THE SINO/INDIAN DISPUTE

THE SINO/INDIAN DISPUTE

An outline of the Tibetan question is needed to understand the very important role that country has played in Sino/Indian relations.

India had, on gaining independence in 1947, inherited the British “special position” in Tibet, along with the Mission in Lhasa and trade agencies in larger towns. It had retained the services of British officials stationed in Tibet. When, in 1949, Tibetan leaders made their bid to contact foreign Governments, they first contacted these officials, and it was only a short step for the suspicion-minded Chinese to regard this as evidence of Indian collusion with the British.

The Chinese also had ideological reasons for believing there was collusion. At the time they came to power, Moscow was propagating the line of a world divided into two camps, with the Indian Government depicted as a tool of British imperialism and firmly situated in the opposing camp. The Communist Chinese leaders, who previously had had little contact with the outside world, faithfully repeated these accusations against Nehru and his Government.

After the Chinese occupation of Tibet in late 1950, Beijing’s suspicions of the Indians were further aroused when Nehru, in notes to the Chinese Government, expressed the “surprise and regret” of his Government at the Chinese action. He described as “deplorable” the Chinese use of force in Tibet.1

The Indians justified their criticism of the Chinese on the ground of their special interest in Tibet, from which the Chinese inferred that the Indians were implying some restriction on Chinese sovereignty. A sharp reply was received from the Chinese accusing the Indians of unwarranted interference and claiming that the policy of the Indian Government was “affected by foreign influences hostile to China in Tibet”.

Nevertheless, whatever suspicions the Chinese may have felt about the Indians in 1949-50 must have been eased somewhat by subsequent developments. India opposed the 1950 Tibetan appeal to the United Nations; it was one of the few non-communist countries not to condemn China’s intervention in the Korean War; it sought to have China seated in the United Nations. Then came the signing, in April 1954, of an agreement by which India recognised without qualification China’s sovereignty over Tibet and conceded many of India’s former rights there. A few months later the Chinese Premier, Chou En-lai, paid a successful visit to India, and in October of the same year Nehru visited Beijing.

The very considerable improvement in Sino/Indian relations from 1950 to 1954 was on the Indian side almost entirely the result of efforts by Nehru, who saw friendship between China and India as the starting point of a new order in world affairs. But the Chinese must have realised that considerable opposition to Nehru’s pro-China policies, at least as far as Tibet was concerned, existed both within and outside the Indian Government. It should also have been clear that problems were going to arise over wide discrepancies in the claimed Sino/Indian border, as shown in maps published by both sides.

However, as long as Nehru’s China policy appeared to produce results, his opposition in India remained silent. It was important for both Nehru and the Chinese that this policy continued to appear to give results, and hence the efforts made by both sides to keep intact the framework of good relations. The Chinese, under the 1954 agreement, allowed India to maintain certain trade and pilgrimage rights in Tibet. They sought to play down the significance of border differences, stating that they had simply inherited their claimed Sino/Indian frontier from the pre-1949 Nationalist Government and that it would be “revised” in due course.2 Nehru, for his part, avoided public mention of the reality and extent of border differences, and it seemed that both sides were moving towards a compromise settlement of the question.

What were these differences, and what evidence was there that both sides were in fact prepared to compromise?

