Chapter 1 – From Australia to Oxford

BETWEEN FOUR WORLDS: CHINA, RUSSIA, JAPAN AND AUSTRALIA.

BETWEEN FOUR CAREERS and FOUR LANGUAGES

Chapter 1 – From Australia to Oxford

1. The Australian Connection

2. The Santamaria Influence

3. Into Oxford

4. Into Europe

5. A Yugoslavia Connection

My birth certificate says I was born May 19, 1936. It also says I was born in Cambridge, UK. That is because my father, the economist Colin Clark, was working there as an assistant for the well-known economist, John Maynard Keynes.

My father had originally studied chemistry. He switched to statistics, and did much to develop the idea that the size of an economy could be measured by something called GNP. He also came up with the idea that an economy could be sub-divided into the categories of primary, secondary and tertiary industry.

Later he went on to develop the concept of trying to measure economic progress, and the criteria needed for measuring that progress in non-European societies.

Today these things are taken for granted, but people have said that they were revolutionary concepts at the time. His book “Conditions of Economic Progress” was long seen as seminal, in Japan especially where his fame was later to contribute to my Japan career.

Indeed, some still say that he should have received a Nobel Prize for that pioneering work. But others say he did not deserve that honour because later in life his strong Catholic beliefs led him to support rightwing, pro-population expansionist views.

He believed that the world had enough food and other resource potential for such growth, at a time when it was fashionable to say the opposite.

Much of his career was based on challenging the conventional wisdom, and some of his progeny may have inherited the same quality. (For a truly excellent summary of my father’s life, ideas and works, see QEHWPS69 by George Peters in the Queen Elizabeth House Working Paper Series)

