturer at Tokyo’s Sophia University, eking out extra income from translations and odd jobs and with no visible future other than the manuscript of a book in my desk drawer.

Early 1979, the book has been published. As a result I am a full professor at Sophia University and a regular face on Japanese national television, quoted heavily in the print media, and launched firmly on Japan’s endless lecture circuit.

The sudden jump from total obscurity to all-Japan notoriety was rather like the jolt from a rocket launcher.

You can suffer some gravity problems as a result.

1. Finding a House

First priority was to improve living conditions for self and family.

With another child on the way -Ron- the need was growing.

I do not crave luxury living, but the extraordinary income coming in from the lecture circuit also meant there could be some lifestyle changes.

First move was to get out of our tiny Sugamachi apartment and find ourselves a piece of land with a house on it, which we did, in the Akebono-bashi district, also fairly close to central Tokyo.

The house was very old and the sellers had planned to pull it down before sale. But it had an old-world traditional feel about it.

When we discovered it would cost them three million yen to demolish the house we told them to leave it on the site and reduce the price of the land by three million, which they did.

So we ended up living in a house with a negative value of 3 million yen.

But the land was not cheap (around one million yen a tsubo, or 10,000 USD per 3.3 square meters). The land boom was reaching its peak. And much work was needed to make the old house liveable.

Second Child, Ron, Arrives

We had never established a family plan: too many other things to organise first.

But in the euphoria of getting the Tribe book finished, Yasuko found herself pregnant again.

Fortunately, Ajiken Ken gave generous time off to have a child, so chaos was minimal.

The only problem was choosing a name.

I was anticipating a girl and had a dozen or more good candidate names lined up (girl’s names that go well in both English and Japanese are numerous – my choice was Erika).

But it was a boy – sleek and elegant, but still a boy.

Ron was one of the few bilingual names available – not knowing young Ron would turn into a champion marathon runner and that the name of Ron Clarke (a future world champion) carried a resonance he could share.

But if we were to stick to the bilingual plan we to find a suitable Japanese character for Ron. There are not many.

Fortunately, Yasuko’s father was a backroom classical scholar. He had the good idea of using the character Ron (meaning virtue) in the first half of the Japanese word for London (Rondon).

…

Family expanding, a few years later we were to build another and more conventional house in the small garden alongside the old house, and move there.

The old house was rented out to various foreigners, including the US academic and Japanologist, Carol Gluck.

She had firm ideas about house decoration. To my initial unhappiness she threw out all the remaining traditional junk in the house – old wooden shutters, ancient tatami etc – and replaced it with chic shoji and a sunken kotatsu.

Later I had to admit she was right, though we disagreed a lot about Japan and its history.

I think she saw me as one of those distasteful Nihonjin-ron people

2. Finding an Office

Next move was to get out of my cell in Sophia and set up a proper office in the well-located Kojimachi area near the Nagata-cho Diet complex and close to Sophia.

(The tiny rooms allocated to professors at Japanese universities could not even provide space for interviews, let alone a secretary.)

(Most academics on the lecture/TV guru circuit also have to seek offices outside, which does little to endear them to their colleagues remaining in the cells.)

The Kojimachi office occupied the basement in the house of a retired banker, Kazuro Sonoda.

Brought up in Germany during the war years, fluent in German as a result, and with certain aristocratic pretensions (his five story house was on some formerly palace-owned land next to the Akasaka Prince hotel), he made sure I knew my place in the basement.

I had also hired a part-time assistant — a Sophia student who was supposed to be studying law but seemed to know little more than the details of the Japanese Constitution.

She was a typical product of Japan’s irresponsible, and in those days still leftist, university education system.

3. Mountain Climbing

Meanwhile I was still absorbed by my second occupation – the attempt to climb all the higher mountains around Tokyo. A photo of me during that period shows someone happily liberated from the troubles and frustrations 2-3,000 meters below.

But by a series of accidents I also got myself involved in land development. It kept me fit and taught me a lot about flowers, trees and bulldozers. But it was very time and attention consuming.

Gregory Clark with friends in Japan’s Southern Alps – 1978

Whether or not in the process I did serious damage to a promising career as academic, writer and commentator depends a lot on whether I could have had such a career in the first place.

4. Involved in Boso

It began with my chance discovery of the vast Boso Peninsula to the south of Tokyo, which I described in the previous chapter.

It ended up with me trying to manage a community housed in 30-40 houses and bungalows scattered over hills and valleys on the east side of the peninsula.

In between I also tried to hold down several university jobs, continue to give lectures across the nation and to put out about dozen more books.

Of the books by far the most successful was the one that gave me the least trouble – a slim paperback which took all of two days to prepare.

5. More book creation

Kodansha, a leading publisher, had asked me to do a follow-up to my Japanese Tribe book.

