Chapter 62 – Post – Bubble

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS and BETWEEN FOUR LANGUAGES:

Post – Bubble

1. Back to Front Land Taxes

2. Living with the Bubble

3. More Japanese Book Writing

4. Campus Life

5. Pride before a Fall

With the Bubble out of the way we could finally begin to clean up some of its excesses.

One of them was the crazy land tax system, imposed allegedly to cure land speculation.

1. Back-to-front Land Taxes

I had long seen the land tax question as crucial, both as an answer to the Bubble and to the problem of local government finances.

Taxes on land-holding were low. They were kept very low if the land was left undeveloped.

An acre of undeveloped hill land might incur an annual tax of only a few hundred yen. That was mainly because the taxes had been set in a much earlier, pre-inflation period, some going back almost to Meiji, and no one wanted to upset anyone by raising them.

Large areas of forested mountain land were virtually untaxable since the owners were untraceable. And no one wanted the land anyway.

(It has been calculated that the amount of land for which ownership cannot be traced, and therefore cannot be developed, is equal to the area of Hokkaido.)

But central government taxes on profits from land sales profits were very high – more than 50 percent in many cases.

Needless to say, this meant there was every incentive to hold on to land, especially if it was left undeveloped, which is what some big land-holders were very happy to do.

And there was very little incentive to sell, which in turn meant it was almost impossible to increase land supply and put a brake on rising prices.

…

But Japanese ‘logic’ said the high land-sales profit taxes were needed as a punishment for speculators cashing in on their ungodly Bubble gains.

It would also discourage them from buying more land (which they did anyway because they had ways to avoid taxes on profits).

My argument was the system should be put into reverse – higher land-holding taxes and lower land-sales taxes (even though higher land holding taxes were not to my advantage at the time).

Higher land-holding taxes were also needed to finance services from local authorities. (Japan’s land taxes were far below the levels that most Western nations saw as normal – less than one percent of market values as opposed to 4-5 percent in many other countries.)

Some years later land-holding taxes were finally lifted, and considerably. But by this time the Bubble was over, and land prices were collapsing.

The high land-holding taxes then did much to discourage the post-Bubble recovery in land prices — a recovery that Japan needed badly in order to stimulate its post-Bubble depressed economy.

…

Especially damaging was a weird Bubble tax on holdings above three acres (3,000 tsubo).

This was supposed to discourage large Bubble-era speculative land purchases, now imposed at precisely the post-Bubble moment when Japan needed to encourage large land purchases, speculative or otherwise, for major development projects.

Around this time I was told by a top Home Affairs (Somusho) official that they had noted my calls for higher land-holding taxes and had finally acted on it.

But that did little to make me happy either. The amount extra I had to pay in taxes for my Boso land had become a heavy burden.

He agreed that the punitive tax on large land purchases was a negative. But by this time the authorities could only look at the revenue as a new source of income.

Bubbles – Not only in Japan

True, Bubble-style irrationality was not exclusive to Japan. We need only to go back to the tulip bubble and the South Seas Islands bubbles of the 18th and 19th centuries for examples.

But Japan’s ability to create its own Bubble, almost out of thin air, and then the seeming inability to realise what was needed to stop it, had been alarming.

Fortunately, falling population has put an end to any future dreams of wild land-price speculation.

But for a while it had been scary.

…

Yet another Japanese post-Bubble contribution to economic theory had come in 2007.

This said taxi fares should rise mainly because post-Bubble demand for taxi rides remained low and liberalisation of the taxi industry meant taxis were in over-supply.

All this had cut income of taxi drivers by some 20 percent. A price increase was needed to make up for their loss of income, we were told.

On this basis starting fares were increased from the already very high 660 yen to 710 yen in 2007.

Western logic would say that if you suffer over-supply and a lack of demand, you should cut fares, not raise them. And some even noted this in Japan.

But no, they were told. Japanese customers would sympathise with the plight of the drivers and continue to use taxis as much as before, even if only to help the drivers.