…

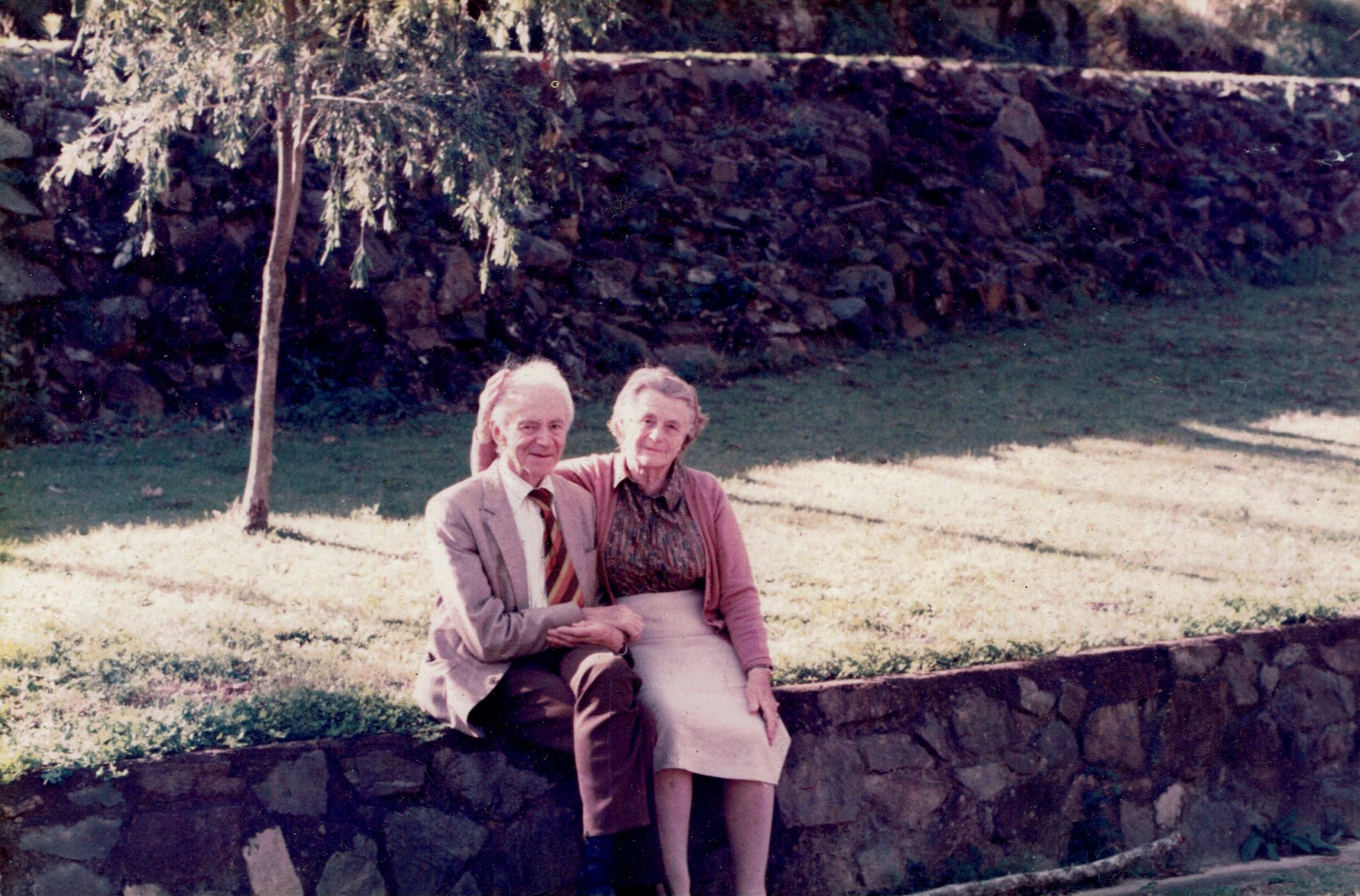

In their younger days both Colin and my mother, Marjorie Tattersall, had been progressives.

She had helped organise a Fabian group at the London School of Economics and Colin had stood, unsuccessfully, as a Labour candidate for a very conservative, rural, East Anglia electorate.

Later both of them moved to rightwing and strongly anti-communist positions. Conversion to Catholicism was one reason. But they also talked about their bitter experiences trying to compete with closed, well-organised pro-communist cliques in various LSE and Fabian faction fights at the time.

1. The Australian Connection

An invitation to be visiting lecturer, first in Western Australia and later at Melbourne University, led Colin to move with his family to Australia in 1938 – a country in which he had long had an interest since his father (my grand-father), had made one of his several fortunes shipping Australian wool to Japan’s Inland Sea in exchange for Japanese textile goods.

My father was also interested in Australia’s pioneering role in electing Labour governments and introducing progressive welfare/wage legislation.

War in Europe persuaded him to stay on in Australia and in 1940 we moved to Brisbane where he had been offered a position as economic adviser, and later Treasury Under-Secretary, to the Hanlon (Labour) government in Queensland – a government which even in his later conservative days he praised for its integrity and good sense.

Ironically, having chosen to stay in Australia to avoid the war in Europe, he soon found himself trapped in a nation at war with Japan, and in one of the few Australian cities to be bombed by the Japanese.

Wartime shortages had made him very sensitive to the need for food and raw materials. Later he would go somewhat overboard in his published predictions that terms of trade would move away from the industrial nations and in favour of resource rich nations like Australia.

But he practiced what he preached, and in 1947 he bought, for 5,000 pounds, a hard-scrabble, ten acre dairy and pig farm on the banks of the Brisbane River at Kenmore, then on the outskirts of Brisbane.

That Kenmore farm changed our lives, considerably. Though only ten years old I already had four younger bothers and with my father often away for conferences in Canberra or abroad, much of the farm work fell on my very immature shoulders.

Mornings I would try to round up some brothers to help me milk our six cows and feed several dozen pigs. To get to school many miles away in central Brisbane we would have to walk or push-bike several miles to the Kenmore bus station – then the focus of a few dusty paddocks and a small, Chinese-owned general store.

(It is now a bustling shopping center).

Weekends were spent roaming the Kenmore hills on horseback, camping trips, rafting the muddy Brisbane river below us, and some fairly futile efforts to grow crops.

