Chapter 20 – The China Book Emerges

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS and FOUR LANGUAGES

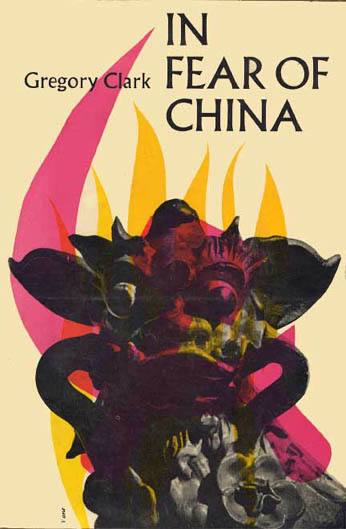

1. ‘In Fear of China’

2. The China Quarterly

3. Publishing Problems

4. Book Hegemony

5. Publishing Mistakes

6. More Book Reviews

7. ANU Books

8. Crawford’s Position

9. The Vietnam View

10. A Serious Reaction in Japan

Eventually the hard-cover book emerged.

Almost 400 pages of closely argued details – too closely argued maybe.

1. In Fear of China

I had called it “In Fear of China,” a title I still like.

With scrappy, voluminous material the publishers, Lansdowne Press, had managed to pull it all together into reasonable book form.

In Australia the book sold reasonably well – about eight thousand copies.

Ken Randall in The Australian had given it a good review, and it got into most of the libraries, where it can still be found.

But the main Sydney and Melbourne papers

determined to see China as a menace over-hanging Asia, managed to ignore the book completely.

That a nation which was using the China threat to conscript young men to kill Vietnamese and yet show no interest in the one book trying seriously to discuss whether that threat existed or not, was a measure of the intellectual and moral morass into which Australia had sunk.

Fortunately I could be found in most libraries – public and school.

…

Abroad it was much the same story.

Lansdowne had got a joint publication agreement with a UK publisher, The Cresset Press.

Some foreign academics got to notice it. But overall the reaction was muted.

2. China Quarterly

The one place where I had hoped the book would get a proper review was the China Quarterly – then the main outlet for studies by serious Sinologists.

But it got little more than a passing comment in its pages – much less than long essays about Chinese poets of the Han dynasty, for example.

The editor of the Review was David Wilson, my former classmate at the Chinese language school of Hong Kong University, and later to be made governor of Hong Kong.

Wilson was a UK government official and a thorough conservative. I knew it was unlikely he would like my revisionist view of China.

Even so, the fact that a UK Foreign Office official could be made editor of the Quarterly and avoid a serious review of a serious book on China critical of government policies was a major setback.

A reason I had written a book rather than a series of articles was the hope that I could drag some attention to my revisionist view of China in the Quarterly’s much-read book review pages.

That hope quickly died, and in the worst way possible.

Over a year of hard work struck dead in an editor’s moment.

3. Publishing Problems

True, it was still early 1968. The opinion-changing Tet offensive in Vietnam had yet to come.

China was caught up in its Cultural Revolution madness. Few were interested in a revisionist view of Chinese foreign policies.

In the foreword to the book I had tried to explain the Cultural Revolution as a power struggle between moderates and radicals for the post-Mao succession.

As it turned out, I think I was right.

But at the time the world preferred to see it as yet a further proof of Chinese insanity and militaristic instincts.

…

Another reason for choosing book form rather than article form was to show that there was a consistent thread running through Beijing’s various foreign policy problems, namely its efforts to contend with a rival regime in Taiwan and find its own place in the world.

Occasional problems were to be expected. But they were not proof of inherent aggressiveness.

On the contrary, in settling frontier disputes Beijing was often accepting quite generous solutions – to the point of leaving itself open to criticism attacks from the rival regime in Taiwan.

…

Taiwan was the key problem but there were others – the Sino-Indian dispute and the Sino-Soviet dispute in particular.

Pulling all that together required a book, I had thought.

Maybe I should have realised that Wilson (whom we had seen as something of an establishment dropout in the Hong Kong University language school) would lack the wit to realise there was important new material in the book.

Certainly his comments on the book in the Quarterly showed no sign of such understanding.

Ultimately, I suppose, it was also inevitable that a book by a little known author and put out by a little known publisher in a distant part of the world would do little to change global opinion.

I should have known that from the start.

4. Publishing Hegemony

That was part of the very large price we had to pay at the time for the hegemony of established US and UK publishers, and their authors.

The basic problem is still with us, even if the Internet has killed some of that hegemony.

But naively I had thought that if radically new and important information from a former China desk officer was out there, even if only between book covers of a little known publisher, people would feel some obligation to take account.

The incorrect understandings of both the Sino-Soviet dispute and the 1962 Sino-Indian frontier clash were to exert enormous influence on the policy makers for decades.

I had already discovered one example earlier, sitting with Paul Hasluck in the Kremlin in 1964.

Conclusion: If you want to sell a book in Australia, write about Australia.

And very little less.

5. Publishing Mistakes

In retrospect, I had also made a serious mistake in getting myself published in book form.

The book had two important additions to knowledge about China – knowledge I had gained from my position within the foreign affairs bureaucracy, and by some difficult reasoning.

One was the inside story of the 1962 Sino-Indian frontier conflict.

The other was the the research I had made into the origins of the Sino-Soviet dispute.

I should have got them published separately as articles, ideally in China Quarterly.