But this time it would be in taidan (dialogue) form, with me discussing my ideas about Japan with an up-and-coming rightwing Japanese celebrity, Takemura Kenichi.

I would not have to write anything myself, they said. I would just talk.

Takemura’s favourite message to his devoted audiences was to say that what was commonsense (joshiki) in Japan was non-commonsense (hi-joshiki) in the outside world.

My ‘tribe’ theory about Japanese values being in many ways the reverse of our non-Japanese values slotted in to this neatly, even if our politics differed greatly.

Kodansha hired a room for us in a luxury hotel. For two days we were fed, wined and listened to while we talked into a tape-recorder.

A first-rate Kodansha editor, Suzuki Satoru, then pulled our ramblings into a neat little 190 page paperback in the Gendai Shinsho series.

Titled Yuniiku no Nihonjin — Unique Japanese – the book was to go through 18 printings and sell something like 160,000 copies, far more than the original Japanese Tribe book from Simul (though Simul, like most Japanese publishers, never gave me full sales figures).

And to think that it had only taken me two days to produce!

The Kodansha book gave an added fillip to my lecture circuit.

And soon the requests to join Japanese policy making and advisory committees also began to flow in.

That too was to be a highly educational, if fairly time-consuming, affair.

6. The Japanese Government Committee

The first invitation had been to a committee set up by then Prime Minister, Ohira Masayoshi (1978-80).

I had had contacts earlier with him as a journalist, and respected him as one of the more intelligent and liberal-minded LDP politicians.

(As foreign minister, he had been crucial to Japan’s opening of relations with China back in 1972.)

As mentioned earlier the committee was set up to discuss Ohira’s favourite concept of garden-town development (denen toshi kaihatsu).

The Ohira invitation was to be followed by many more. Eventually there would be requests from almost every Ministry or agency of policy-making importance in Japan.

At last count there were 43 of them (the full list can be seen in the Biography/CV on this website). Only the Foreign Ministry avoided me, for reasons that later will become obvious.

And it goes without saying that I was not invited to anything in the Defense Agency (through one of their think-tanks once did invite me to give a speech about the former Soviet Union).

Many of the committees were mere front operations aimed to give some kind of respectability to devious bureaucratic operations. But some occasionally provided a good look into the workings of Japan Inc.

So I persevered.

7. Committee Games

The proliferation of committees is one of Japan’s stranger phenomena.

It owes much to Japan’s much-mentioned consensus ethic – to the way bureaucrats and politicians like to appear to have appealed to and considered public opinion before they hand down new policies.

And to some extent, in the postwar years at least, when I first arrived and Japan was a much humbler and poorer society, this search for consensus was fairly genuine.

There was a real effort to promote the national interest and to have Japan regain its position in the world.

Opinion polls were frequent. When the public turned critical, the bureaucrats listened.

Today much of this has changed. Zoku* (‘tribe’)-minded bureaucrats and politicians specializing in specific and narrow areas of national policy are in control.

For example, we have the doro (road) zoku of politicians and others with a vested interest in building roads. And so on.

Preserving the territory and interests of the area covered by one’s zoku or ministry is the main aim. The national interest is often secondary, or even irrelevant.

(Many in the West may have been misled by Chalmers Johnson book ‘MITI and Japan’s Economic Miracle’ written in the wake of this earlier, humbler period.

(It did much to create the image of dedicated Japanese bureaucrats devoted to the national interest and whose strong control from the top was the key to Japan’s successful economic growth.

(Today, some have come to realise that bureaucratic and political tribalism and lack of strong control from the top is a major factor hindering Japan’s successful progress.)

But this territorial narrowing, if anything, made the bureaucrats and politicians feel even more the need to create policy-advising committees, to prove they were still in touch with the national consensus.

…

The committee-making routine was well established.

First you find a collection of so-called yuuishiki-keikensha – ‘knowledgeable and experienced people’ – to serve as ‘experts’ on the committee. These ‘experts’ are people who, with one or two exceptions, can be expected to agree generally with what you want to have approved.

Then you call them together for a much-publicized opening meeting covered heavily by the media.

As the faces of the ‘experts’ flash across the nation’s TV screens that evening, the public is encouraged to believe that the bureaucrats and politicians really are trying to come up with policies that are best for Japan.

Then comes a succession of two-hour meetings (this time largely ignored by the media) where detailed briefing materials are supplied and read out at length.

By the time the reading out is finished there is usually little time for more than a few desultory remarks among the members, followed by some discussion about the date for the next meeting.

A few months later the committee will then meet to approve a final report, prepared by bureaucrats and allegedly taking into account committee views.

But for the most part it is recommending the policies that the bureaucrats wanted from the beginning.

Often those final reports are prepared in draft even before the committees get underway.