2. The Santamaria Influence

By this time my father had developed a close relationship with B.A, Santamaria, the intensely anti-communist Melbourne-based Catholic intellectual who would go on to found the Democratic Labor Party.

I suspect that Santamaria’s famous vision of an Australia where everyone could have ten acres and a pig owed something to my father’s enthusiasm for that Kenmore farm.

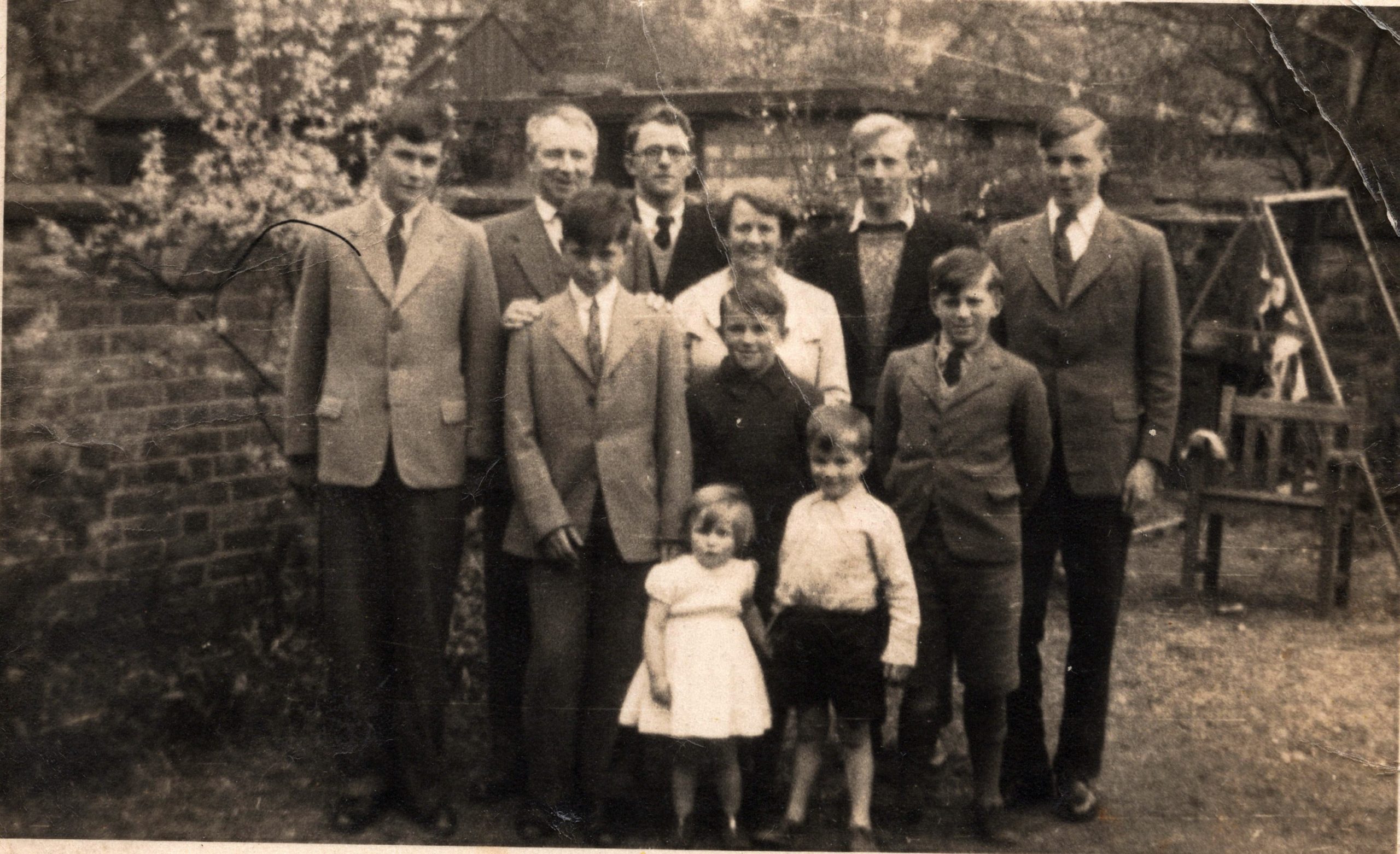

Meanwhile my mother was producing even more brothers. Eventually I was to end up with seven of them, and one sister (she was born in England). The merits of large families was another Santamaria slogan.