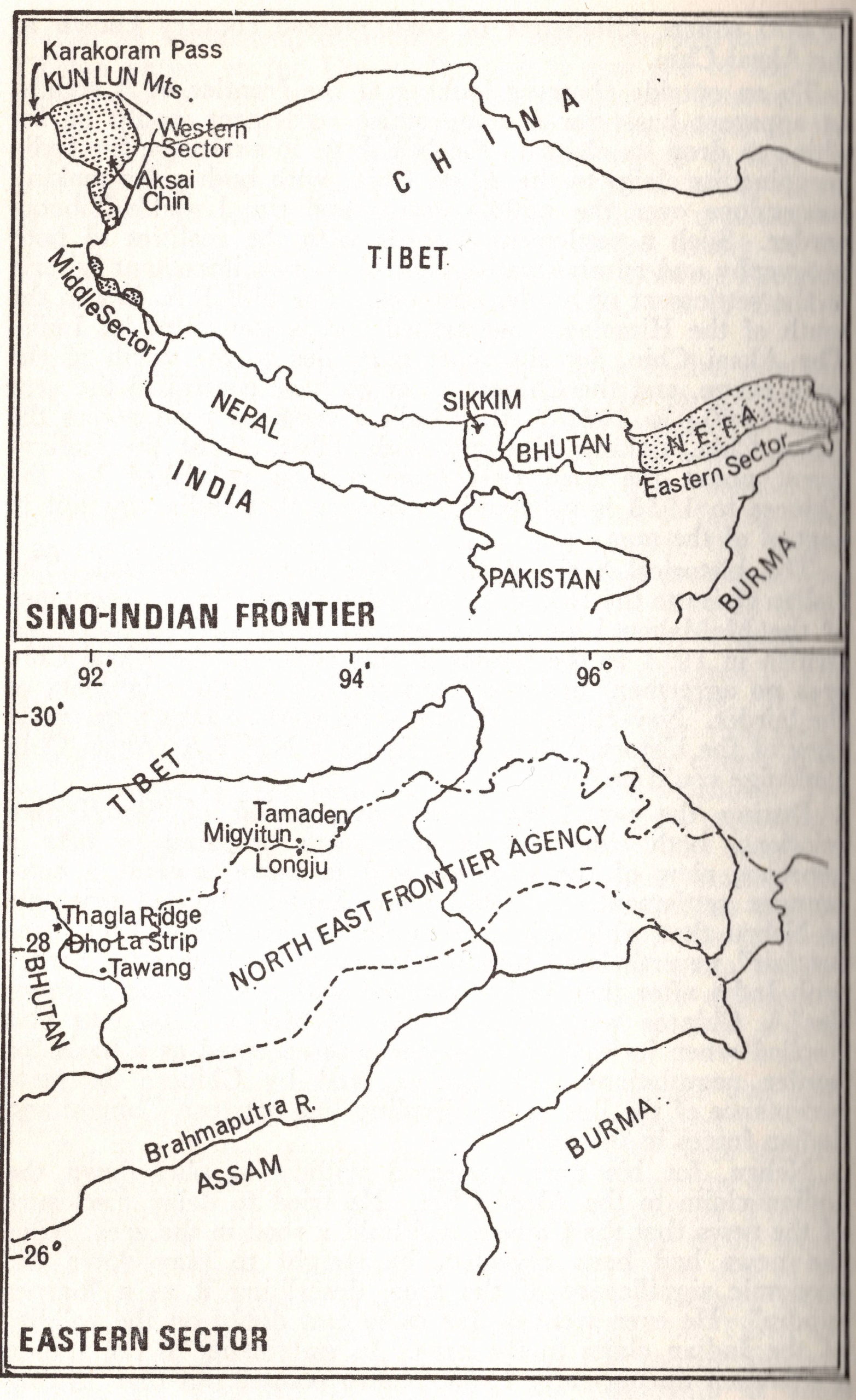

The Sino/Indian border can be divided into three sectors:

(i) an eastern sector where 99,000 square kilometres of territory described by the Indians as the Northeast Frontier Agency, or N.E.F.A is in dispute: (ii) a middle sector where some 2.000 square kilometres of territory on either side of the main Himalayan passes is disputed: and (iii) a western sector where the Indian province of Ladakh borders on Tibet and Xinjiang and where both the Indian/Tibet and Indian/Xinjiang borders are disputed, in particular the ownership of some 30,000 square kilometres of high plateau country known as the Aksai Chin.

To an outside observer looking at the frontier as it stands, a basis for a compromise settlement would be for China to drop its claim to the N.E.F.A. in exchange for India dropping its claim to the Aksai Chin, with both sides making concessions over the middle sector and the Ladakh/Tibetan border.

The N.E.F.A. lies to the south of the Himalayan watershed and is controlled by India though some of the population is of Tibetan origin, in the Tawang area especially where there is a Tibetan pilgrimage temple. The Aksai Chin, for the most part, lies to the north of the main range, but the Chinese claim to have controlled the area since 1950. In 1956-7, they built a strategic road across the Aksai Chin, linking Xinjiang with Tibet. That the Indians only learnt about the road from a map published by the Chinese in 1958 is substantial evidence that India was not in control of the area.

The historical basis of the border is confused. The Indian claim to the N.E.F.A. rests almost entirely on acceptance of the McMahon Line, a line agreed to by the Tibetans and British in 1914 as the border in this area. In the Aksai Chin area no agreement has ever been reached about the border. Nevertheless, if both sides were to take a generous view of the historical data, a basis for a N.E.F.A./Aksai Chin exchange could be found.

During the post-1954 honeymoon period of Sino/Indian relations, both sides did in fact seem prepared to take a generous view of the situation and to move towards a compromise settlement. In 1956, Chou En-lai admitted privately to Nehru that, although he thought the McMahon line “was not fair”, nevertheless China would accept the line as the border with India after they had “consulted with the Tibetan authorities”.3

Chinese recognition of the McMahon Line was also implied when its eastern extension was accepted as a basis for border negotiations with Burma, and by Chinese de facto acceptance of the line as the dividing line between Chinese and Indian forces in the area.

Nehru, for his part, appeared willing to play down the Indian claims to the Aksai Chin. He tried to delay disclosure of the news that the Chinese had built a road in the area. After the news had been revealed, he sought to play down the economic significance of the area, describing it as a “barren tundra”.

He even went so far as to cast doubt on the validity of the Indian claim to the area. In statements to the Indian parliament during early 1959, Nehru pointed out that “during British rule, this area was neither inhabited: nor were there any outposts”, adding that “this place, Aksai Chin area, is distinguished completely from other areas. It is a matter for argument which part belongs to us and which part belongs to somebody else. It is not clear”.