So Japan as a big familial society has priority over dry economic theory?

2. Living with the Bubble

Meanwhile I had to set about making my own living, separate from the speculative fever around me.

True, I was happy to enjoy some of its side-effects.

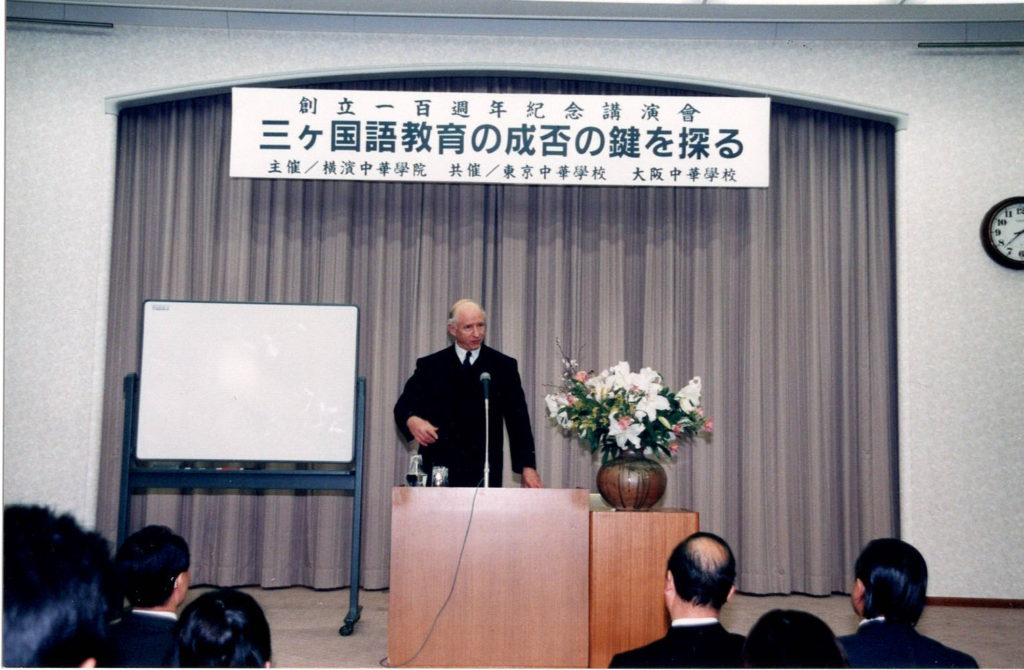

Banks, firms and other organisations flush with cash seemed even more desperate than before to organise lectures and other fiestas. Almost every day saw me heading off to yet another venue.

But less consoling was the feeling of constant tension in the society.

People seemed to know something unusual and unnatural was going on. Many felt uneasy, but helpless to do anything about it.

…

Thanks to the Bubble I learned another new word – jabu jabu.

It was the onomatopoeic rendition of water pouring in and overflowing. It described well the sound of billions of yen bubbling around the economy looking for outlets.

Trying to Get Serious

Often I felt I should try to cut back on the lectures and concentrate more on more serious things, like trying to finish the English language version of my original Tribe book.

I also wanted to take time out master the more educated Japanese I should have been using in my lectures (I was still making do with the language I picked up from conversation and TV broadcasts.)

But the lure of the lecture circuit and other Bubble euphoria was too strong.

It allowed me to join everyone else in the jabu jabu fever – symbolised at the time by a bar in downtown Tokyo, Julianas, where nightly hundreds of sarariman (salarymen) would gather to drink and watch provocatively-dressed ladies dance on a raised platform.

‘Julianas’ became the code-name for that era of Bubble excess.

Its closure was seen as Bubble-finish.

Things Needing Doing

I was beginning to realise that my tribe theory was still rather undeveloped.

Not only did it not explain much about Japan.

It was also requiring me to understand a lot about the rest of the world – the similarities between Japan and Germany, for example.

In effect, if I wanted to explain Japan I would have to explain the rest of the world also.