*(zoku is usually translated in the media as ‘tribe,’ though it can also be translated as gang, as in boso-zoku –- hot-rod motorbike gangs.)

8. The Role of the Foreigner

How does a foreigner like myself come to get involved in all these committees, some of which, in theory at least, were supposed to discuss questions of national policy?

I too still wonder. But there is what I call the ‘lubra’ theory.

When the officials set up their committees they like to recruit a few other than the regular panel of ‘experts’ they use, to show they really have tapped into a broad cross-section of the society.

Often some notable from the sporting or artistic world will be included.

I once sat through ten committee sessions on some trade issue with a sumo wrestler who did little more than grunt.

Then when the female emancipation movement of the seventies got underway, the demand was for at least one female on any committee.

I once spent the best part of a year on a MITI committee to discuss global economic policies, and which included a rather attractive haiku lady who did little more than look demure for the entire time we were in session.

Then, with the onset of the ‘internationalisation’ (kokusaika) boom of the eighties, there was also the demand for a foreigner or two to be appointed to committees.

It reminded me of Canberra in the Whitlam years when the political correctness said the voices of the infirm, the female, the aborigines and the non-heterosexuals should all be heard in the corridors of power.

The ideal candidate for a Whitlam committee was said, rather cruelly, to be a one-legged lesbian lubra.

(Note: a lubra is a female aborigine person.)

I lacked several lubra qualifications. But as a Japanese-speaking foreigner attached to the well-known Sophia university, and, more importantly, sometimes free during day time hours, I was an obvious choice at the time.

The few foreigner women with similar qualifications were even more in demand.

9. Inside the Committees

Many of the committees I joined turned out to be fairly meaningless. But some gave a good inside view of the bureaucratic and political process in action.

They also told me a lot about the personalities of the ‘experts’ being appointed to the committees.

Since some of those alleged experts were quite influential in moulding Japanese opinion, it was good to see them close up in action.

Needless to say, most were highly conservative. Discussions were usually rambling and fairly meaningless.

But the materials prepared for these committees were often useful for my own research.

Some were even marked secret. Amazingly, the Japanese organisers seemed not to worry about a foreigner reading their secrets.

One reason could be that until time of writing at least, Japan had none of the secrecy mania that infects Western societies.

Another reason could be more cultural.

As a member of the committee I was automatically an insider to the group. The fact that I was also a foreigner was secondary.

As such I was just as entitled to the information being given to the rest of the committee, even classified information, and denied to the world outside.

But insider or not, only rarely could this humble foreigner exert any real influence.

10. My One Contribution to Japan? The Tokyo Symbol Mark

Indeed, the one concrete policy shift I can claim credit for in those early years was on a committee set up to chose a new symbol mark for Tokyo.

Votes of the other 12 members were evenly split, so I had he casting vote.

As a result Tokyo today has the simple, clean, green leaf symbol used on all official documents and buildings, rather than the complicated mess that six members had preferred.

Other Contributions

In short, the many hours spent sitting around those long, cloth-covered committee tables were not entirely wasted.

Years later, on an immigration policy reform committee I was able to help ease Japan’s draconian policies to illegal migrants.

Instead of being thrown into jail, deported and told essentially never to come back, they were allowed to leave legally if they declared themselves and return after one year.

(I was also able to discover the genuine concern that even educated Japanese had that relaxed immigration policies threatened social cohesion.)

11. The Lecture Circuit (continued)

From my earlier description (chapter 22) the reader should already have some idea of Japan’s extraordinary lecture circuit.

There was the sheer volume – an average of around two-three lectures a week to audiences of every type and size all around Japan.

And there was the variety of audiences – businessmen, nurses, teachers, bureaucrats, average citizens, even farmers sometimes.

When one is giving much the same lecture, day after day, month after month, even an initially poor speaker such as myself begins to learn something about public speaking, and about Japanese audiences.

How to Lecture

First lesson was that Japanese audiences are extremely sensitive, much more so than you might realize from their often deadpan expressions.

From the moment you walk onto the podium they are watching you closely.

You have to show full confidence; they can tell very quickly whether you are at ease with your subject.

You learn to talk slowly and carefully at the start, giving the impression that you have something important to say later (Hitler is said to have used the same technique).

You have to create rapport. And you have to maintain it for an hour and half – the normal time for lectures in Japan.

You are not allowed to flag, even for a moment; once the audience senses hesitation or doubt, they switch off. It is hard to recapture them.

But if you capture them well from the start and keep them captured they will listen, and well.

The attention is both intelligent and genuine; their reactions to strong points and jokes are good indicators.

Most try hard to avoid showing doubt or boredom towards the lecturer, unlike Western audiences which turn off or even turn hostile if they do not agree with the speaker.