Nehru’s efforts to take the heat out of the Aksai Chin question were not entirely successful. (One of his critics even suggested building an atomic reactor in the area to promote its economic development.) News of the Chinese road in the area appeared to trigger off long-suppressed Indian sensitivity over the border issue, and in August, 1958, the Indian Government made a formal claim to the disputed territory in all three sectors.

In a letter to Nehru of January,1959, Chou En-lai claimed that the Aksai Chin was Chinese territory and added that the McMahon Line was a “product of British aggression”, illegal, and had “never been recognised by the Chinese Central Government”. He proposed that the existing status quo be maintained, however, pending a negotiated settlement of the dispute, and added that China would take a “realistic attitude” over the McMahon Line.*

*The Indians have since claimed that Chou’s 1959 denunciation of the McMahon Line represented an about-face in his attitude as expressed in 1956. Once the Indians had lodged a formal claim to ail the territory in dispute, however, it was only to be expected that the Chinese would move to establish the basis of their claim in the N.E.F.A. and so provide a bargaining counter against the Indian claim to the Aksai Chin. Moreover, it is difficult to see any significant difference between the Chinese 1956 and 1959 positions.

The CIA-backed Tibetan uprising of March,1959, upset the delicate balance of Sino/Indian relations. Reports of Chinese military action to suppress the uprising, together with the sight of thousands of Tibetan refugees crossing into Indian territory, quickly aroused feelings of alarm and anger in India, particularly among those who believed their country had an historic interest in Tibet. Nehru’s rightwing critics charged that India should never have allowed the Chinese into Tibet in the first place. Nehru, influenced possibly by the emotional strength of Indian public opinion, came out in open condemnation of Chinese behaviour in Tibet.

The Chinese reacted even more strongly than they had in 1950. Nehru, in addition to condemning the Chinese, had spoken of his sympathy with “the aspirations of the Tibetans for autonomy”. He had given asylum to the Dalai Lama, who was also allowed facilities to make his 1959 appeal for U. N. action over Tibet. And the Chinese had good reason to believe that the Tibetan guerrillas were receiving arms from across the Indian border.4

In May,1959, the Chinese published a long article urging, almost begging, Nehru not to be swayed by his reactionary rightwing critics and to return to the path of Sino/Indian friendship. With a frankness and detail probably unmatched by any other Chinese statement on foreign policy, the article set out the Chinese case over Tibet, and accused the Indians of unjustified interference. Indian trade with Tibet was greatly restricted. Clashes involving casualties occurred at several points along the disputed border as the Chinese Army extended its control over border areas in an effort to restrict the movement of Tibetans across the frontier.*

*Whether the sites of these clashes lay in Chinese or Indian territory has been argued at some length. At least one of these sites, however, Tamaden, lay to the north of the McMahon Line, clearly within Chinese territory, and was subsequently evacuated by the Indians.

These border clashes, following in the wake of the Tibetan uprising, appeared to put an end to Nehru’s willingness to compromise over the border dispute. Having earlier in 1959 cast doubt on the Indian claim to the Aksai Chin, in September he told the Indian Parliament that the Chinese claims were “absurd” and would mean “handing over the Himalayas to them as a gift”.

A Chinese call in November 1959 for negotiations and a twenty-kilometre military withdrawal from the McMahon Line in the east and the “line of actual control” in the west to prevent a recurrence of border clashes was met with an Indian demand for a prior Chinese withdrawal from the Aksai Chin. A Chinese reply pointing out that this should also be paralleled by an Indian withdrawal from the NE.F.A. was ignored. In the end the Chinese appeared to settle for a freezing of the existing status quo – without negotiations or a twenty-kilometre withdrawal.*

*The Chinese claim to have made a unilateral twenty-kilometre withdrawal, leaving only civilian-manned posts along the line of actual control.

However, if the Chinese were happy to keep things as they were (keeping also their road across the Aksai Chin), Nehru and his Government were not. Throughout 1960-61 Indian opinion progressively hardened, and demands for the Government to do something about Tibet and the disputed border increased. The army was given full control over the frontier districts and it proceeded to build up its strength in these areas.

During the summer (northern) of 1962, Indian military patrols repeatedly crossed the Chinese-claimed line of actual control in the western sector of the frontier. Posts were established well behind the Chinese forward positions in territory claimed and occupied by the Chinese. Frequent and insistent Chinese protests were met with the bald statement that the Indians were merely operating in Indian territory. By August 14, Nehru was able to announce that India had three times as many posts in the western sector as the Chinese. He asked for a free hand to continue the build-up of Indian strength in the area.