This in turn gave me the reason further to postpone writing the English-language version of my original book.

3. More Japanese Book Writing

I should have used the same reasoning to avoid writing Japanese-language books.

Kodansha, a leading publisher, had come to me begging me to do a book for them.

In 1978 they had organised for me the slim paperback taidan (dialogue) book – Unique Japanese – which had sold 170,000 copies.

They wanted a follow-up.

I tried to refuse; apart from anything else I had no particular book-length theme to write about. And like most Japanese book-publishers they had forgotten to pay me book royalties.

But they persisted and I assumed they would look after me again as before, regardless of what I produced.

…

I was wrong. This time there was no tape recorder in a luxury hotel room.

There was no editor present to put garbled language into proper Japanese.

I had to write the book in English for translation to Japanese, and then check all the translation mistakes myself.

I had tried to pull together many of the topics I was using on the lecture circuit – Japanese society, the Bubble, foreign policy – into a consistent book theme.

And I had to make endless corrections to the Japanese text since many of the concepts and arguments were new to the translator.

The final version of the book took well over six months to produce.

But Kodansha treated it as a kind of vanity press operation and did little promotion.

The title they gave it was meaningless – Gokai sareru Nihonjin (The Misunderstood Japanese).

They left it mainly to me to push sales at lecture halls – a trick they often used with other lecture circuit speakers I discovered.

All they needed was media exposure and around 10,000 in sales – enough for them to break even with a small profit.

The return to me for all the time and effort was minimal.

…

I should have known; I had had a similar experience a few years earlier: this time with a taidan book for a little-known publisher.

I had agreed to do the book since they had lined up a well-known commentator, Hasegawa Keitaro, as my opposite number.

We were to talk about anything we liked, for a book that was to be entitled Japan – Seen from Inside and Outside.

As with the earlier Kodansha taidan book I assumed that we would just talk into a microphone for a day or so, and they would handle the editing and everything else from there.

But no. They simply ran out the proofs as we had spoken them.

No editorial work was done.

It took me months to clean up the mess – a Japanese-language mess – and this time, again, the publisher’s sales effort had been perfunctory.

Why did they do it, knowing there was no way I or Hasegawa could turn it into a good book by ourselves, without having good editorial assistance?

I think they thought that just having some more names on their book-list would look good.

The irresponsibility of the Japanese book publication industry is another Japanese foible.

4. Campus Life

Meanwhile I was still having to hold down what in theory was a full-time university job. at Sophia (Jochi).

Fortunately my teaching load remained light. I was able to concentrate it into one or two days a week, leaving me time for the lecture curcuit.

I also needed time for handling the articles and interviews I was constantly being asked to contribute to various publications.

A sabbatical year helped.

Even so I was struggling to keep up with demands, especially since weekends, and sometimes more, were having to be devoted to my rather foolish attempt to develop the Boso countryside single-handed.

Fortunately I had kept clear of the various faculty faction fights. But I had let myself get involved in a plan for a faculty shakeup.

I felt we should be divided into two sections – one that retained the existing bias of teaching everything Western-style and in English, and the other to concentrate on Japanese studies with a requirement to learn Japanese properly and use Japanese language sources.

After all, many of our mainly foreign students had come to Japan to learn Japanese and about things Japanese.

The two-section breakup remains, but the attempt to encourage more emphasis on using Japanese as a study tool soon fell apart.

I would have been happy to supervise the Japanese studies sub-section and test out some teaching techniques, but someone else was put in charge.

I decided to concentrate more on my own affairs, based in the well-located office I was renting close to the university campus – an office I needed anyway if I was to have a secretary to handle my various commitments.

(University offices were barely big enough for single individual.)

5. Pride, before a Fall

Book-writing troubles aside, life was good.

During the Bubble, I was in demand as a speaker to explain the Bubble, and how the world saw it.

After the Bubble, I was still in demand to explain the collapse and what Japan should do to recover.

But the happiness was not to last long. Some rather ugly people were at work to make life very unpleasant for me for the next year or two.