Chapter 32 – Three Post-Pingpong Visits to China

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS and FOUR LANGUAGES

Trade Minister, Jim Cairns, May,1973;

Prime Minister, Gough Whitlam, November, 1973;

Deputy Prime Minister, Jim Cairns, October,1974.

With Whitlam elected as prime minister in November 1972, diplomatic relations with Beijing were quickly established.

In the space of little over a year I would end up making three more visits to China.

One was to cover the opening of the embassy there, which was combined with trade minister (and later deputy prime minister) Jim Cairns leading a group of top Australian businessmen on a trade mission to China in May, 1973.

The second was to cover Gough Whitlam’s historic visit to China as prime minister in November, 1973.

The last was to cover a trade exhibition opened in Beijing by Jim Cairns in October,1974.

The visits did little to teach me about Australia-China relations, which were still very limited in those days.

But they did teach me a lot about China, and about Australian politics.

I.The Cairns Trade Mission to China, May 1973

1. Cultural Revolution Factories

2. A Cambodian Connection

3. The Penn Nouth Photo

4. No Recognition of Sihanouk

5. Canberra Reprimands Cairns

6. Chinese Ingratitude

7. Cairns Personality

8. Australian Iron Ore to China?

With the Australian recognition of China in December, 1972, following the federal election victory of the ALP earlier that year, Jim Cairns, then Trade Minister, moved quickly to organise a trade mission to China.

The timing was clearly to take advantage of the excitement over the prospect of a new large market opening for Australian goods.

Cairns had with him the cream of the Australian business community. But the Chinese showed little excitement.

They gave little sign of realising Cairns’ political significance as head of Australia’s embattled leftwing in those days.

(Whitlam was still much more interested in keeping his credentials as a centrist, even as the disaster in Vietnam was unwinding).

(For the Chinese, the tiny pro-China ALP breakaway faction in Melbourne seemed to be the focus of their political attention.)

1. Cultural Revolution Factories

After Beijing we all set off on a Potemkin-like tour of China.

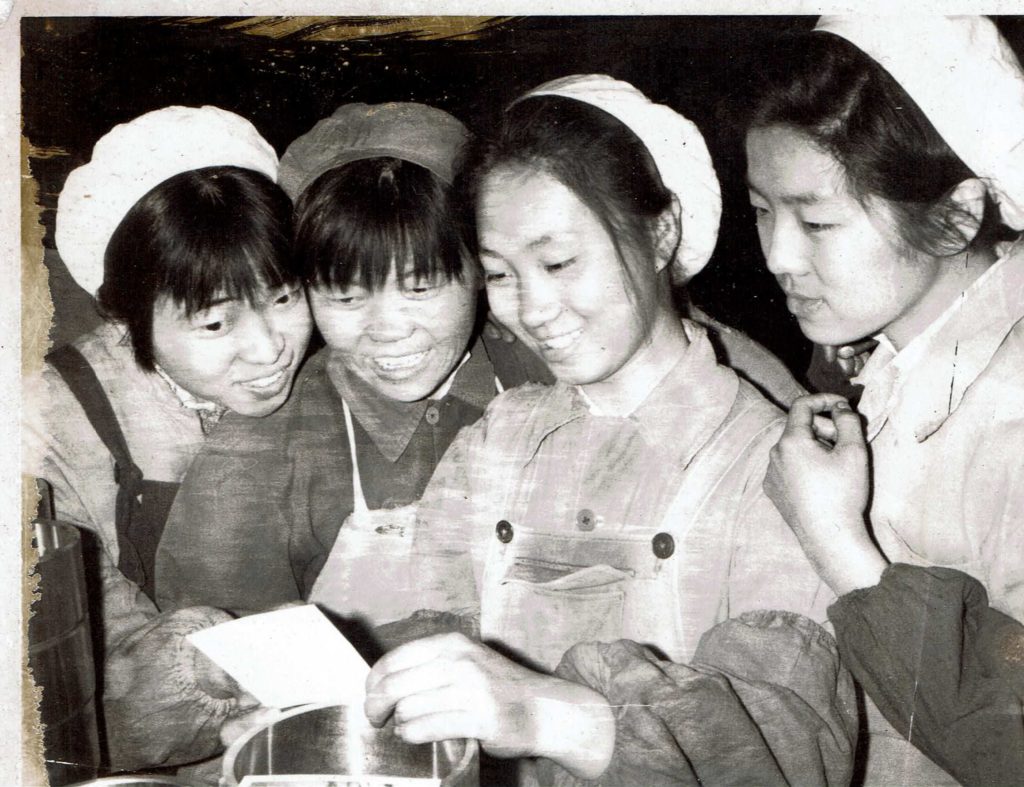

As we wandered round factory after factory it was obvious that the Chinese were far more interested in handing out Cultural Revolution slogans than in serious manufacture.