The Chinese had repeatedly warned that a continuation of such activity would end in hostilities. On July 9, they had warned the Indians “to rein in on the brink of the precipice”. On August 4, they called for immediate negotiations on the border. The Indians replied that negotiations could not be held until the Chinese had ceased their occupation of “every square inch of sacred Indian territory”, and that the Chinese must first “vacate their aggression” in the Aksai Chin. The Chinese replied on September 13 proposing talks to begin on October 15 “without preconditions”, that is, without a Chinese withdrawal from the Aksai Chin. The Indians refused the offer.

While Indian military pressure was building up along the Chinese-claimed border in the western sector, a curious situation was developing along the McMahon Line in the eastern sector. The Indians claim that at its western end, the McMahon Line was not accurately drawn: that it was meant to have followed the crest of a line of hills known as the Thag La ridge.

The Chinese claim, and have produced the original McMahon Line from the Tibetan archives to prove their point, that the line as originally drawn lies approximately twelve miles south of this ridge along the southern side of a small river valley. (Western maps show the McMahon Line in conformity with the Chinese claim.) The area between the Indian and Chinese versions of the McMahon Line is described by the Indians as the Dho La strip.*

* This was not the only unilateral revision of the McMahon Line carried out by the Indians. In his letter to Chou En-lai of September 29, 1959, Nehru admitted that in the Migyitun area (to the east of the Dho La strip) the border shown on Indian maps “differs slightly from the boundary shown in the Treaty map”. He claimed that when the McMahon line was drawn, “the exact topographical features in this area were not known”. The Indians have also now come to admit that “blind adherence” to the original McMahon Line would leave the Dho La strip on the Chinese side at the border.7

It is not clear who first occupied the Dho La strip. The Chinese claim that the area had always been under their control and that Indian troops moved in during 1962. The Indians claim they had long occupied the area and that the Chinese began a to establish posts in the area after September 8, 1962. What is clear is that on October 12, 1962, Nehru announced in the Indian Parliament that he had given the order to drive the Chinese out of the Dho La strip.

Eight days later, on October 20, the Chinese attacked in force across the Thagla La ridge and into the disputed strip, while advancing their troops into the Chinese-claimed territory in the western sector where the Indians had earlier established posts. Four days later, the Chinese called for a ceasefire to be followed by a withdrawal of both sides from the line that separated them at that moment (the so-called October 24 line of actual control).

Failing to get a satisfactory response from the Indians, the Chinese advanced troops south of the Dho La strip into the N.E.F.A., defeating Indian military forces in the area (though with less success in the Aksai Chin area, according to Indian sources). Two weeks later, they withdrew to the positions occupied on October 24.

The dispute between the Chinese and Indians ever since has been whether the Chinese should maintain their October 24 positions or withdraw further to the positions they occupied before fighting broke out.

Sino/Indian Hostility: a Case Study in Mutual Misunderstanding.

The Chinese attack of October 20, 1962, has led to an almost complete breakdown in relations between the two countries. The level of each country’s diplomatic representation in the other has been greatly reduced. Many thousands of Chinese nationals have been expelled from India. The few Indian nationals living in China have, in one way or another, been forced to leave.

Border incidents have continued. Both sides have launched extreme propaganda campaigns against each other, the Chinese denouncing Nehru as a representative of the “big bourgeoisie” and a tool for U.S. aggressive designs against Tibet, while the Indians denounce the Chinese for having aggressive, imperialist designs against Indian territory. Both sides have tried hard to discredit each other internationally. Both sides have increased their military preparedness along the Himalayan frontier, particularly India, which has doubled its military budget to a level it cannot afford.

Who is primarily to blame for the breakdown in Sino/Indian relations? Both sides realise that they have somehow or other to explain why the other side suddenly, in 1959, decided that its interests were no longer served by the maintenance of normal relations. The Indian explanation is that Chinese pre-1959 policy was designed to lull India into a false sense of security and so facilitate Chinese ambitions. The Chinese explanation was that reactionary elements began to gain the upper hand in the Indian Government in 1959, and point to the post-1959 increase in U. S. aid to India as evidence.

The Chinese had in fact made their first hostile move against the Indians back in 1959 when they restricted Indian trading and other rights in Tibet. The Chinese had also, according to the Indians, extended somewhat the area they claimed in the western sector.* And they had, according to the Indians, been responsible for the 1959 border clashes already mentioned.

*The Indian charge is based on alleged differences between the frontier claimed by the Chinese to 1956 and that shown on a map of the claimed Sino/Indian frontier handed to the Indians by the Chinese in 1960. The Chinese deny any difference between the two lines.

The hardening of the Chinese attitude towards India in 1959 was clearly related to Tibetan developments in that year. Was sensitivity over Tibet was sufficient to justify this hardening of attitude?

To accept that the Communist Chinese are, in fact, extremely sensitive over Tibet does not imply a simple acceptance of Chinese propaganda. If all non-communist Chinese believe that China has the right to consider Tibet as an integral part of her territory, we should accept that Communist Chinese are equally convinced.