am second from right back row

The damage imposed on the healthy development of Australian politics by Santamaria’s DLP is now well known. Later as a diplomat and then as anti-Vietnam War protestor, I was to run head on into the anti-communist vitriol Santamaria had helped impose on Australian foreign policies, in particular the ads and posters showing red arrows from China headed towards Australia.

But for me, in those innocent days, Santamaria was simply a nice, small, dark-complexioned man who used to visit us at Kenmore at times.

…

In 1952 my father accepted the position of head of the Institute of Agricultural Economics at Oxford University.

By this time Queensland was under the rather corrupt Gair government, and I think he was glad to get away despite his deep involvement in Australian affairs at the time.

Though only a very young 16 I was about to graduate high school. This was because twice when changing schools earlier I had been pushed into the class above me, mainly because the class I should have entered was already full.

Many years later in Japan, where 18 was the rigidly fixed age for university entry, I was to be regarded as some kind of prodigy for having finished high school so young. Despite occasional protests from my side, the fiction continued.

High school graduation over, it was assumed I would have to go to the UK to rejoin the family and enter university there. But hemisphere differences meant I still had some months to fill.

So my father arranged for me to work as a two pound a week jackeroo on a Cunnamulla (south-western Queensland) sheep station owned by his close friend and political colleague, the rich pastoralist, Charlie Russell.

It was called Clover Downs, a misnomer if ever there was since the place was semi-desert.

Working 12 hours a day in the mid-summer dust, drafting and marking dozens of up to 50 kilo lambs daily, and then driving 120 miles for weekend booze-ups at the local pub with rough, untutored station hands, was a formative life experience.

3. Into Oxford

Clover Downs behind me and arriving eventually at the family house in Oxford, the future loomed.

Back in Brisbane I had planned to go to Queensland University to study medicine, engineering or ideally, veterinary science (I had always preferred math-science to arts, and the farm had made me interested in animals).

But Oxford in those days emphasised humanities. Its one concession to the outside world of practical affairs was a weak engineering department. The town of Reading some fifty miles away had a veterinary science faculty – too far for someone my age I was told.

Father suddenly decided that I should get a job. He introduced me to the editor of a large Catholic publishing house,The Tablot, that used his material often.

Fortunately in my letter of application I misspelled the chief editor’s name, Byrnes (or was it Burns?). In a polite rejection letter, the editor told me how correct spelling ability was a precondition for publishing work.

My father then suggested Sandhurst, mainly because as a school cadet officer in Brisbane I had won some student platoon efficiency prize. But the Sandhurst idea too fell by the wayside, thankfully. The Vietnam War years were to make me a firm anti-war activist.

Eventually, we settled on my trying to get into my father’s Oxford college, Brasenose. That turned out to be easier than we had expected, mainly because they had favourable quotas for students from former colonies and sons of former alumni.

A brief interview and a simple test of French reading ability saw me accepted. I was still 16, and had to decide what I wanted to study.

First choice was economics, mainly because that was what my father did. It was also a bit closer to the math-science I had liked at school. But my father had strong views about people who had never earned or spent an income trying to grasp abstract economic theories.

He recommended geography as a good preparatory course. I could do economics later if I wanted. I had to agree. Later, I did agree.

…

The next three years passed easily enough – beer and merry-down cider parties, punting on the Isis river, sports (mainly rowing), rushed study for the weekly tutorials.

The first year of college residence, then compulsory for all Oxford students, did little to give me much reverence for Oxford scholasticism. Port wine and class snobbism seemed more the order of the day.

Rowing was somewhat more character forming. I ended up as stroke of the second Brasenose torpid, being chased by Wadham for six agonising days.