We visited a factory allegedly making transformers somewhere in the countryside outside Shanghai.

After we got into our cars for the trip back to town, I decided for toilet reasons to go back to the factory – something I could do fairly easily because my car was the last in that carefully-protocoled car queue.

A few minutes earlier the factory had been a scene of concentrated industry, with workers too busy even to glance at us foreign visitors as we wandered through.

Now, just a few minutes later, it was deserted. It had all been a purely show performance.

2. A Cambodian Connection

One useful result from the Cairns May 1973 visit was a move to open contact with the Cambodian government in exile.

On the 1971 ping-pong visit to Beijing I had got to see Sihanouk, then already in exile from his native Cambodia where the US had installed the puppet Lon Nol regime.

(Who today even remembers the names of people like Lon Nol, Nyguen Ky and a host of other military types the US had tried vainly to install as leaders in Indochina?)

(The US is unique in many ways. One is that it does not even bother to pretend to preserve the façade of its puppets when their CIA-installed regimes collapse.)

Sihanouk had invited me and some others to the very comfortable house the Chinese had given him. He had shown us a film of the then emerging Khmer Rouge guerrilla armies.

He was relying on them to overthrow Lon Nol and bring him (Sihanouk) back to power.

As I looked over faces of the young, dedicated, guerrillas – many female – lined up in the jungle I was reminded of the photos Burchett had shown me some years earlier in Moscow of the emerging Vietcong armies in the South Vietnam jungles.

For me the honesty and truth of a revolutionary army can be judged by the willingness of young people, women especially, to volunteer for it.

By that standard,e the Khmer Rouge, in their early stages at least, had to rank high.

(Later, I was to dread the murderous B 52 US carpet bombing raids these young people would have to suffer.

(Elsewhere I describe how I was to meet one of those uncaring murderous B 52 crew at Anderson Base in the Phillipines.

(‘Just pretty green fields’ was how he described his targets.)

3. The Penn Nouth Photo

During the 1973 Cairns visit I set out to renew my earlier Sihanouk contact.

I was able to arrange for Cairns to meet with Penn Nouth, prime minister in Sihanouk’s government in exile.

With my trusty Polaroid camera in hand I was also able to get a good photo of this historic meeting.

It went directly on to the front page of The Australian the next day.

(An irony of China in those days was that it was much easier to send photos abroad than text. The former could move uncensored.)

By my standards it was a good story, though my journalist colleagues were not so admiring.

They saw it as quite unfair, for example, my being able to use my earlier political contacts with Sihanouk and Cairns to get the Penn Nouth story.

I recalled the UPI photo manager who said he hired ‘photogs’ not on the basis of camera ability but by the political sense to get to find out how and when to point the camera in the right direction and at the right person.

My colleagues were experts in finding and sometimes beating up stories. They had equipment to match. But they were sometimes weak in realising political targets for photos.

…

My other problem was the virtual contempt they had for anyone of their group, myself included, who spoke any Chinese.

That too seemed unfair to them — that it was un-Australian to be out there yabbering away in a language no real Australian would ever want to learn or speak, and using it to gain advantage.

One sensed the contempt when they asked us to interpret for them. I was tempted to say we were not their servants,

4. No Recognition of Sihanouk

Opening contact with the Sihanouk regime should have been a top priority for any progressive regime in Australia anxious to see stability and democracy in Asia.

But Canberra was not impressed by this Cairns initiative for the meeting with Penn Nouth.

To its eternal discredit, the Whitlam government, with the rightwing Lance Barnard as deputy prime minister, was insisting that the US puppet, Lon Nol, was the sole legitimate ruler of Cambodia.

5. Canberra Reprimands Cairns

Unbelievably, Cairns received a formal reprimand for seeming to flout the government policy of not recognising any aspect of the Sihanouk regime.

(Earlier in Tokyo I had seen Barnard turn quite hostile when someone suggested that Australia’s support for the Lon Nol regime was misplaced.)

(How do the intelligence agencies and other uglies get at these rightwing ALP types, and why do they succumb so easily, and remain dumb for so long?

…

I also tried to arrange for Cairns to visit Sihanouk. That plan was killed by direct order from Canberra.

Ironically, Whitlam, on his November, 1973, visit to Beijing just six months later, was to gain media bouquets for going out of his way to call on Sihanouk.