If all goes well it is as if you have managed, single-handedly, standing on your isolated podium, to elevate an entire audience, sometimes several thousand people, and hold them there.

One begins to realise how dictators come to love to orate.

In my case I suspect the attraction was not so much the oratory, but the fact I was a foreigner trying to speak their language – the talking dog.

….

But there was also a genuine interest in what the foreigner was saying.

Often I was putting out ideas new to Japanese audiences. ‘‘Thank you for saying things that ‘hurt our ears’ (mimi ga itai)’’ was one common reaction.

Another was ‘you have made the scales (uroka, or fish scales) drop from our eyes.’

A further help was the fact that I seem to have mastered what I call ‘the Japanese joke.’

12. Japanese Jokes

In the West, jokes or humorous asides in speeches are expected, demanded even.

Not so in Japan.

Most Japanese speakers take themselves very seriously. Either they don’t know any jokes, or else they feel that delivering them detracts from their status as the esteemed sensei handing down wisdom to the masses.

Needless to say, as a stray foreigner wandering the country I lacked such pretensions. I was more than happy to use jokes, or humorous asides, if that helped keep the audience on-side.

Sponsors and audiences would then tell me how much they appreciated this, as if being humorous was a quality quite unexpected in a university professor.

Jokes would have to be simple, with little of the subtlety of Western jokes. Puns were popular. Irony was a no-no.

A favourite ‘Japanese joke’ was a true story about myself, new to Japan, trying to order food in a sushi bar and thinking that when they recommended okonomi sushi that would be the cheap dish.

I had misheard okonomi (specially selected sushi) for ekonomi – economical. Only when I got the bill did I realise my mistake.

I ended up with a few dozen of these ‘jokes.’ Scattered throughout the standard 90 minute speech, they worked well.

Another quality for which I was sometimes praised by sponsors, but of which I was hardly aware, was the ability to handle pauses (ma).

For some reason ma are important for Japanese listeners. They communicate something serious. he nature of which I am still not sure.

In any case, plenty of ma.

13. ‘Heartful’ Talking

Finally, and I guess this goes without saying, the easiest way to hold an audience, any audience, is to speak from the heart.

I could do that because I was genuinely interested in my subject — namely, the differences between the Japanese and us non-Japanese, and the reasons for those differences.

In effect I was being given a chance to talk directly to the subjects of my research, free of charge.

Normally a researcher has to pay good money for that opportunity.

Talking of heart, a popular lecturer around Japan at the time was Hayasaka Shigezo, former secretary to Tanaka Kakuei.

To show sincerity at key moments, Hayasaka would remove his shirt, jump up and down violently, and sweat profusely. The audiences loved it.

I could not compete with that. But before good audiences — school teachers were the best — it was not hard for me to get deeply involved in what I wanted to say.

Sometimes I could even draw tears – for example, and as proof of Japan’s closed nation mentality I would often talk about Japan’s conservative reluctance to allow organ transplants.

As a result numbers of Japanese children were going abroad for operations.This meant the Japanese child often had to be given priority, which meant that foreign children also waiting for the same transplant would suffer and possibly die through being excluded from the priority list.

Even so, we foreigners were still willing to give the Japanese child priority.

When the child returned cured, Japan’s media and public would erupt with delight. They seemed to show little interest in the fact that Japan’s obstinate refusal to allow the transplants at home would be causing problems for children abroad.

…

The lecture circuit had other benefits.

The pressure of standing on a podium and trying to communicate to a large audience forces one constantly to rethink, simplify and expand ideas.

Discussions and questions also helped, when they happened.

Thanks to all that I was able to refine my original ‘tribe’ theory of Japan into something much more sophisticated than the original, but also much easier to explain.

But while time-consuming and sometimes interesting, the committees, and the amazing lecture circuit, were always peripheral to what was what supposed to be my real job in Japan — teaching, and then managing, at a university.

14. Back to the Japanese University

In Japanese a dual faculty position is called a kentan.

At Sophia I had been given a kentan covering two areas— the Faculty of Economics, and the International Division (now known as the Faculty of Comparative Culture).

It meant two lecture schedules, two different faculty committees to attend, two different sets of academic intrigues to cope with, and two very different languages in which to operate.

Worse, I was being asked in the Economics Faculty to give lectures, in Japanese, to vast halls seating one hundred or so bored students taking basic economics courses.

I have a fairly good constitution. But sometimes just thinking about having to give one of those excruciating lectures used to make me sick in the stomach.

After about three years of this purgatory, I was suddenly told that the kentan had been terminated, that I should confine myself to the International Division position.

At the International Division life was much easier. Faction fights and boring faculty meetings could be ignored or bypassed.

Teaching was in English. The lecture burden was light, and could be concentrated into two days of the week, giving me more time and leeway for the still expanding committee and lecture circuits.

More in the next chapter …