Nor may it be so absurd for the Communist Chinese to think along these lines. If the British had earlier convinced themselves that the activities of one Russian agent in Lhasa could lead the politically unstable Tibetans to ally themselves with Tsarist Russia, the Chinese could be excused for thinking that the presence of a British Mission in Lhasa dealing directly with the independent-minded Tibetans was suspicious.

CIA support, or even encouragement, for the 1959 uprising was serious challenge to Chinese ownership demanding an answer. Finally, the Chinese were bound to be impressed by the demands of the Indian rightwing for action against the Chinese in Tibet.*

* For example, some weight could be attached to the fact that the then Chief of the Indian Army Staff wrote an enthusiastic foreword for a book published in 1961 entitled The Chinese Aggression. The author of the book, a Dr. Satyanarayan Sinha, predicted that the “clash of the Indochinese weapons for the possession of the Himalayas will lead to making Tibet an independent country again”, and suggested ways in which this could be done.

Other reasons for believing the Chinese may be sensitive about Tibet include the way British officials captured in Tibet in 1950 were subjected to long imprisonment and continual interrogation – treatment far more severe than that given to British nationals who fell into communist hands elsewhere in China. And there was Nehru’s sad admission to the Indian Parliament in 1959 after talks with Chou En-Iai, of the Chinese having “some sort of kink in their minds… of foreign countries, United Kingdom or America, somehow making incursions into Tibet”.

By 1962, the Chinese were confronted not only by Indian agitation over Tibet, but also by two further aspects of Indian behaviour which could even more easily have been misunderstood. They were: (i) the Indian military build-up along the Sino/Indian border in 1961-2 and (ii) rigid Indian insistence that, as a precondition to border negotiations, the Chinese must first evacuate the whole of the Aksai Chin.

At the time, the Indians justified their position on negotiations and their military build up in terms of the correctness of all their border claims. But was this the case?

Until the 1920’s, the region now known as the N.E.F.A. was largely unexplored. It was, and still is, inhabited by tribes of Tibeto-Burmese origin, some of which enjoyed trade and tributary relations with Tibet. Certain areas in the north of the region, the Tawang district for example, were not only inhabited by Tibetans but were under administrative control from Tibet.

The McMahon Line was negotiated with the Tibetans in 1914 at the time of the Simla Conference. It was drawn as far to the north as possible, since the British at the time sought to forestall a feared Chinese expansion into the foothills bordering the Assam plains. The Tibetans, as mentioned in the previous chapter, accepted the McMahon Line as part of a bargain whereby the British would press the Chinese to concede territory elsewhere to Tibet.

Even so, the Tibetans were not entirely happy about losing territory south of the McMahon Line, the Tawang district in particular. Their acceptance of the line was conditional on possible future adjustments in their favour. No such adjustments, were ever made.

The British also failed to extract the promised concessions from the Chinese, since the latter refused to accept the Convention produced at the Simla Conference. Thus, even as a Tibetan/British frontier, the McMahon Line does not have full validity, particularly as the Tibetans subsequently, in 1936, made a formal request to the British for revision of the line in their favour – a request which the British ignored.

As late as 1946, the Tibetans were still collecting taxes in the Tawang area. In 1947, the Tibetans approached the newly established Indian Government, seeking the “return” of “Tibetan territories” from Assam to Ladakh*8.

The Indians replied archly: “The Government of India should be glad to have an assurance that it is the intention of the Tibetan Government to continue relations on the existing basis until new Agreements are reached . .. This is the procedure adopted by all other countries with which India has inherited Treaty relations from His Majesty’s Government”.9

…

The validity of the McMahon Line as a Chinese/Indian frontier even more doubtful. True, in rejecting the draft Simla Contention, the Chinese did not specifically object to the McMahon Line as drawn on the map of Tibet attached to the Convention. But as the Chinese point out, the then Chinese Government had no way of knowing what this line was supposed to represent, since the terms of the McMahon Line agreement were for some reason kept secret by the British and Tibetans until 1929.

It could, in theory, have been a border between Tibet and a Chinese-owned N.E.F.A. Moreover, Chiang Kaishek’s Government was later to make it clear to the British (and the Indians after 1947) that it did not accept the McMahon Line. The Chinese have also pointed out that, since neither the British nor the Chinese regarded Tibet as a sovereign entity, the Tibetans were obliged to obtain Chinese approval for any frontier negotiated with a foreign power. * Failure to obtain this approval, both at the Simla Conference and later, meant that the McMahon Line never at any stage enjoyed international legality.

And finally, as the Chinese never tire of pointing out, many Western and Indian maps, including one reproduced in a book by Nehru himself, Discovery of India, have even in recent years shown the Sino/Indian border as running along the edge of the Assam plain, in conformity with the traditional Chinese claim.

*The 1906 Convention between Britain and China had required China to accept responsibility for Tibet’s foreign relations. The 1907 Anglo/Russian Convention required Britain ‘not to enter into negotiations with Tibet except through the intermediary of the Chinese Government’. Negotiations with the Tibetans over the McMahon Line were thus a breach of both conventions – a possible reason why the terms of the McMahon Line agreement were kept secret.