The rivalry and jealousy between Whitlam and Cairns was to do a lot of damage to ALP foreign policy formation over the years.

6. Chinese Ingratitude

For the 1974 exhibition Cairns had persuaded many Australian firms to spend a lot of money to bring their goods to China for display.

With great difficulty he even brought a model airplane – the Australian-produced Nomad.

But the Chinese did little to help him.

They gave little sign of realising the political capital he had expended in organising the exhibition.

They not only purchased little. When the exhibition ended I discovered the Chinese were insisting the exhibitors had to take all their goods back to Australia.

Failing that, they had to hand over their exhibits to China for free or else pay good money for their disposal.

…

Needless to say, Cairns was not impressed when I wrote that story.

Later he was to make sure that I was not included in the press coverage for his next overseas trip (to Hanoi).

He chose a rightwing Singapore based reporter instead.

7. Cairns Personality

As I mentioned earlier, I had had dealings with Cairns back in the anti-Vietnam war

protest days in Australia. I had found him both very supportive at times and quite disinterested at others.

This time too he remained as complex as ever— a hard man to get to know properly.

He was determined to see China as the leader of some great liberating revolution in Asia.

Yet the shambles of the still lingering Cultural Revolution were visible on every side.

…

Our brand-new Beijing embassy was even less impressed by my reports, since it undercut badly their claims that Australia had a great trade future in China.

Which it was to have eventually, but not by selling Nomads.

As it turned out I was to discover the precursor of the great trade future myself —right in the middle of Beijing at that very moment.

8. Australian Iron Ore to China?

During the 1974 visit, walking the Beijing streets, I ran into an old contact from my Hamersely and CRA visiting days — Tom Barlow (who was later to head Hamersely).

He did not want to admit it, but he was in Beijing to arrange the first contract for export of Australian iron ore to China.

I had pestered him into giving me the name of the hotel he was staying at so I could arrange a follow-up talk (he had been trying to keep journalists at bay but I was relying on our past friendship).

But when I tried to contact him at that hotel I was told insistently – in Chinese – that there was no Barlow there.

I did not think Barlow would deliberately have given me the wrong hotel name. So I persisted.

It took me some time to realise that Barlow in Chinese means the eighth floor (baa low), and the hotel only had five floors!

I eventually linked up with Barlow though he did not want to talk much about his mission. But it was clear that something big was on the move.

In fact it was to become a story that would rescue the Australian economy.

They do not get much bigger than that.

2. The Whitlam November, 1973, visit.

1. The Anti-China Briefing

2. The Foreign Affairs Minister, Alan Renouf

3. The Unreliable Mr. Renouf

4. Deng Xiaoping and other Non-Scoops

5. The Mythical Mr Weidashping

6. Back to Australia, Temporarily

In November, 1973, Prime Minister Whitlam felt he should visit Beijing to mark the opening of an Australian Embassy in China. During the visit I was to see more of Canberra’s still lingering anti-China wisdom.

Eric Walsh was traveling ahead as PR for the mission.

1.The Anti-China Briefing

Eric showed me the confidential briefing for the visit which, unbelievably, was reciting the usual rightwing platitudes about Chinese aggressive intentions in Asia, as if there had been no change of government in Canberra.

(I was to discover much more of the same during my 1975 stay in Canberra, of which more later.)

That story, when published, caused me considerable unhappiness from the Whitlam camp, and the Australian embassy, which were trying to pretend that Australia was now a good friend of China.

Clearly the bureaucrats back in Canberra had their own ideas what Australian policy should be.

2. The Foreign Affairs Minister, Alan Renouf

Whitlam had brought with him his newly-appointed Foreign Affairs chief, Alan Renouf, another former anti-China official now trying hard to pretend to be progressive minded.

Renouf promised me all kinds welcome if I ever wanted to come back Canberra and into his Department.

‘Greg, we need people like you.’

Two years later when I did get back to Canberra, he went out of his way to make sure that I never even got near his Department

3. The Unreliable Mr.Renouf

Renouf was a devious personality.

His previous posting had been Washington, where he had played a key role in making sure Canberra got militarily involved in Vietnam.

But the moment Whitlam was elected he began a not very subtle campaign to persuade the ALP that he was a progressive and a longtime admirer of the ALP, even if diplomatic duties earlier had forced him to be silent at times.

And by chance he happened to be ambassador to France handling negotiations with the Chinese there once Canberra had declared recognition of Beijing.