The cox for our eight was a diminutive Thai called Patta…..something. For us he was Pat. Years later at a Tokyo conference on the future of Asia, or something, I found myself sitting next to a very fat Thai professor called Patta…or something. Sure enough, it was Pat.

4. Into Europe

For the final two years I lived with the family in our typical four storey, red-brick, central Oxford (Keble Road) terrace house. An older student – Dan Cooper, a cousin of Robert Graves, the poet and writer who lived in Spain – rented the basement.

Unusually for an Oxford student, Dan was married. Later he went on to organise the first mass-transport tours for Brits keen to flaunt their pale bodies and money on the beaches and in the bars of the Spanish Costa Brava.

For me, young and untutored, Dan was to be a very strong influence. He lived boisterously and traveled a lot in Europe.

Thanks to him and his younger brother, Roger, who was then studying Persian and who ended up in a Teheran jail many years later as a British spy, I was to discover a world much more cosmopolitan than I would normally have known as a 17 year old innocent from the colonies.

…

Partly because of Dan’s Robert Graves connection the family decided to take a holiday in Majorca early in 1954. I did most of the driving.

As we left the cold grey winter of England and northern France in the evening, to drive all night down the Rhone valley to reach southern France early the next day, and then drive on through a gloriously warm, early spring Languedoc morning to cross the border into Spain a few hours later, I began to realise the variety and attraction of Europe.

Staying in a rented Majorcan house, with the warm sun shining down on us every day and enjoying the local food and wine, I also realised just how far I was both from cold England with its stodgy food and from Australia with its casual ‘she’ll be right mate’ attitudes to eating (at Clover Downs in the lamb-marking season lunch had often been lamb testicles fried on a sheet of galvanised iron over an open fire). I began to realise there were other lifestyles — a major discovery for a typically close-minded Anglosaxon.

At one of Dan’s frequent basement parties I met Diane, the attractive daughter of a French-Swiss family, part owners of the Chocolat Suchard empire. Like some other European girls at Dan’s parties, she had come to Oxford to improve her English. She was slightly older than I was. We saw a lot of each other during the next two years.

At Oxford in those days, vacations were the main event, not studies. My vacations were usually spent travelling around Europe, either in the family car with other Brasenose students or hitch-hiking with D. who was tri-lingual.

In the process I became addicted to the Teach Yourself books then popular for quick introductions to the various European languages. The idea that one small book could open the door to a totally new and foreign country was, and remains, exciting.

5. A Yugoslavia Connection

The climax to my European adventures was an extraordinary three month stay in Yugoslavia organised by Dan for some of us in the summer of 1956 immediately after our Oxford graduation exams. The then still very communist country was just opening to Western tourism.

The Yugoslav dinar was grossly over-valued. Dan had discovered that we could make a lot of money buying the currency cheaply in Trieste and smuggling it into Croatia to exchange at closer to the official rate with Western tourists at various Adriatic resorts.

It was a dangerous game and I heard later that the next person to try the same caper ended up in a Yugoslav jail for three years.

But we were too young and foolhardy to worry. The former Italian-owned hotels along the Adriatic coastline were good and cheap – the equivalent of one US dollar a day. The food and wine were excellent. We lived like kings.

I was with D. On our currency runs in and out of Trieste we travelled the still unspoiled Slovenian and Croatian countryside on my trusty motorbike, with imported dinars in a plastic bag hidden in the petrol tank.

On a solo trip by train, she was very nearly caught out by an amorous ticket collector. She had hidden the currency around her waist.

A boat trip down the Adriatic coast and a weekend together in the old port town of Dubrovnik were high notes. We also made a bit of money.

But this time the Teach Yourself books had not been as useful earlier with German, Italian or Spanish. You do not learn SerboCroat overnight. But the trip had given me a strong interest in Slav culture and people. That interest was to influence my career in some very unexpected ways.

…

But with the autumn the tourists disappeared.

We headed back north – D. to become a tutor in a remote Austrian mountain lodge; me to England and a new career.