For the Communist Chinese to appear to be willing to drop their N.E.F.A. claim is no small concession in view of the very considerable doubts as to the validity of the McMahon Line. Indeed, the Nationalist Government in Taiwan feels so strongly about the justice of the Chinese clams that its official newspapers have accused Beijing of being willing to abandon “sacred” Chinese territory. They have predicted that the present Communist Chinese leaders will be condemned by future generations of Chinese for their betrayal of China’s interests.

Nevertheless, the Indian position was that the Chinese should not only drop their claim to the N.E.F.A. but to the Aksai Chin also. How strong is the Indian claim in the western sector of the disputed frontier?

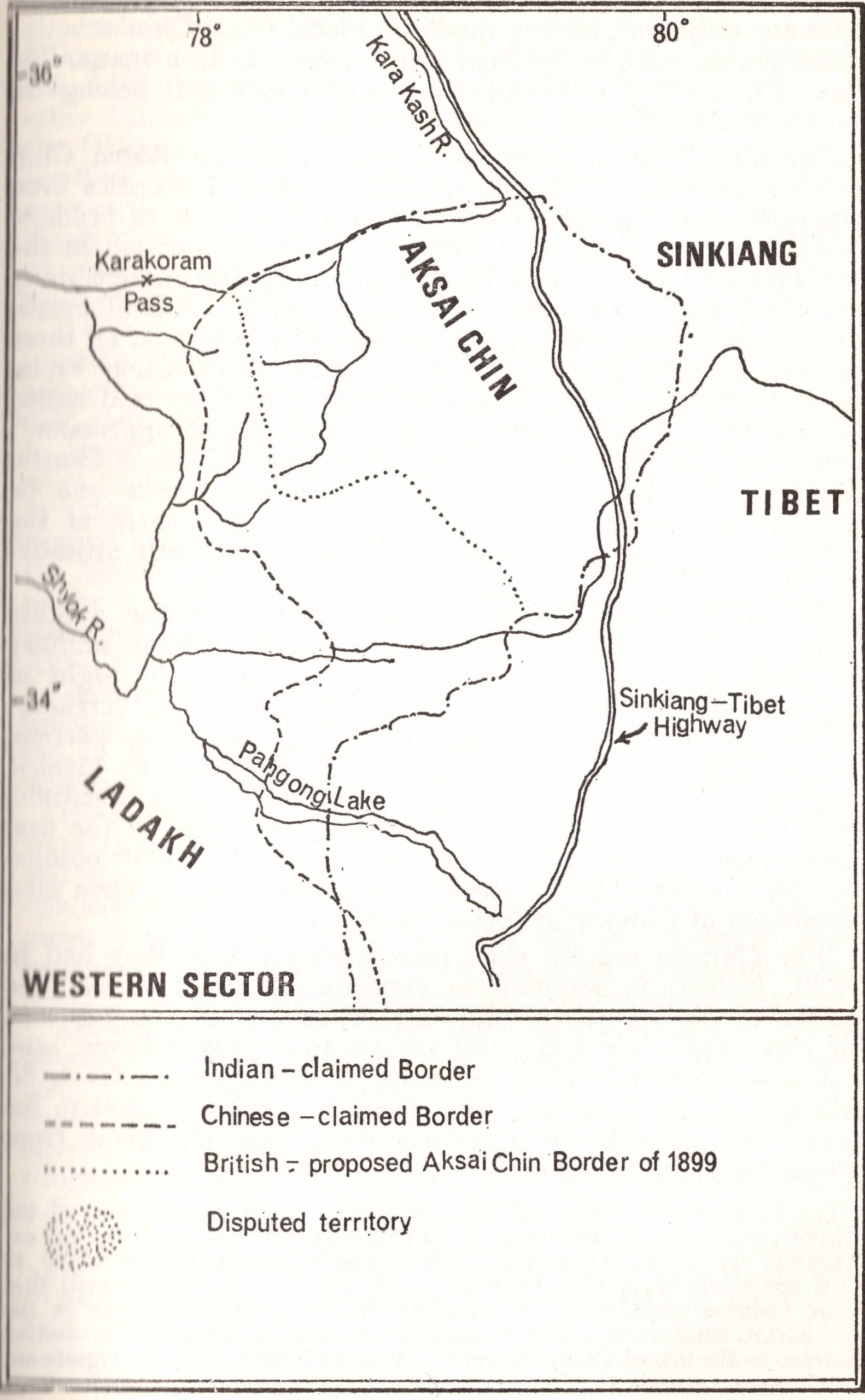

The province of Ladakh, which lies on the Indian side of the disputed western sector, was originally a semi-independent state which had a complex tributary relationship with Tibet. It was far from being clearly defined Indian territory. These links with Tibet were severed as a result of the 1841 invasion of Tibet from Kashmir, and Ladakh was incorporated into India. In the agreement which followed the invasion, the Ladakh/Tibet border was defined simply as following “the old established frontier”, and it was only subsequently that British cartographers decided where this frontier should lie. A small area lying between the Chinese-claimed and Indian-claimed frontiers is in dispute.