ALP followers were to boost Renouf as the man who had established relations with China when in fact the groundwork had been lain much earlier.

Whitlam also seems to have been taken in by Renouf activism and by the toadyism, foolishly, because it was to do much damage to his foreign policies later.

4. Deng Xiaoping and other Non-scoops

The Whitlam 1973 visit saw the usual round of dinners and talks. Perhaps the most remarkable event was the incognito appearance of Deng Xiaoping.

One day we all went off to see the Forbidden Palace. A small man wearing a cloth cap and a happy smile was showing us round.

Everyone thought he was supposed to be our guide for the day.

I looked a bit harder and realised it was none other than Deng Xiaoping, on yet another of his attempted comebacks from Cultural Revolution exile.

I asked him just that: “Are you Deng Xiaoping?”

He giggled agreement.

I felt certain I not only had quite a nice story to report for my paper, but also a worldwide scoop.

China-watchers around the globe were using Deng’s return as a measure of China’s return to sanity after the Cultural Revolution madness.

Sadly my story was cut to pieces by sub-editors in Sydney who, like the large group of Australian media people in the former palace, did not have the slightest idea who Deng was.

In fact, Deng had been prominent in the mid-sixties when, together with Zhou Enlai, he had tried to move China to more moderate policies.

He was to become even more prominent later.

5. The Mythical Mr Weidashping

Some time before our visits an employee of the Canberra Taiwan Embassy, a Mr Wang Wei-ping, had caused waves by seeking asylum in China.

In those days absconding, from freedom to communism, was supposed to be almost completely inconceivable.

I decided to try to track him down.

The authorities made him available for an interview, but he did not have much to say.

To save the one US$ a word cable costs (and to make sure at the other end they would realise I was sending a Chinese name) I wrote about my meeting with a Mr Weidashping.

But the paper the next day carried my allegedly scoop story with a Mr Weidashping.

Such were the joys of writing for the Murdoch media in those days.

(One of the worst of their sub-editorial boo-boos came during a Japan-Australia talkfest in Kyoto in 1974, where the head of the Australian delegation, Sir Edward Warren, went out of his way to tell me how he was going to be given the high Japanese award of the Sacred Treasure.)

(The story appearing in the paper the next day said he was going to be given the high Japanese award of the Secret Pleasure.)

6. Back to Australia, temporarily

The four-day Whitlam visit had been a tumultuous affair.

To cap it off, a RAAF VIP plane had been laid on to take him and all the rest of us back to Australia.

The plane would attempt something never before done – fly direct from Beijing to Canberra in one hop.

That would not be easy.

The plane needed much fuel to cover the distance, the Beijing runway was short, the journalists’ baggage was very heavy, and some of the journalists also were very heavy.

In the gathering dark of a late autumn evening, we just managed takeoff (I think I was the only one who noticed how close it had been).

The celebrations were already underway.

For the rest of the night as the party roared on, China and the rest of Asia slipped away beneath us. No one, not even Whitlam, pretended to try to sleep very much.

It had been a prime ministerial visit to top all prime ministerial visits.

3. The Cairns 1974 Trade Exhibition.

1. Chinese Ingratitude

2. Cairns Personality

For the 1974 exhibition Cairns had persuaded many Australian firms to spend a lot of money to bring their goods to China for display.

He even brought a model airplane – the Australian-produced Nomad.

1. Chinese Ingratitude

But the Chinese did little to help him.

They gave little sign of realising the political capital he had expended in organising the exhibition.

They not only purchased little. When the exhibition ended I discovered the Chinese were insisting the exhibitors had to take all their goods back to Australia.

Failing that, they had to hand over their exhibits to China for free or else pay good money for their disposal.

Needless to say, Cairns was not happy when I wrote that.

Later he was to make sure that I was not included in the press coverage for his next overseas trip (to Hanoi).

He chose a rightwing Singapore based reporter instead.

2. Cairns Personality

As I mentioned earlier, I had had dealings with Cairns back in the anti-Vietnam war protest days in Australia.

I had found him both very supportive at times and quite disinterested at others. This time too he remained as complex as ever— a hard man to get to know properly.

He was determined to see China as the leader of some great liberating revolution in Asia. Yet the shambles of the still lingering Cultural Revolution were visible on every side.

…

Our Beijing embassy was even less impressed by my reports, since it undercut badly their claims that Australia had a great trade future in China.

Which it was to have eventually, but not by selling Nomads.

As it turned out I was to discover the precursor of the great trade future myself —right in the middle of Beijing at that very moment.

As mentioned earlier, it was to be Australian iron ore to China