Even biassed editors would have found it had to reject the information in article form.

Both when published in the Quarterly could have made a strong impact on the conventional wisdom about both topics – conventional wisdom which was to be largely responsible for dragging the world into the Vietnam and other anti-China hysterias.

But being published in book form and buried inside a mass of other material, they could be ignored – at least by someone like Wilson.

It was a mistake which will stay with me for a long time.

Much of the other material in the book was available from other sources. I was using it to back up my argument China was non-aggressive, that Taiwan was the main focus of Beijing’s policies.

But I could have left all that to others to discover and point out.

Instead, by trying to pull together the entire framework of China’s policies to reach these conclusions I was to spend a lot of time and effort which should have been used in other directions.

I was also to impose an unfair burden and distraction to R’s life.

I was to bury my two main contributions in a mass of other less important history and detail.

6. More Book Reviews

In Australia the one serious academic review I got was from Peter King of Sydney University, who praised the analysis of the Sino-Soviet dispute (but made the usual complaints about the fate of the Tibetans).

Against that was a vicious review from J.D.B.Miller, head of the ANU International Relations Department.

While admitting that it was a serious book (earlier either he or someone in his department had told the ANU Press that my manuscript was a useless, pro-Beijing tract), he then slammed me on what he called three crucial points of fact:

1. my claims that the CIA had been involved in the 1965 massacres of pro-communist and leftwing Indonesians

2. that it was India that had provoked China in the 1962 border dispute,

3. that the Taiwan problem was the focus of Chinese foreign policy.

I leave it to the reader to decide who has been proved right by history.

7. ANU Books

At the time Miller’s ANU department was using the ANU Press to get its own literature into print, much of it anti-Beijing.

Few of the tracts they produced survive in any shape or form today, even in public libraries.

Perhaps the most portentous was a book urging the Cold War idea of an Indian, Australian and Japanese joint anti-China alliance.

ANU’s Crawford was a firm supporter of the idea.

One of the book’s authors managed to accuse China of Han chauvinism for wanting to reunite with Taiwan.

Clearly he did not know that the bulk of Taiwan’s population was in fact almost entirely Han Chinese – migrants from China’s nearby Fujian province a few centuries earlier and who still spoke the Fujian dialect of Chinese.

The ANU and Crawford were so proud of this wretched book that they had leaned on Japan’s then Foreign Minister, Miki Takeo, who was visiting Australia at the time, to join in a big book-launch ceremony.

The sight of Miki, a genuine internationalist who had opposed Japan’s militarists during the war and had long advocated better relations with China, being dragged in to endorse this Cold War, anti-China tract, the contents of which he obviously knew nothing, was less than edifying.

8. Crawford’s Position

Crawford’s political position deserves some mention.

Some have argued that he was a genuine liberal, mainly because he had been willing in the Cold War years to defend some alleged pro-communists from government attacks – one was the economist Helen Hughes whom I was to get to know well later.

But he clearly had a very different view of me after I had come out against the Vietnam War, despite my having no communist or any other leftwing connections.

Crawford’s position was typical of what I call the Kennedy Liberals — progressives who realised European communism deserved some kind of understanding but with only a superficial knowledge of Asian communism.

So they not only saw the Asian version of communism as some kind of Hitlerian monster, they felt by criticising it they could balance their political appearance.

By criticising Asian communists they got the credentials that allowed them to avoid having to make total condemnations of European communists

Unfortunately for me, the distorted view of China was to be even stronger in Australia than in the rest of the Western world— at least until China became the flavour of the month some years later.

But by then my efforts over Vietnam and to explain China were a distant memory.

9. The View from Vietnam

Years later I managed to get myself invited to an official Hanoi event to mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of Wilfred Burchett – the one Australian who did so much to tell the world about the Vietnam tragedy.

I rather foolishly tried also to get some recognition for the efforts of our anti-Vietnam War movements in the West, and possibly even for myself.

The response? ‘Yes, we in Vietnam were aware of what you anti-war people in the West were doing.

‘But while you were writing and talking we were being bombed and dying every day.

‘And ultimately it was only through those efforts and sacrifices on the ground that the war did in fact end as it did.

‘The one Australian who was on the ground with us and suffering with us was Burchett, which is why we respect him so much.’

I should add that precisely for those reasons he was despised by the pro-war people in Australia.

Burchett’s fate at the hands of Australia’s generally conservative media and officialdom was a major reason I was later to decide I had no future in that country without a conscience.

10. A Serious Reaction in Japan.

Fortunately it was in Japan, where the China topic was being treated seriously, that my book got to be treated seriously.

Matsumoto Shigekazu, the Ajiken researcher on Chinese affairs, was determined to translate the book into Japanese and have it published by Ajiken.

The Japanese version appeared in 1969 under the title of Kokusai Seiji to Chugoku – International Politics and China.

The translation was less than perfect. But it put me on the map in Japan and was later to be fairly crucial in my deciding on Japan rather than China for a career.

One of Japan’s top scholars on China, Nakajima Mineo, was later to tell me how my theory about the 1958 Taiwan Straits crisis underlying the Sino-Soviet dispute of the early 1960’s provided a major break-though in his own thinking about China.

Later, in 2002, Nakajima would invite me to help him set up an international university in Akita, in northern Japan – a university that in just ten years would come to be seen on a par with most of Japan’s top universities.

But I am getting ahead of my story.