By far the larger area in dispute, the Aksai Chin, lies for the most part north of the Ladakh/Tibet frontier, and its ownership depends on a definition of the Ladakh/Xinjiang border. At the end of the nineteenth century, the British decided an effort should be made to define this border, and in 1899 a note was delivered to the Chinese suggesting a possible alignment. (This alignment is shown on the map above, and it will be seen that it leaves with China much of the territory at present in dispute.)

The Chinese never replied to the note. Shortly afterwards, the British attitude changed. Alarmed by growing Chinese weakness in Central Asia, and fearing Russian expansion into the area (fears similar to those being entertained in connection with Tibet), the British felt they should establish the border as far north as possible to forestall any southward advance by the Russians. British maps began to show the border as lying far to the north along the Kun Lun mountains.

Chinese agreement was never sought for this claimed border (despite the fact that the British recognised Chinese sovereignty in Xinjiang) ; presumably it was only being put forward as an emergency measure in case the Russians attempted to seize Xinjiang. By the 1920’s the Russian threat had disappeared, and it was deemed safe to drop this particular claim.

In subsequent years, British and Indian maps showed a variety of claim lines some coinciding with the present Chinese claim line, some the claim line along the Kun Lun mountains, and some an in-between claim line which ran south of the Kun Lun mountains but which included the Aksai Chin as Indian territory. Maps showing this last claim line were in general use at the time of the 1947 transfer of power, and appear to constitute the basis of the present Indian claim to the Aksai Chin. However, the only border to have ever been officially proposed to the Chinese by the British in this area was that of 1899, and, as already mentioned, this border left most of the Aksai Chin with China.

Whatever the merits of rival Chinese and Indian claims to the Aksai Chin area, it does seem clear that the Indians can hardly speak of the frontier they claim in this area as being already defined by history and therefore subject only to demarcation. In this connection a rather curious aspect of the Indian position should be mentioned – an aspect which has been overlooked by most students of the Sino/Indian dispute.

Numerous Indian authorities, including Nehru himself, have claimed historical validity for their version of the Indian-Xinjiang frontier on the ground that the line proposed by the British in 1899 “ran along the Kun Lun range to a point east of 80° longitude, where it met the eastern boundary of Ladakh”. In fact, the 1899 line ran well to the south of the Kun Lun mountains, and the text of the proposal speaks only of the line meeting “the spur running south from the Kun Lun range, which [the spur] has hitherto been shown on our maps as the eastern boundary of Ladakh. This is a little east of 80° east longitude”.*

A misquotation of these dimensions is rather serious, particularly when it is used to justify an official claim to some 30,000 square kilometres of territory, and when, on the basis of this claim, negotiations are refused in favour of a military solution of a complex border dispute.

*The only observer who appears to have noted this misquotation is Alastair Lamb. In his book, The China-India Border, he gives the full text of the British note of 1899 and lists some of the Indian authorities who have misquoted the 1899 proposal. Distribution of his book within India has been banned.

It would seem, therefore, that an impartial observer who takes into account not only the historical background of the border dispute, but also the equally relevant criteria of geography and administrative control, would agree that the Chinese are not being unreasonable when they call for border negotiations on the basis of the present status quo.

If, as seems to be the case, the Chinese are prepared to do a N.E.F.A./Aksai Chin exchange leaving India in control of far the largest and most valuable of the territories in dispute, our observer may even feel that the Chinese are being quite generous. And if our impartial observer were to reach such a conclusion, it seems highly likely that the Chinese would be convinced of the reasonableness of their position and the unreasonableness of the Indian demand for a unilateral Chinese withdrawal from the Aksai Chin.

If the Chinese were in fact convinced that they were in the right over the border dispute, they would in all probability have interpreted the Indian military build-up along the disputed border in 1961-2 as evidence of active hostility. Striking confirmation that this was the case is contained in the “Tibetan Documents” – official Chinese documents which were captured by Tibetan rebels in 1961 and which subsequently found their way to the U.S., where they have been translated and published.

These documents were intended as background briefing to senior Chinese military commanders stationed along the Sino/ Indian border. As such, their contents cannot be dismissed simply as propaganda. The documents warned of U.S./Indian collusion to build up pressure along the Tibetan frontier as a prelude to a joint attack against Tibet. Military commanders were instructed to observe strictly the twenty-kilometre troop withdrawal from the line of actual control and to avoid clashes with advancing Indian patrols since this would provide the “imperialists” with the pretext they needed to justify their planned attack.*

*This instruction, incidentally, could explain why in the months before October 1962 the Chinese took no military action to prevent the incursions of Indian patrols along the western sector. The Chinese attack of October 20 could thus he interpreted in much the same terms as the 1950 Korean intervention – as a carefully considered resort to force to deter a feared enemy from further advance, taken only after repeated warnings had failed to deter his advance.

Were the Indians themselves convinced of the reasonableness of their position?

To understand the Indian position we need to take account of the intensely emotional nationalism which underlies Indian border policies. Even before 1959 Nehru was being strongly criticised for his apparent refusal to take a hard line with the Chinese over Tibet and the disputed border. After 1959, Nehru may have felt that he had no choice but to take an uncompromising stand towards China if he was to prevent the Indian rightwing from exploiting nationalist passions which had been aroused throughout the country. And he had himself suffered a serious blow to his own prestige.

Thus it is possible to conclude that Indian behaviour throughout 1961-2 was influenced by a sense of wounded nationalism and wounded pride, which in turn were a reaction to the events of 1950. If we can assume that Indian behaviour was emotionally based, we have a ready explanation of its seemingly unnecessary rigidity.

To observers of Sino/Indian relations in the period prior to October 1962 (of which the author was one), it seemed highly likely that the Indian policy of military pressure along the disputed border, together with intransigence over the Aksai Chin and the Dho La strip, would inevitably provoke a Chinese military response in which the Indians could be the only losers.

That Nehru and his advisers had seriously mis-assessed the probable Chinese reaction to Indian policies and that this mis-assessment was at least partly a result of the emotional manner in which they had reacted to previous events, has been recently confirmed. The former Commander of Indian Military Forces in the N.E.F.A., Lieutenant-General B. M. Kaul, in a book entitled ‘The Untold Story’ and published in 1966, has given some of the background to events of 1962.

Kaul states that Nehru believed the 1959 revolt in Tibet indicated a “break in the morale of the Chinese people and armed forces and that if India dealt with the Chinese it would get the better of them”. *10

Kaul also states that the Indian Government decision to move against the Chinese in the Dho La strip was made on September 22, and by way of explanation adds: “Nehru and his Government were deeply concerned about public opinion which was worked up at the time”. The decision was queried by the Army Chief, General Thapar, who on October 2 warned that the use of force against the Chinese was bound to have serious repercussions. Nehru assured Thapar that “he had good reasons to believe the Chinese would not take any strong action against us”.

Kaul adds that on October 11, nine days before the Chinese attack of October 20, he made an unsuccessful approach to the Government to establish “whether I should launch an attack on the Chinese despite their superiority and the possibility of a reverse”.

…

What conclusion can be drawn from all this? That both sides would in fact have preferred good relations seems clear from the record of Sino/Indian relations up until 1959. US, and perhaps Indian meddling also, in the 1959 uprising clearly pushed relations over a dangerous precipice.

Little of this has been accepted in the West, where China is widely condemned as the aggressive party in the dispute. Explanations for Chinese behaviour range widely. The fact of Chinese withdrawal from the N.E.F.A. following defeat of the Indian forces there has not discouraged those who favour the “expansionist China” explanation.

Others see the Chinese as wanting (a) to drive India into a pro-Western alignment in order to destroy her non-aligned image, despite the fact that a pro-Western Government on China’s southern border means an increased danger to Chinese security, (b) to retard Indian economic growth which was said to be outstripping the Chinese rate of growth, despite the fact it costs China far more than India to maintain troops in the Himalayas and that foreign aid to India has sharply increased since 1962, or (c) to overthrow Nehru’s Government and replace it with a pro-Chinese Government, despite the fact that the 1962 conflict was used as grounds for the imprisonment of the pro-Chinese communist opposition in India.

If one consistent feature emerges from this catalogue of misunderstanding, it is the Western refusal to examine impartially the Chinese case in a dispute involving relations with another country. But that is the subject of another chapter.

REFERENCES

1. Most of the correspondence between the Chinese and Indians from from 1950 onwards has been published in a series of Indian Government White Papers, and it is from this source that many of the quotations etc.., which appear in this chapter have been drawn For background to the territorial dispute, the reader is recommended to Alastair Lamb’s The China-India Border (1964).

2. Letter from Nehru to Chou En-lai of December 52, 1958, recounting conversations held in October 1954.

3. Ibid.

4. George N. Patterson, “Recent Chinese Policies in Tibet and Towards the Himalayan Border States”, The China Quarterly, October December, 1962, and “The Himalayan Frontier”, Survival, September 1963.

5. “The Revolution in Tibet and Nehru’s Philosophy”, Peoples Daily, May 6, 1959.

6. Letter from Nehru to Chou En-lai, September 26, 1959.

7. See The Chinese Threat (1963), Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, New Delhi.

8. Tibet and its History,. op.cit., p. 174.

9. Peking versus Delhi, op.cit., p. 174.

10. See review of Kaul’s book in The Hindu Weekly Review, January 10, 1967.

© 2008 Gregory Clark